On the pulse: cutting edge research on the power of social touch

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Die Kraft der Berührung: Eine neue Grenze für psychologische Interventionen

In den letzten Jahren hat das Konzept der „Berührungsmedizin“ in der medizinischen und psychologischen Fachwelt große Aufmerksamkeit erlangt. Dieser neue und innovative Ansatz, der das therapeutische Potenzial der Berührung hervorhebt, ist besonders im Bereich der Psychologie von Bedeutung, wo alles andere als traditionelle Interventionen zu kurz greifen können. Ein kürzlich in Frontiers in Psychiatry veröffentlichter Artikel von Müller-Oerlinghausen und Kollegen (2024) befasst sich mit der Rolle der Berührungsmedizin als vielversprechende Interventionsmethode zur Behandlung affektiver Störungen wie Depressionen.

Die wissenschaftliche Grundlage für die Berührungsmedizin liegt in dem Verständnis, wie Berührung sowohl das Gehirn als auch den Körper beeinflusst. Von zentraler Bedeutung ist dabei die Entdeckung der C-taktilen Afferenzen, spezialisierter Nervenfasern, die auf sanfte, streichelnde Berührung reagieren. Diese Fasern spielen eine entscheidende Rolle bei der Emotionsregulierung und fördern Gefühle von Ruhe und Sicherheit. Wenn sie aktiviert werden, regen sie die Ausschüttung von Oxytocin an, das oft als „Liebeshormon“ bezeichnet wird und die soziale Bindung fördert und Stress abbaut. Darüber hinaus senkt Berührung den Cortisolspiegel, das wichtigste Stresshormon des Körpers, und hilft so, Angstzustände und depressive Symptome zu lindern.

Müller-Oerlinghausens Arbeit legt den Schwerpunkt auf die Anwendung der Berührungsmedizin bei der Behandlung von Depressionen, einer Erkrankung, von der weltweit Millionen Menschen betroffen sind. Depressionen führen häufig dazu, dass sich die Betroffenen isoliert und abgekoppelt fühlen, sowohl von anderen als auch von ihrem eigenen Körper. Durch die Integration von Berührungen in therapeutische Maßnahmen können Kliniker dazu beitragen, diese Kluft zu überbrücken und den Patienten ein Gefühl der Verbundenheit und des Trostes zu vermitteln. Die Berührungstherapie kann herkömmliche verbale Therapien ergänzen, insbesondere bei Patienten, denen es schwerfällt, ihre Gefühle verbal auszudrücken, oder die auf herkömmliche Behandlungen nicht vollständig ansprechen.

Über Depressionen hinaus zeigt die Berührungsmedizin vielversprechende Ergebnisse bei der Behandlung anderer psychologischer Erkrankungen. Bei Patienten mit Angststörungen beispielsweise kann die beruhigende Wirkung von Berührungen dazu beitragen, die Übererregung zu reduzieren und die Entspannung zu fördern. Auch bei Menschen mit PTBS, die aufgrund eines Traumas eine erhöhte Empfindlichkeit gegenüber Berührungen aufweisen, kann eine sorgfältig durchgeführte Berührungstherapie dazu beitragen, eine positive Verbindung zu ihrem Körper wiederherzustellen und so die Traumaheilung zu erleichtern.

Die Umsetzung von berührungsbasierten Interventionen im klinischen Umfeld erfordert jedoch sorgfältige Überlegungen. Ethische Bedenken, insbesondere in Bezug auf die Einwilligung und die Wahrung der beruflichen Grenzen, stehen dabei im Vordergrund. Therapeuten müssen darin geschult werden, mit diesen Herausforderungen umzugehen und sicherzustellen, dass Berührungen auf eine Weise eingesetzt werden, die sowohl effektiv als auch respektvoll gegenüber dem Patienten ist.

Wie die Forschung von Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. (2024) nahelegt, stellt die Berührungsmedizin eine wertvolle Ergänzung des therapeutischen Instrumentariums der Psychologie dar. Indem sie sich die Kraft der Berührung zunutze machen, können Kliniker einen ganzheitlicheren und körperbetonten Ansatz für die psychische Gesundheitspflege anbieten und den Patienten neue Wege zur Heilung und zum emotionalen Wohlbefinden eröffnen.

Weitere Informationen über die heilende Kraft der Berührung finden Sie in einem kürzlich erschienenen Artikel und in einem Video mit Prof. Merle Fairhurst, die darüber spricht, wie digitale Berührungstechnologien für Gesundheit und Wohlbefinden genutzt werden können.

Adoleszenz: wenn sich alles ändert

Körperlicher Kontakt ist entscheidend für die frühe körperliche, kognitive und emotionale Entwicklung, und wir wissen heute, dass er auch für das lebenslange psychische Wohlbefinden wichtig ist. Schon früh im Leben zeigen Kleinkinder ein grundlegendes Bedürfnis nach Nähe zu ihren Eltern und Bezugspersonen. Affektive Berührungen können nicht nur die sozialen Fähigkeiten, sondern auch das Lernen und die kognitiven Fähigkeiten im Allgemeinen verbessern. Mit dem Heranwachsen folgt diese Affinität zur Berührung geschlechtsspezifischen, kulturellen, ideologischen und ethischen sozialen Normen. Diese Normen beeinflussen, wie zwischenmenschliche Berührungen eingesetzt werden, wann sie als angenehm empfunden werden und wie Berührungen eingesetzt werden, um unsere Beziehungen zu anderen zu erleichtern.

Die Adoleszenz ist ein sensibler Zeitraum für die körperliche und neurophysiologische Entwicklung eines Menschen: Alles verändert sich und organisiert sich neu, und es kann schwierig sein, Bindungen zu anderen aufzubauen. Die Rolle der Berührung im persönlichen und sozialen Leben ist etwas, worüber Kinder und Jugendliche in diesem Alter vielleicht noch nicht nachdenken oder sprechen, aber ein besseres Verständnis dieses grundlegenden Mittels der sozialen Verbindung und Kommunikation kann ihr psychophysisches und soziales Wohlbefinden fördern.

Wir haben eine Zusammenarbeit mit der Leipzig International School begonnen, um herauszufinden, wie Heranwachsende Berührungen im Alltag erleben, um ihnen zusätzliche Hilfsmittel an die Hand zu geben, mit denen sie sich selbst besser verstehen können, und um einen Beitrag zum kollektiven Wissen über die Rolle von Berührungen im Jugendalter zu leisten.

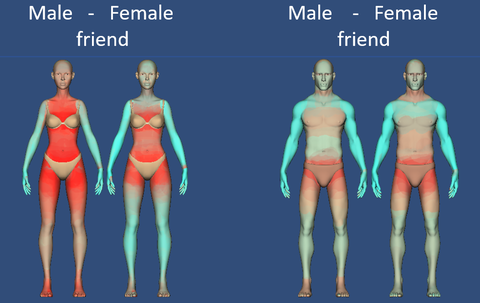

Mit Hilfe der HandsOn-App baten wir die SchülerInnen, verschiedene Übungen auszuprobieren, um zu verstehen, wann, von wem und wo es am angenehmsten ist, berührt zu werden. Sie malten Heatmaps von Ganzkörper-Avataren, die die Körperzonen anzeigten, die sie als angenehm/unangenehm empfinden, wenn sie von Familie oder Freunden, einem weiblichen oder männlichen Freund berührt werden. Wir untersuchten auch, inwieweit ihre Beziehung zu Berührungen mit ihrem Bewusstsein für die körperlichen Reaktionen auf Emotionen und mit der Menge und Qualität der Unterstützung zusammenhängt, die sie in ihrem sozialen Netzwerk wahrnehmen. Zu diesem Zweck beantworteten die Schüler eine Reihe von Umfragen über ihre Beziehungen zu Gleichaltrigen und Familienmitgliedern.

Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass soziale Berührungen von Familienmitgliedern insgesamt angenehmer empfunden werden als von Freunden und dass soziale (z. B. Hände und Arme) im Vergleich zu intimen Körperzonen (z. B. Torso und Oberschenkel) als angenehmer empfunden werden. Bemerkenswert ist, dass Mädchen und Jungen unterschiedliche Tendenzen bei der Einstellung zu Berührungen durch Freunde zeigen. Während männliche Jugendliche im Vergleich zu jüngeren Kindern ein erhöhtes Verlangen nach sozialen Berührungen zeigen, berichten weibliche Jugendliche über eine erhöhte Abneigung gegen Berührungen, insbesondere an intimen Körperzonen und von männlichen Freunden. Schülerinnen und Schüler, die soziale Berührungen in höherem Maße mögen, zeigen auch ein höheres Bewusstsein für die körperlichen Korrelate von Emotionen und berichten, dass sie auf stärkere Unterstützung durch ihr soziales Netzwerk angewiesen sind.

Unsere Ergebnisse unterstreichen den nuancierten Charakter sozialer Berührungserfahrungen unter Jugendlichen und beleuchten deren subjektive Natur und unterschiedliche Präferenzen, die von Faktoren wie Geschlecht, Alter und Beziehungsdynamik abhängen. Diese Ergebnisse tragen nicht nur zu unserem Verständnis von zwischenmenschlichen Berührungen bei, sondern haben auch bedeutende Auswirkungen auf Bildung und Gesundheit. In Bildungseinrichtungen kann die Anerkennung und Respektierung individueller Präferenzen für soziale Berührungen ein integrativeres und unterstützenderes Umfeld fördern. Im Bereich der Gesundheit und Prävention können zwischenmenschliche Berührungen als Katalysator für ein gesteigertes Selbst- und Körperbewusstsein sowie als wirksames Instrument zur Erkennung und Bewältigung von Emotionen dienen. Letztendlich kann dies die sozialen und emotionalen Kompetenzen und das Lernen der Jugendlichen fördern und eine entscheidende Rolle beim Aufbau gesunder Beziehungen spielen.

Können Sie einem Roboter vertrauen?

Abgesehen von unseren alltäglichen Interaktionen mit Alexa, Siri und Rumba werden humanoide Roboter für reichere Formen der sozialen Interaktion (oder sollten wir sagen Beziehung?) mit Menschen entwickelt. Wir haben versucht, sie dazu zu bringen, sich so menschlich wie möglich zu bewegen, zu sprechen und Mimik zu zeigen. Damit wollen wir erreichen, dass diese Roboter als vertrauenswürdig wahrgenommen werden. Aber die Frage, die wir uns stellen wollen, lautet: Wenn Technik und Informatik den perfekten humanoiden Roboter erschaffen, wird das ausreichen, um das Vertrauen der Menschen zu wecken? Per Definition beruht Vertrauen auf der Bereitschaft, sich auf eine andere Partei zu verlassen, um Ziele zu erreichen, die wir allein nicht erreichen könnten. Wichtig ist, dass wir jemandem nicht nur aufgrund seiner funktionalen Fähigkeiten vertrauen, sondern auch aufgrund persönlicher Eigenschaften wie Ehrlichkeit und Wohlwollen. Wir können sagen, dass Vertrauen einen Zustand der Verwundbarkeit impliziert, in dem ich das Risiko eingehe, mich in die fähigen, fürsorglichen Hände einer anderen Person zu begeben.

Angenommen, die Hände des Roboters sind fähig, können sie dann auch fürsorglich sein? Fürsorge und Mitgefühl beruhen auf Empathie, d. h. der Fähigkeit, sich in die Lage des anderen hineinzuversetzen und seine Gefühlslage zu teilen. Empathie ist wie ein Spiegel: Sie gibt beiden Partnern die Möglichkeit zu fühlen, was der andere fühlt. Um einem Roboter zu vertrauen und seine Verletzlichkeit zu teilen, brauchen wir also vielleicht keinen perfekten Roboter, sondern den Funken der Unsicherheit und Verletzlichkeit, der Menschen beseelt. Daraus ergibt sich die Frage: Können wir Robotern Verletzlichkeit verleihen? Können sie gleichzeitig fähig und verletzlich sein?

Einer der intimsten Kanäle zur Verbindung mit dem anderen, zum Austausch von Gefühlszuständen, Verletzlichkeit und gegenseitigem Vertrauen ist die soziale Berührung: ein statischer Druck oder ein sanftes Streicheln am Arm des anderen, Umarmungen, Händeschütteln, Kitzeln, Liebkosungen. Hier am CeTI (https://ceti.one/de/) untersuchen Juniorprofessorin Merle Fairhurst und ihr Team die Macht dieser Art von Berührung (gegeben, empfangen, gegenseitig) bei der Kommunikation verschiedener Bedeutungen und Emotionen, um zu trösten oder Trost zu suchen, um Freude zu teilen. Wir fragen uns, ob diese Erfahrung auch bei Mensch-Roboter-Interaktionen möglich ist.

„Um ein sozial intelligenter Akteur zu werden, muss ein Roboter in der Lage sein, menschliche Berührungen wahrzunehmen, zu klassifizieren und zu interpretieren und darauf angemessen zu reagieren“, sagt Dr. Merel Jung, die an dem Projekt von der Universität Tilburg mitarbeitet. Aber selbst wenn dies technisch möglich wäre, wie würde es von den Menschen erlebt werden? Würden das menschliche Gehirn und die physiologischen Systeme so reagieren wie bei einer Berührung von Mensch zu Mensch oder auf eine ganz andere Weise?

Möchten Sie mehr darüber erfahren? Hier finden Sie unsere Forschungsergebnisse zum Thema Berührung und Vertrauen.

Verletzliche Roboter? Eine Debatte zwischen Psychologie und Technologie

Eines der Merkmale der Interaktion mit Menschen im Gegensatz zu unbelebten Objekten ist die Unsicherheit. Der kommunikative Austausch ist ein Kreislauf aus Erwartungen, Vorhersagefehlern und der Aktualisierung des gegenseitigen Wissens. Diese Ungewissheit macht beide Partner verletzlich, und vielleicht gerade deshalb menschlich. Ist diese Verletzlichkeit notwendig, um einen Roboter als Sozialpartner zu betrachten? Wie können wir, technisch gesehen, eine Maschine mit Ungewissheit und Verletzlichkeit beleben? Das scheint das Gegenteil von dem zu sein, was die Technik zu erreichen versucht.

Dieser Beitrag versammelt die Fragen und Antworten eines Interviews zu diesem Thema mit Dr. Merel Jung, Forscherin an der Abteilung für Kognitionswissenschaften und künstliche Intelligenz an der Universität Tilburg, Niederlande. Mit einem Hintergrund in Psychologie und einer Leidenschaft für Multidisziplinarität arbeitet Dr. Jung an sozialer künstlicher Intelligenz, die es Robotern ermöglichen soll, natürlicher mit Menschen zu interagieren, wobei der Schwerpunkt auf der Berührungsmodalität als Mittel der sozialen Kommunikation liegt.

F. Als Experte für die psychologischen Prozesse, die der Interaktion zwischen Mensch und Roboter zugrunde liegen, was sind die grundlegenden Merkmale eines Roboters, dem wir soziale Eigenschaften zuschreiben, mit dem wir nicht nur interagieren können, um Dinge zu tun, sondern auch, um zu kommunizieren und eine Beziehung aufzubauen?

A: Es scheint, dass die Menschen nicht viel brauchen, um Objekte, Roboter oder Tiere zu vermenschlichen. Als ich als Gastwissenschaftler an der University of British Columbia in Kanada tätig war, habe ich an der Entwicklung und Erprobung von affektiven Robotern namens CuddleBits mitgewirkt. Bei diesen Roboterwesen handelte es sich um Kugeln mit nur einem Freiheitsgrad: Sie konnten sich nur auf und ab bewegen, um das Atemverhalten zu simulieren und verschiedene Emotionen zu vermitteln. Die Menschen stellten sich diese Kreaturen spontan als ihre Haustiere vor, auch wenn sie keinem bestimmten Tier ähnelten. Das gilt auch für die Geräusche: Wenn die Menschen die Kreatur als Katze wahrnahmen, wurden ihre motorisierten Geräusche als Schnurren interpretiert. Diese Studien scheinen darauf hinzuweisen, dass schon einfache Bewegungen ausreichen können, um einer Maschine soziale Eigenschaften zuzuschreiben. In einer anderen Studie, an der ich beteiligt war, wurden Gesundheitsdienstleister über den Einsatz eines Robbenroboters für Menschen mit Demenz befragt. Die Pfleger berichteten, dass der Robbenroboter Erinnerungen an frühere Haustiere wachrufen kann, auch wenn es eher ungewohnt ist, eine Robbe auf dem Schoß zu halten. Die Vorstellungskraft des menschlichen Geistes ist sehr reichhaltig und mächtig.

F: Inwieweit ist dies ein Neuheitseffekt? Wenn ich zum ersten Mal mit etwas Neuem interagiere, neige ich vielleicht dazu, mich auf mein Vorwissen zu stützen, um gewisse Erwartungen aufzubauen und zu interpretieren, was vor sich geht. Aber auf lange Sicht brauchen wir vielleicht mehr menschenähnliche Eigenschaften, um sie als soziale Akteure wahrzunehmen?

A: Das hat mit dem Konzept der Ungewissheit zu tun, das Interaktionen mit anderen Menschen und Tieren interessant macht, da man nie weiß, was sie tun werden. Wenn man einen Roboter mit vorprogrammierten Verhaltensweisen und Interaktionsschemata hat, wird man dessen irgendwann überdrüssig. Diese begrenzte Form der Interaktion kann für kleine Kinder oder Menschen mit kognitiven Beeinträchtigungen, für die ein paar schöne taktile Erfahrungen sehr anregend sein können, sehr effektiv sein. Da die Forscher versuchen, Roboter zu programmieren, die langfristig interessant sein können, bewegen sich einige in Richtung generativer Algorithmen, die über rein vorprogrammierte Verhaltensweisen hinausgehen und stattdessen von einigen handgefertigten Schemata ausgehen und dann mithilfe tiefer neuronaler Netze neue generieren. Dies könnte ein Weg sein, um Unvorhersehbarkeit und Flexibilität in das Verhalten von Robotern einzubauen, ohne dass umfangreiche Programmierarbeit geleistet werden muss, bei der jedes Verhalten von Grund auf spezifiziert und implementiert werden muss. Eine Herausforderung wäre es, diese Verhaltensweisen erkennbar, plausibel und sinnvoll zu machen: Es geht nicht um zufällige Verhaltensweisen, sondern um die Kommunikation zwischen Mensch und Roboter, die einander verstehen und sich aneinander anpassen. Diese Forschung befindet sich noch in einer sehr frühen Phase, in der die Forscher versuchen, handgefertigte und generierte Verhaltensweisen zu vergleichen, die zum Beispiel mit bestimmten Emotionen verbunden sind, um zu sehen, ob sie ähnlich sind und Menschen sie tatsächlich erkennen können.

Eine weitere interessante Perspektive ist die Nachahmung von Verhaltensweisen zwischen Menschen und Robotern. Wenn Menschen miteinander interagieren, gleichen sie sich an, verwenden allmählich die gleichen Worte, Körperhaltungen und Gesichtsausdrücke und teilen sich Rückkanalhinweise. Wenn ich spreche und Sie nicken, weiß ich, dass Sie wahrscheinlich zuhören und verstehen, was ich sage. Wenn der Roboter stillsteht, während ich spreche, frage ich mich vielleicht, ob er noch funktioniert oder nicht. All diese kleinen nonverbalen Hinweise sind wichtig und können entscheidend sein, um mit Robotern als Sozialpartner umzugehen. Eine Vorgeschichte zu haben, ist ebenfalls von entscheidender Bedeutung: Wenn bei einer wiederholten Interaktion zwischen einem Roboter und einem Menschen der Roboter so reagiert, als wäre es immer die erste Begegnung, würde dies die Beziehung zerstören. Es wäre interessant, die Fähigkeiten von Robotern zur Personalisierung der Interaktion zu erweitern. Zum Beispiel mit Technologien zum Scannen von Gesichtern, bei denen ein Roboter erkennt, wer vor ihm steht, und Verhaltensweisen an den Tag legt, die spezifisch für diese Person sind und auf früheren Erfahrungen aufbauen.

