Studying at the Chair of Silviculture

It is a central concern and challenge of our professorship to convey this discipline to students in a vivid way through a wide range of courses and teaching formats and to inspire them with enthusiasm for the complex interrelationships.

© Fischer

© Fischer

Courses in the subject "Silviculture"

The long tradition of silviculture dates back to the 18th century. It was Heinrich Cotta who first coined the term "silviculture" in his seminal work Anweisung zum Waldbau (1817).

On the basis of empiricism (experience and observation), logic (lawful reasoning) and finally groundbreaking scientific research, modern silviculture finally developed. Today, it provides us with a solid range of diverse possibilities for establishing, shaping, harvesting and rejuvenating a vital, efficient forest that meets the required ecosystem services.

It is a central concern and challenge of our Chair to convey this discipline to students through a range of courses and teaching forms and to inspire them with enthusiasm for the complex interrelationships.

It goes without saying that knowledge of forest ecology and silvicultural methodology have developed dynamically. Although various important directions of development can be foreseen, it is difficult to say today what knowledge will remain essential for graduates in the course of their future careers. Even if it could be foreseen, it would certainly not be possible to convey it in its entirety within the framework of a degree course.

The aim is therefore to teach students more than "just" facts. Rather, subject areas are structured independently with regard to relevant stakeholders (forest owners), objectives (forest functions and services) and framework conditions (climate change). This enables graduates to apply the silviculture knowledge acquired during their studies to new problems and situations depending on the context. The courses in silviculture should therefore contribute to recognizing relevant knowledge as such, organizing structured learning processes independently and expanding or generating new knowledge on forest management as required.

Challenges of good silviculture teaching - in the Bachelor's and Master's degree programs

Bachelor's degree program

The bachelor's degree in forestry has been established as the first degree at German universities that qualifies students for a career, and compared to the previous curricula at universities, it is clear that there are good career opportunities even after these three years of study. A central goal of the Bachelor's courses, especially in silviculture, is therefore to prepare students for a specific professional field of activity or a possible range of activities.

This results in challenges for our teaching: it serves to provide orientation about job profiles and possible career paths in practice, which are easier to follow today than they were 25 years ago. This is important in order to generate a willingness to learn and self-interest and to maintain the associated motivation to learn throughout the course of study.

In the Bachelor's degree program, the courses aim to impart theoretically sound specialist knowledge. Without exception, the teaching modules are interdisciplinary and are organized with colleagues from networked Institutes. They include a limited specialization based on a broadly diversified basic knowledge.

The teaching of the Chair of Silviculture therefore only begins in the second year of the Bachelor's degree program in Forest Sciences, at a time when a foundation for understanding the biotic and abiotic processes in the forest ecosystem has already been laid: soil and site science and material balance, botany and dendrology, wildlife ecology, forest metrology and biometrics.

We therefore start in the third semester with a practice-oriented introduction to the management of temperate forests and their technological implementation (B11). This is followed in the fourth semester by "Cutting methods, natural regeneration methods and genetic implications" (B16) and, together with colleagues from Forest Resource Economics, "Profitable stand management" (B15) and finally, in the fifth semester, all important silvicultural issues in the context of artificial regeneration and afforestation (B33). It is not until the Master's degree course that we delve deeper into the functional orientation of silviculture and the special ecology of natural forest regeneration.

Our courses in silviculture at Bachelor's level always serve to train analytical and structured thinking. This is associated with the training of the ability to abstract and to condense theoretical knowledge from previous or parallel basic subjects such as biometrics, soil science, nature conservation, ecology or yield science, taking into account concrete framework conditions and transferring it to silvicultural issues. The modules in silviculture thus lay the foundation for later context-dependent problem-solving behavior.

Master's program

The basic knowledge and limited specialist knowledge of the Bachelor's course is extended in the Master's course. In the modules "Operational planning and management in the course of function-oriented forest management" (FOMF 2) and "Habitat design in forests" (FOMF14), students aim to position themselves. This requires the definition and interpretation of (even supposedly) divergent doctrinal opinions. This is linked to a further requirement for silvicultural training: University teaching in silviculture should make students self-aware and will not avoid dealing with its own teaching content and opinions. What's more, it must leave enough room for opposing views and experiences. In this way, we hope to realize the ambition of training both future researchers and managers in the Master's course in silviculture.

At the latest here in the Master's program, students are naturally involved in teaching-learning arrangements that encourage them to actively participate in research and teaching and to become jointly responsible for their own progress and findings. The courses - whether lecture, exercise or excursion - are designed in such a way that exemplary questions are developed and the field of silviculture research becomes a natural part of teaching.

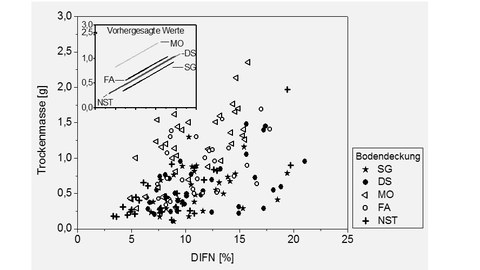

Particularly in the silviculture course "Habitat design in forests", which is organized together with colleagues from forest zoology, students carry out their own research-based work, the results of which are discussed in the seminars. This results in smaller research projects that are carried out and summarized for evaluation as part of a course.

A further feature of the teaching concept is the opportunity for students to be involved in the development, implementation and evaluation of research projects as a matter of course and thus acquire research skills. Students can work on the various requirements of their examination regulations, such as tutoring or project bills, assignments or qualification theses (Master's theses) arising from the research projects at the Chair of Silviculture and at the same time help to shape scientific research. For example, the course-related assignments are largely based on collaboration in a student group. Through intensive collaboration and supervision, students gain a deep insight into the fields of forest ecology, botanical and plant-sociological relationships and interactions with the site, all of which are important for the silvicultural treatment of individual stands.

The quality of silviculture teaching is particularly successful when research, evaluation and documentation are anchored in teaching in such a way that "new findings" can also be developed by and with students with each new teaching module. In particular, continuity in advising must be balanced with regard to the uncertainties that arise for students in this form of teaching and learning and to remain open and supportive in all questions, especially with regard to the active design of one's own thematic focus.

We try to strengthen and support students with regard to their study biography planning. The basic conditions for this are openness, time and responsiveness.

As part of our cooperation with related scientific institutions and forestry practice, contributions from external advisors are incorporated into the modules. However, offers of specialist discussion or support in arranging contacts do not cancel out the students' own responsibility. In this context, we therefore see our task in silviculture primarily as providing impetus or opening doors . Everyone has to step in themselves.