Jan 21, 2026

Sweet signals: tracking crucial cell messengers for the first time

Ben Schumann (right) and his former lab at the Crick. He is now Professor of Biochemistry at TUD Dresden University of Technology.

Biochemist Benjamin Schumann and his team have succeeded for the first time in analysing and tracking complex sugar-protein structures in the body. These so-called proteoglycans help cells to sense external signals, control their growth and respond to their environment. The newly developed method could enable new approaches to tumour research in the future. The study was published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

A cell's most important conversations happen at its surface, the interface where biological messages are received and responded to. Controlling which signals get through, and how loudly they are heard, are sugar-coated sensors called proteoglycans.

Composed of a core protein and long sugar chains, these big signalling molecules sit on the cell surface or are deposited into the space surrounding cells. Despite proteoglycans’ clear importance, their unique structure means they are hard to analyse using traditional methods. Prof. Ben Schumann, now Chair of Biochemistry at TUD Dresden University of Technology, endeavoured to change this.

During his time at the Francis Crick Institute in London, he and his team searched for a novel solution: “Proteoglycans are vital for the growth of most of our organs - alterations in these molecules are lethal in developing embryos," he describes. “Although studies have identified just about a hundred in human cells, there are likely many more. At the moment, it’s a clunky process to identify just one proteoglycan at a time, work out its structure and what it’s doing. I wanted to try and streamline this.”

Ben’s team at the Crick and Imperial College, led by Zhen Li and Himanshi Chawla, worked out a method to characterise and track proteoglycans using ‘click chemistry’, which involves joining molecules together permanently.

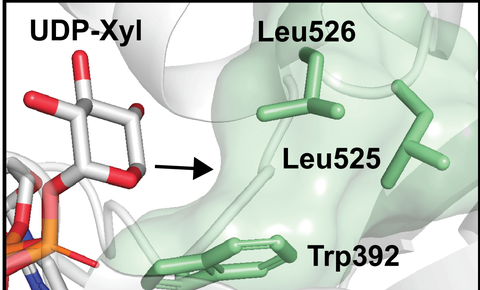

Illustration shows the enzyme being engineered, replacing the amino acid Leu526 with a smaller amino acid. This allows it to accept a modified sugar.

“Instead of focusing on the whole proteoglycan molecule, we targeted one of the steps in making it,” explains Himanshi. “Using the ‘bump and hole engineering technique, where we modify a ‘hole’ in an enzyme and a ‘bump’ in a sugar, we altered the enzyme that glues together a sugar and protein to form the proteoglycan, so that it would accept a bumped version of the sugar.”

Crucially, this modified sugar contains a chemical tag which means it can be traced by using click chemistry. For instance, scientists can attach a fluorescent molecule to ‘see’ the molecule by imaging, or a molecule acting like an anchor to isolate and further study it. The enzyme adds the modified sugar to the protein, creating a tagged proteoglycan whose behaviour can now be studied.

“This technique allowed us to fill in the blanks,” says Zhen. “The modified enzyme and sugar were successfully incorporated into normal mammalian cellular processes, showing that the technique doesn’t alter their biology.”

Now that proteoglycans can be tracked more easily, Ben sees a world of opportunity. “Researchers could tag these molecules in different contexts to see what they’re doing, such as in organ development,” he says. “We could also alter proteoglycan function by replacing the sugar chain with a different biological or synthetic molecule in what I’m thinking of as ‘designer proteoglycans’.”

Ben is now taking this chemical toolkit with him to TUD Dresden University of Technology in Germany, where he plans to investigate how proteoglycans help tissues develop into complex organs.

He also believes the technique holds promise for fighting tumours. “I’m hopeful this tracking system could help us understand and even modify what signals a cancer cell is picking up, perhaps by introducing a designer proteoglycan that can’t respond to usual cancer growth drivers,” says Ben. “This might one day help us find better treatments.”

Read the full article of the Crick Institute: https://www.crick.ac.uk/news/2026-01-19_sweet-signals-tracking-crucial-cell-messengers-for-the-first-time

Ben’s work was majorly funded by the Biotechnological and Biological Sciences Research Council UK.

Original Publication:

Li, Z., Chawla, H., Di Vagno, L. et al. Xylosyltransferase engineering to manipulate proteoglycans in mammalian cells. Nat Chem Biol (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41589-025-02113-w

Contact:

Benjamin Schumann

Chair of Biochemistry

TUD

Tel. +49 351 463-34494

Email: