MOTUS - Mobilitätstransformation: Schlüsselfaktoren für nachhaltigen und resilienten Verkehr

Der MOTUS-Ansatz als Regelkreis

Übersicht

Im Projekt MOTUS wird untersucht, wie sich disruptive Ereignisse auf die Mobilität in Städten auswirken. Dabei liegt der Fokus auf der Sicherheitsanalyse im Verkehrssystem, insbesondere auf den Auswirkungen solcher Ereignisse auf die Verkehrssicherheit. Komplexe Verkehrssituationen werden simuliert, um Verbesserungen und Sicherheitsmaßnahmen zu entwickeln.

Ein weiteres Ziel des Projekts ist die Analyse des Mobilitätsverhaltens bei disruptiven Ereignissen. Hierzu wird ein Modell entwickelt, das auf Befragungen von 15.000 Personen basiert, um zu verstehen, wie solche Ereignisse das Verkehrsverhalten verändern und wie Verkehrssysteme resilient gestaltet werden können.

Mobilfunkdaten werden genutzt, um detaillierte Analysen zur Mobilität durchzuführen. Diese Daten ermöglichen es, Verkehrsströme feingranular zu untersuchen und Verkehrsmittel zuverlässiger zu identifizieren, insbesondere für kürzere Distanzen unter 30 km.

Zusätzlich wird ein Modell zur Analyse von Verkehrsnachfrage und -fluss entwickelt. Dieses Modell verwendet Daten zur Stadtstruktur, Mobilitätsdynamik und soziodemografischen Faktoren, um zu verstehen, wie geändertes Mobilitätsverhalten die städtischen Verkehrsströme beeinflusst. Ziel ist es, allgemeingültige Erkenntnisse zur nachhaltigen und resilienten Mobilität zu gewinnen.

Die Bewertung der Nachhaltigkeit im Verkehrssystem umfasst die Analyse von CO2-Emissionen, Verkehrslärm, Luftschadstoffen, Kosten und Verkehrssicherheit. Diese Bewertungen helfen dabei, nachhaltige Verkehrsstrategien zu entwickeln und die Auswirkungen verschiedener Szenarien und Maßnahmen zu bewerten.

Das Team freut sich darauf, die Ergebnisse der Forschung im Rahmen des Projekts MOTUS zu präsentieren.

Podcast

Podcast: Vorstellung vom MOTUS-Projekt

(english transcript available below)

Vorwort:

Hallo liebe Podcast-Hörer, schön, dass Ihr zu uns gefunden habt.

Mein Name ist Lara Efinger und ich arbeite als Business Development Managerin bei Teralytics. Gemeinsam mit der TU Dresden und der Uni Kassel sind wir Teil des mFund Projektes MOTUS, welches wir Euch gerne im Folgenden näher vorstellen möchten.

KAPITEL 1: Max Bäumler von der TU Dresden

Hallo Max, möchtest Du Dich und Deine Forschung kurz vorstellen?

Mein Name ist Maximilian Bäumler, ich bin 30 Jahre alt und ich forsche an der TU Dresden zur Vorhersage von Unfällen an Knotenpunkten innerhalb von MOTUS.

Wie kam es überhaupt dazu, dass das MOTUS Projekt entstanden ist?

Vielen Dank für die Frage, Lara!

Ich denke, es ist super spannend sich zunächst anzuschauen, wie MOTUS entstanden ist.

Ich weiß noch, es war kurz zu Beginn der Pandemie, der erste Lockdown im Jahr 2020, und wir hatten gesehen, hier an der TUD, dass sich das Verkehrsverhalten drastisch verändert hat. Die Straßen waren plötzlich leer, man hat keine Autos mehr gesehen, es waren wesentlich weniger Fußgänger unterwegs und unabhängig voneinander haben sich mehrere Lehrstühle gedacht, dass sie dies unbedingt erfassen und untersuchen müssen. Das heißt, die Verkehrspsychologen haben angefangen, Befragungen zum geänderten Mobilitätsverhalten durchzuführen und auch wir z.B. am LKT haben Videobeobachtungen durchgeführt und Kreuzungen gefilmt und uns angeschaut, wie das Verkehrsverhalten aussieht. Und nachdem wir uns dann irgendwann mal zusammengefunden haben, weil wir gemerkt haben, dass wir alle Daten aufgenommen haben und wir diese Daten zusammenbringen müssten, haben wir gesagt, lasst uns zusammen das MOTUS Projekt machen und lasst uns hier untersuchen, was denn bei so disruptiven Ereignisse, wie einer Pandemie, eigentlich passiert und wie sich diese Ereignisse auf das Verkehrsgeschehen in Städten auswirken.

Für was steht die Abkürzung MOTUS denn überhaupt?

