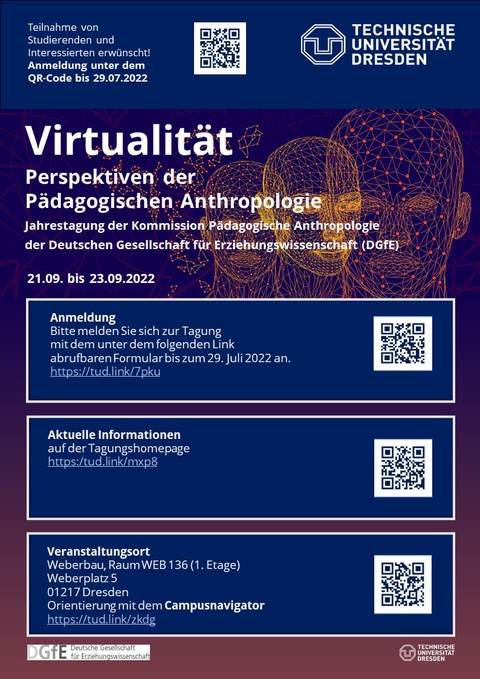

Tagung "Virtualität - Perspektiven der Pädagogischen Anthropologie"

Jahrestagung der Kommission Pädagogische Anthropologie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft, 21. bis 23. September 2022

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Call for Papers

Bei näherer Betrachtung der Begriffsverwendung von ‚Virtualität‘ eröffnet sich ein Feld heterogener Sichtweisen auf das damit bezeichnete Phänomen, das durch eine „nachgerade heillose Verwirrung des Begriffes“ zu charakterisieren ist (vgl. Kasprowicz/Rieger 2020a, S. 10). Insbesondere im Kontext der Digitalisierung lässt sich seit den 1980er und 1990er Jahren eine Polarisierung der Debatte konstatieren, bei der einerseits die grenzüberschreitenden Möglichkeiten digitalisierter (‚virtueller‘) Realitäten verklärt und andererseits die Effekte der Verlusterfahrungen menschlichen Realitätsbezugs im Schein (‚virtualisierter‘) künstlicher Welten beklagt werden (vgl. Völcker 2010, S. 10ff., 316f.).

Mit der sich hier abzeichnenden, wechselseitig ausschließenden Gegenüberstellung von Realität und Virtualität ist eine Verkürzung des Phänomens der Virtualität verbunden und damit zugleich eine Simplifizierung der Beschreibung menschlichen Weltbezugs, die dem komplexen Verhältnis von Virtualität und Lebenswelt nicht gerecht wird. Im Anschluss an diesen Diskurs lässt sich in der Auseinandersetzung mit der Bedeutung der Virtualität für die menschliche Weltaneignung und -gestaltung auch unter Rückbezug auf die historische Semantik des Begriffs in der vordigitalen Zeit (vgl. Roth 2000; Knebel 2001; Völcker 2010) und mit Blick auf die aktuell weitreichenden lebensweltlichen Auswirkungen die Abgrenzung der Virtualität von der Realität infrage stellen (vgl. Grimshaw 2014; Kasprowicz/Rieger 2020a; Rieger/Schäfer/Tuschling 2021).

Die Kritik an der Verkürzung des Problems führt zu vielfältigen Versuchen der Beschreibung, deren Spektrum sich durch die Relationierung zu verschiedenen korrespondierenden Begriffen wie Möglichkeit, Vermögen, Potentialität, Aktualität, Imagination, Simulation, Fiktion, Schein, Digitalität, Medialität, Immersion u.a. skizzieren lässt. Hierbei wird zu diskutieren sein, inwieweit Virtualität, ausgehend vom „Entwurfscharakter des menschlichen Seins“ (Rieger 2014, S. 25), als „universale Voraussetzung eines jeglichen Weltbezugs“ zu charakterisieren ist und in welchem Umfang sie als Bedingung menschlicher Wahrnehmung und Aneignung von Welt neue Perspektiven auf „all das [eröffnen kann], was sich im Modus des Als ob vollzieht“ (Kasprowicz/Rieger 2020a, S. 5f.). In diesem Sinne soll daran erinnert werden, dass sich der Begriff einerseits vom Lateinischen virtualis ableiten lässt, mit dem das Mögliche, etwa als eine mögliche Wirklichkeit oder auch künstliche Realität, in Verbindung steht; andererseits aber auch vom lat. virtus herkommt, womit etwa Kraft, Vermögen, Tugend, Tüchtigkeit bezeichnet werden.

Für die Erziehungswissenschaft stellt sich grundsätzlich die Frage einer „virtuellen Pädagogik“ (Beiler/Sanders 2020), die sich jedoch nicht auf die Optimierung der Verwendung digitaler Medien im Unterricht oder das Lernen in digitalisierten Lernumgebungen bzw. ‚virtuellen‘ Realitäten reduzieren lässt (vgl. ebd., S. 502). Vielmehr gilt es, Virtualität als Herausforderung für pädagogisches Handeln im Kontext entsprechender gesellschaftlicher Transformationsprozesse zu betrachten, die im Rücken der Virtualisierung von Lebenswelten machtvolle und gewaltförmige Effekte zeitigen (vgl. Levy 1997; Sprenger 2020, S. 107).

Für die Tagung eröffnet sich eine Vielzahl an thematischen Möglichkeiten.

Neben der grundsätzlichen Reflexion über das Verhältnis Mensch und Virtualität (homo virtualis, digitalis, fictionalis, medialis, utopicus etc.) könnte in einem ersten grundlagentheoretischen Zugang die Bedeutung von Virtualität für die Beschreibung pädagogisch-anthropologischer Dimensionen und Prozesse diskutiert werden. Denkbar wäre z.B. die Betrachtung von Bildung und Erziehung, Lernen, Bildsamkeit sowie Subjektivierung, Autonomie, Information und Wissen, desgleichen von Körperlichkeit, Vulnerabilität, Gewalt, Mimesis, (Sozial‑)Raum, Ritual, Imagination, Mythos, Kunst und Spiel – ggf. auch unter Berücksichtigung der historischen Semantik.

Zudem wäre es in einem zweiten Schritt möglich, Virtualität als Bedingung menschlicher Weltaneignung in verschiedenen pädagogischen Feldern zu untersuchen und pädagogische Konzepte und Praktiken auf ihre pädagogisch-anthropologischen Implikationen im Kontext von Virtualität zu befragen. Neben Thematisierungen der medialen und technologischen Umbrüche in der Folge der ‚Computerisierung‘ sind ebenfalls Untersuchungen zu ‚virtuellen Räumen‘ der vordigitalen Zeit möglich (vgl. Adams 2014). Hier stellt sich überdies die Frage nach den methodologischen Anschlüssen solcher Untersuchungen. Quer zu den skizzierten thematischen Einsätzen liegt die nicht zu vernachlässigende Berücksichtigung gesellschaftlicher, epistemologischer, ethischer sowie technologischer Voraussetzungen und Konsequenzen von Virtualität (etwa in Bezug auf Verbildlichung, Datafizierung, Vernetzung, fake news).

Bitte senden Sie Ihre Vortragsvorschläge mit maximal 2500 Zeichen (incl. Leerzeichen, excl. Literatur) bis zum 29. April 2022 per E-Mail an Prof. Dr. Carsten Heinze (allgemeine.erziehungswissenschaft @tu-dresden.de).

Die Informationen zur Tagung und das Programm werden im Mai 2022 versendet.

Literatur

Adams, P. C. (2014): Communication in Virtual Worlds. In: Grimshaw, M. (Hg.): The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality. Oxford u.a.: Oxford University Press, S. 239-253.

Beiler, F./Sanders, O. (2020): Virtuelle Pädagogik. In: Kasprowicz, D. / Rieger S. (Hg.): Handbuch Virtualität. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, S. 501-519.

Grimshaw, M. (Hg.) (2014): The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality. Oxford u.a.: Oxford University Press.

Kasprowicz, D./Rieger, S. (2020a): Einleitung. In: Dies. (Hg.): Handbuch Virtualität. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, S. 1‑22.

Kasprowicz, D./Rieger, S. (Hg.) (2020b): Handbuch Virtualität. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Knebel, S. K. (2001): Virtualität. In: Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie, Bd. 11, hg. v. Ritter, J./Gründer, K./Gabriel, G., Darmstadt: WBG, Sp. 1062-1066.

Levy, P. (1997) Welcome to virtuality In: Digital Creativity, Jg. 8, S. 3-10, DOI: 10.1080/09579139708567068

Rieger, S. (2014): Menschensteuerung. Zu einer Wissensgeschichte der Virtualität. In: Jeschke, S./Kobbelt, L./Dröge, A. (Hg.): Exploring Virtuality. Virtualität im interdisziplinären Diskurs. Wiesbaden: Springer Spektrum, S. 19-43.

Rieger, S./Schäfer, A./Tuschling, A. (Hg.) (2021): Virtuelle Lebenswelten. Körper – Räume – Affekte. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.

Roth, P. (2000): Virtualis als Sprachschöpfung mittelalterlicher Theologen. In: ders./Schreiber, S. (Hg.): Die Anwesenheit des Abwesenden. Theologische Annäherungen an Begriff und Phänomene von Virtualität. Augsburg: Wißner, S. 33-41.

Sprenger, Florian (2020): Ubiquitous Computing vs. Virtual Reality. Zukünfte des Computers um 1990 und die Gegenwart der Virtualität. In: Kasprowicz, D./Rieger, S. (Hg.): Handbuch Virtualität. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, S. 98-109.

Völker, C. (2010): Mobile Medien. Zur Genealogie des Mobilfunks und zur Ideengeschichte von Virtualität. Bielefeld: transcript.

Programm

Das Programm finden Sie hier [Update 18.09.22].

Tagungsbericht

Die Jahrestagung der Kommission Pädagogische Anthropologie in der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft fand vom 21. bis 23. September 2022 an der Fakultät Erziehungswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Dresden statt. Auf der Tagung ging es darum, neben der grundsätzlichen Reflexion über das Verhältnis von Mensch und Virtualität (homo virtualis, digitalis, fictionalis, medialis, utopicus etc.), die Bedeutung von Virtualität für die Beschreibung pädagogisch-anthropologischer Dimensionen und Prozesse zu diskutieren, wie z.B. die Betrachtung von Bildung und Erziehung, Lernen, Bildsamkeit sowie Subjektivierung, Autonomie und Wissen, desgleichen von Körperlichkeit, Vulnerabilität, Gewalt, Mimesis, (Sozial‑)Raum, Ritual, Imagination, Mythos, Kunst und Spiel. Zudem wurde Virtualität als Bedingung menschlicher Weltaneignung in verschiedenen pädagogischen Feldern untersucht, um pädagogische Konzepte und Praktiken auf ihre pädagogisch-anthropologischen Implikationen im Kontext von Virtualität zu befragen. Im Folgenden werden die Schwerpunkte der einzelnen Vorträge kurz zusammengefasst.

Zu Beginn der Tagung setzt sich Carsten Heinze mit Bezug auf Gilles Deleuzes Konzeptionalisierung von Virtualität kritisch mit Klaus Pranges repräsentationslogischer Begründung des ‚Zeigens‘ als ‚Grundgebärde‘ des Erziehens auseinander. Ausgehend von der Deleuzschen Fassung des Virtuellen als reale Problemstruktur, die noch der Aktualisierung bedarf, wird Lernen als unabschließbarer schöpferischer Prozess der Problematisierung beschrieben, der sich der Logik der Repräsentation entzieht. Aus einer phänomenologisch-hermeneutischen Perspektive untersucht Mirka Dickel (Jena) im Anschluss an Klaus Pranges Theorie des Zeigens Lehren und Lernen als zwei Grundoperationen des Unterrichts, die nicht auseinander ableitbar sind. Vor dem Hintergrund der Theorie der Mimesis diskutiert sie die Bedingungen für das Ineinandergreifen der beiden Operationen in den didaktischen Vollzügen des Zeigens und Sprechens, die sie als virtuell interpretiert.