F: Stellen wir uns vor, wir könnten Robotern etwas von der Verletzlichkeit geben, die Menschen zu Menschen macht. Wenn ein Roboter etwas nicht könnte und seine Grenzen offenlegte, wären wir dann frustriert (bei einer Fehlfunktion) oder mitfühlend?

A: Manchmal erwarten die Leute einwandfreie Maschinen. Andererseits wissen wir, dass das nicht der Fall ist. Wir wissen, dass wir bei der Verwendung eines Navigationssystems trotzdem aufpassen müssen, denn es kann blinde Flecken geben, die es nicht abdeckt. Es besteht die falsche Vorstellung, dass KIs nicht voreingenommen sind, obwohl sie auf Daten basieren und die Daten wahrscheinlich voreingenommen sind, weil sie von Menschen gesammelt werden. Zurück zu den Robotern: Es kann von den Erwartungen der Benutzer abhängen. Wenn ein Roboter wie ein Haustier aussieht, erwarten sie vielleicht nicht, dass er ein Gespräch führt. Letztendlich ist es eine Frage der Affordanzen: Wenn ein Roboter Beine hat, erwarten Sie, dass er laufen kann. Wenn er das nicht sehr reibungslos und präzise tut, kann dies seine Glaubwürdigkeit mindern. Andererseits kann ein kleiner humanoider Roboter, der unbeholfen läuft und verletzlich wirkt, als Kleinkind wahrgenommen werden und Empathie bei den Benutzern hervorrufen.

Aber im Moment wenden wir menschliche soziale Normen auf Roboter an und diskutieren, was wir von anderen mit bestimmten Eigenschaften erwarten und wie wir mit ihnen interagieren. Vielleicht müssen wir irgendwann neue soziale Normen schaffen, um die Mensch-Roboter-Interaktion gezielter zu steuern. Beispielsweise benötigen wir möglicherweise neue ethische Prinzipien, um zu bestimmen, welche Arten der Berührung bei der Interaktion mit einem Roboter angemessen sind. Wie würden wir einen Roboter begrüßen? Mit einer Umarmung oder einem Händedruck? Kann der Roboter die Initiative ergreifen und eine Person an der Schulter berühren oder kann er nur auf menschliche Initiativen reagieren?

Sie möchten mehr erfahren? Hier sind einige interessante Artikel zu diesem Thema.

- Suguitan, M., Bretan, M., & Hoffman, G. (2019, March). Affective robot movement generation using cyclegans. In 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) (pp. 534-535). IEEE.

- Suguitan, M., Gomez, R., & Hoffman, G. (2020, March). MoveAE: modifying affective robot movements using classifying variational autoencoders. In 2020 15th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) (pp. 481-489). IEEE. Link for video demonstration: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3371382.3378202

- Bucci, P., Cang, X. L., Valair, A., Marino, D., Tseng, L., Jung, M., ... & MacLean, K. E. (2017, May). Sketching cuddlebits: coupled prototyping of body and behaviour for an affective robot pet. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 3681-3692). Link for videos: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3025453.3025774

- Jung, M. M., Van der Leij, L., & Kelders, S. M. (2017). An exploration of the benefits of an animallike robot companion with more advanced touch interaction capabilities for dementia care. Frontiers in ICT, 4, 16.

- Jung, M. M., Poel, M., Poppe, R., & Heylen, D. K. (2017). Automatic recognition of touch gestures in the corpus of social touch. Journal on multimodal user interfaces, 11, 81-96.