Für was steht MOTUS überhaupt? MOTUS kommt aus dem Lateinischen und heißt erstmal Bewegung. Und innerhalb unseres Projektes haben wir MOTUS praktisch benutzt, um ein Akronym zu bilden, nämlich aus den Worten: MOTUS – MObilitätsTransformation: Erkenntnisse zU Schlüsselfaktoren für nachhaltigen und resilienten Verkehr. Im Endeffekt ist das Akronym aus MOTUS nicht gleich ersichtlich, deshalb merkt euch einfach, MOTUS heißt Bewegung und um Bewegung und Verkehr geht es in unserem Projekt.

Und wie genau möchte das Projekt MOTUS das erreichen?

Kurz und knapp geht es in MOTUS darum, dass wir auch in Zukunft oder vor allem in Zukunft nachhaltige und resiliente Verkehrssysteme in Städten haben sollten. Was heißt das konkret?

Wir möchten es schaffen oder wir möchten Kommunen vor allem befähigen, dass sie jetzt schon vorsorgen, damit egal, was in Zukunft passiert, ob es irgendein Klimawandelereignis ist, ob es nochmal eine Pandemie ist, oder ob es auch ein Strukturwandel ist, dass ihr Verkehrssystem in ihrer Stadt nachhaltig und resilient ist. Und vor allem auch bleibt.

Resilient heißt hier vor allem Widerstandsfähigkeit, d.h. wenn wir uns jetzt eine Stadt vorstellen und wie der Verkehr in dieser Stadt funktioniert, mit dem ÖPNV (Bussen und Bahnen), mit dem Fahrradverkehr und auch mit dem Autoverkehr, dann möchten wir es schaffen, jetzt Empfehlungen zu erarbeiten, für Kommunen und Bürgermeister, dass sie vorsorgen können, wenn wieder eine Pandemie passiert, sodass der Verkehr trotzdem nachhaltig ist.

Das heißt, es könnte z.B. sein, dass in der nächsten Pandemie, so wie in der Corona-Pandemie, die Leute aus Angst sich anzustecken, erstmal den ÖPNV meiden und aufs Auto umsteigen. Und das könnte rein hypothetisch bedeuten – wir haben es noch nicht bewiesen – dass durch den Umstieg aufs Auto mehr CO2 Emissionen ausgestoßen werden oder auch wieder mehr Unfälle mit Autos passieren. Und dies ist in unserem Sinne nicht nachhaltig, sondern eher kontraproduktiv.

Und nun wäre es interessant, welche Maßnahmen müsste eine Kommune ergreifen, damit genau dies verhindert wird in der nächsten Pandemie, also z.B. die Taktzahl im ÖPNV erhöhen, desinfizieren oder die Leute sensibilisieren, wenn ihr euch so und so verhaltet, dann müsst ihr keine Angst vor Ansteckung haben.

Und das interessante ist, in MOTUS möchten wir nicht nur Pandemien anschauen, sondern wir möchten allgemein sagen, wie könnt ihr euch auf disruptive Ereignisse vorbereiten. Und dafür haben wir uns gedacht, wir schauen uns einerseits den Klimawandel an sowie die Pandemien oder zukünftige Pandemien, als auch disruptive Ereignisse, wie z.B. Strukturwandel in Braunkohlerevieren.

All das kann nämlich ein Verkehrssystem komplett auf den Kopf stellen – von einem Tag auf den anderen oder auch langfristig - und deshalb ist es interessant, sich jetzt schon zu überlegen, was könnt ihr als Kommunen machen, damit euer System trotz dieser Ereignisse nachhaltig und resilient ist.

Und wie will MOTUS das erreichen?

Nun haben wir ein wirklich großes Ziel in MOTUS und die Frage ist natürlich, wie schaffen wir es nun, diese Maßnahmen für die Kommunen zu erarbeiten, damit sie wissen, was sie machen können, damit ihr Verkehrssystem auch in Zukunft nachhaltig ist und bleibt.

Und dafür möchten wir am Schluss eine Simulationsplattform haben, d.h. man kann sich vorstellen, man ruft unsere Plattform auf und dann kann man verschiedene Szenarien durchspielen, wie den Klimawandel oder Pandemieszenarien oder Strukturwandelszenarien und bekommt dann eine Empfehlung, welche Maßnahmen man ergreifen sollte, damit das Verkehrssystem nachhaltig und resilient bleibt.