Karina Limonta Vieira und Anna Pesch (Cottbus) setzen sich unter Rekurs auf die Technikphilosophie von Don Ihde mit dem Verhältnis von Körper, Leib und Virtualität auseinander. Dieses Grundverhältnis wird im anschließenden Beitrag von Rouven Seebo (Innsbruck) und Timur Rader (Köln) anhand eines konkreten Fallbeispiels der Optimierung des Selbst auf der Bildplattform Instagram analysiert. Dabei werden digitale Räume als virtuelle Möglichkeitsräume beschrieben, in denen Wandlungs- und Lernprozesse hinsichtlich der dargestellten Selbstbilder zu beobachten sind. Virtualität als das potenziell und zukünftig Mögliche gewinnt im pädagogisch-anthropologischen Zusammenhang Relevanz, wenn man bedenkt, dass Pädagogik ohne anthropologische Vorstellungen nicht möglich ist. Thomas Senkbeil (Solothurn) verweist in seinem Beitrag auf diese bedeutsame Wechselbeziehung und diskutiert, ausgehend von der Analyse des Films „Ich bin dein Mensch“ von Maria Schrader, die Unverfügbarkeit des Menschen, die u.a. in seiner Leiblichkeit sowie seiner Vulnerabilität besteht. Im Anschluss an Villém Flusser interpretiert Florian Krückel (Würzburg) das Virtuelle als eine Eröffnung von Möglichkeitsräumen, die einen poetischen ‚Ent-wurfscharakter‘ besitzen und plädiert davon ausgehend für eine Reaktualisierung des Bildungsbegriffs.

Zum Abschluss des ersten Tages fordert Jörg Zirfas (Köln), angelehnt an Jacques Derrida, die Teilnehmer:innen dazu auf, von Geistern zu lernen. Dabei geht er auf die humanen Formen von und die Beziehungen zu Gespenstern als Erfahrungs-, Erinnerungs- und Antizipationsphänomenen ein, die sich im Laufe des Lebens ereignen.

Der zweite Tag beginnt mit einem Vortrag von Christoph Wulf (Berlin), der sich vor dem Hintergrund der digitalen Transformationsprozesse mit den Gefährdungen des Menschseins im Anthropozän auseinandersetzt und insbesondere im virtuellen Möglichkeitssinn des Menschen eine Voraussetzung dafür sieht, Lösungen für aktuelle Herausforderungen zu finden. In diesem Zusammenhang verweist er u.a. auf das Problem der Gewalt gegen die Natur, gegen andere Menschen und gegen sich selbst. Liesa Schamel und Moritz Krebs (Köln) interpretieren Virtualität unter Rückgriff auf Theorien der Imagination und Repräsentation, die sie von abbildtheoretischen Vorstellungen abgrenzen, als Bedingung der Wahrnehmung von Welt. Am Beispiel des solidarischen Denkens wird der virtuelle Raum als intersubjektiver Imaginationsraum betrachtet, der Vernetzungs-, Unterstützungs- und Befreiungspotenziale eröffnet. Die Rekonstruktion der Wahrnehmbarkeit von Virtualität steht im Zentrum des Beitrags von Jeanette Böhme und Annabelle Bußmann (Essen). Anhand der Untersuchung von Smartphon-Praktiken in „Passagen-Orten“ zeigen sie die Verschränkungen von medialen Wahrnehmungsmodi und medienpraktischen Bewegungsmustern als Syntheseleistungen auf.

Frederike Schmidt und Katharina Bock (Siegen) analysieren die virtuell entworfenen Lebenswelten von Jugendlichen in eigenproduzierten Gangster-Rap-Liedern und interpretieren diese als Spiel mit möglichen Wirklichkeiten im Kontext der Bildung von Selbst- und Weltverhältnissen. Die „Sichtbarmachung des Unsichtbaren“ rekonstruiert Sabine Seichter (Salzburg), indem sie die bildhaften, virtuellen Darstellungen des vorgeburtlichen Embryos im Laufe der Geschichte darstellt. Die Möglichkeit der Erzeugung und damit auch der Darstellung und Inszenierung von pränatalem Leben mithilfe moderner Technik und Medien führen zur anthropologisch bedeutsamen Aufhebung der Grenzen von prä- und postnatalem Leben. Thomas Grunau (Halle) untersucht Meditationsapps für Kinder und fragt nach der Anthropologie der virtuellen Entspannung. Dabei hinterfragt er das jeweils zugrunde liegende Menschenbild der kommerziellen Anbieter dieser Apps.

Siegfried Däschler-Seiler (Stuttgart) setzt sich in seinem Beitrag mit der Virtualisierung der Lehre im Sinne ihrer Digitalisierung auseinander und plädiert im Anschluss u.a. an Kant, Herbart und Schleiermacher für die Rückbesinnung auf die Lehrkunst. Die Bedeutung von virtuellen Möglichkeitsräumen im Leistungssport untersucht Stefanie Jäger (Innsbruck). Sie geht von der These aus, dass sich in diesen Räumen durch das virtuell Erlebte neue Bewegungsformen in einem „Als-ob-Modus“ erschließen bzw. bereits gelernte Bewegungen verbessern und optimieren lassen. Sophia Feige (Jena) widmet sich dem Rollenspiel als Unterrichtsmethode. Dabei interpretiert sie die Rollenübernahme als Imagination des Fremden und nicht, wie üblich, als dessen Auflösung. Dies wird anhand von Pen&Paper-Rollenspielen veranschaulicht.

Ruprecht Mattig (Dortmund) diskutiert in seinem Vortrag die Sichtweise des Menschen als homo tragicus, der durch seinen zukunftsorientierten (virtuellen) sowie verhängnisvollen Entwurfs- und Handlungscharakter charakterisiert sei. Mattig plädiert dafür, den Menschen in einer krisendurchschüttelten Zeit (Anthropozän) anders zu denken und den tragischen Momenten des Seins, die u.a. in Begriffen wie Dilemma, Konflikt und Verhängnis ihren Ausdruck finden, mehr Aufmerksamkeit zu widmen. Im Kontext von Virtualität fragt Matthias Steffel (Salzburg) danach, inwieweit Menschen tatsächlich das sind, was sie zu sein scheinen. Das als-ob als anthropologische Konstante und der Gegensatz von Heuchelei und Wahrhaftigkeit werden philosophisch- und kulturgeschichtlich rekonstruiert. Robert Schneider-Reisinger (Salzburg) untersucht mit Bezug auf die materialistische Pädagogik Virtualität als Modus des „Noch-nicht“ in der Metapher des Spiegels, anhand derer er modellhaft die Bedingungen menschlicher Erfahrung und Erkenntnis rekonstruiert. Vor dem Hintergrund des Verständnisses der virtuellen Welt als Utopie, d.h. als mögliche Welt, die als Konstrukt eine Wirkung auf Wirklichkeit entfalten kann, fragt Konstantinos Masmanidis (Dresden), ob Anarchismus bzw. ein auf dem Anarchismus basierendes Bildungs- und Erziehungskonzept als eine virtuelle Welt bezeichnet werden kann.

Insgesamt wurden auf der Tagung sowohl wesentliche Aspekte als auch offene Forschungsfragen zur Bedeutung der Virtualität als Bedingung menschlicher Weltaneignung aus einer pädagogisch-anthropologischen Perspektive aufgezeigt und damit zugleich die Notwendigkeit einer Pädagogik der Virtualität verdeutlicht. Ein Tagungsband befindet sich in Vorbereitung.

(Peter Bauer, Konstantinos Masmanidis, Carsten Heinze)