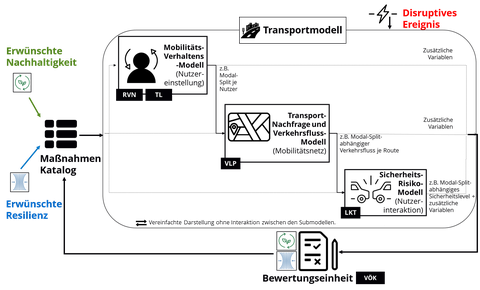

Und diese Simulationsplattform baut auf einem Modell auf und dieses Modell wiederum ist wie ein Regelkreis aufgebaut. Das heißt, wir schauen uns erstmal an, wie schaut der Verkehr in einer Stadt abstrahiert aus, wie verhalten sich die Nutzer, wie fahren die Nutzer durch die Stadt und wie bewegen sie sich und wie viele Unfälle passieren dabei, bewerten das Ganze, überlegen uns dann, ok das Ganze ist schon sehr nachhaltig oder ist es noch weniger nachhaltig und wenn z.B. herauskommt, es ist gerade im Moment weniger nachhaltig, dann würden wir sagen, wir müssten noch Maßnahmen ergreifen, um dieses System zu verbessern. Dann spielen wir diese Maßnahmen ein und schauen wieder, wie sich die einzelnen Modelle verhalten.

Und vielleicht nochmal detaillierter aufgeschlüsselt, wie ihr euch das vorstellen könnt: Unser Hauptmodell ist wie eine Treppenstufe:

Ganz am Anfang steht das Mobilitätsverhaltensmodell, in diesem schauen wir uns an, wie die Nutzereinstellung ist, also d.h. wohin möchten die Nutzer überhaupt reisen, warum möchten sie durch unsere Stadt reisen und welches Verkehrsmittel möchten sie nutzen?

In unserem zweiten Modell, dem Transportnachfrage- und verkehrsflussmodell (schwieriger Name) schauen wir uns dann an, wie sich die Nutzer durch unsere abstrakte Stadt bewegen. D.h. wohin fahren sie genau? Welche Straße nehmen sie exakt mit ihrem Fahrzeug, z.B. mit dem Auto oder mit dem Fahrrad?

Und danach kommt unser Sicherheitsrisikomodell und das heißt, wir zoomen nochmal tiefer rein und wir schauen uns für einzelne Kreuzungen an, wie viele Unfälle passieren gerade, abhängig davon, welche Verkehrsteilnehmer unterwegs sind und wie die sich durch die Stadt bewegen.

Und am Schluss nehmen wir die Ergebnisse von all diesen Modellen, die wie eine Treppenstufe angeordnet sind, und versuchen das Ganze zu bewerten. Also passieren jetzt viele Unfälle? Werden gerade viele CO2-Emissionen ausgestoßen, weil z.B. viele Autos unterwegs sind oder nicht, erarbeiten dann einen Bewertungsscore für die Nachhaltigkeit und die Resilienz und entscheiden uns dann, welche Maßnahmen ergriffen werden müssen. Und gleichzeitig ist es so – jetzt können wir uns diesen Ablauf für den Normalfall anschauen – und wir werden uns diesen Ablauf auch für disruptive Ereignisse, wie eben Pandemie, Klima- und Strukturwandel anschauen, und uns dann wieder überlegen: Wie verändert sich diese und jene Größe in Abhängigkeit unseres disruptiven Ereignisses? Und im Folgenden werden wir euch nun einen Einblick geben, wie denn diese einzelnen Modelle funktionieren sollen.

Nachdem Du uns jetzt das Projekt vorgestellt hast, möchtest Du uns noch etwas dazu erzählen, worum Du Dich im Projekt kümmerst?

Meine Aufgabe ist es, das letzte Modell in der Treppenstufe, die wir heute schon mal gehört haben, die Treppenstufe der Modelle, zu modellieren. Nämlich das Unfallvorhersage oder auch Sicherheitsrisikomodell. D.h. in meinem Aufgabenbereich, in meiner Forschung zoomen wir auf spezifische Knotenpunkte in unserer Simulation und überlegen uns, welche Unfälle und wie viele Unfälle pro Jahr würden jetzt bei einem gegebenen disruptiven Szenario oder auch beim Normalzustand entstehen und genau diese Zahl melden wir dann an die Bewertungseinheit, die dann bewerten kann, ob das Verkehrssystem nachhaltig und resilient ist. Um das Ganze zu modellieren, schauen wir uns an, wie die Fahrzeuge fahren, wie diese miteinander interagieren, wie die Verkehrsteilnehmer miteinander interagieren, versuchen das Ganze zu beschreiben und dann eben basierend auf Extremwerten ein Unfallvorhersagemodell zu bauen.

KAPITEL 2: Paul Papendieck von der Uni Kassel

Um das Mobilitätsverhaltensmodell in MOTUS kümmert sich vor allem Paul Papendieck. Paul ist als Verkehrspsychologe an der Uni Kassel und ist dort am Institut für Verkehrswesen für MOTUS zuständig. Paul, was ist denn eigentlich ein disruptives Ereignis?

Grundsätzlich kann man das Wort disruptiv im Kontext der Verkehrsforschung mit „unterbrechend“ übersetzen. Wir wollen uns also ansehen, wie bestimmte Ereignisse die normalen alltäglichen Gewohnheiten im Straßenverkehr unterbrechen. Wie Max ja schon erzählt hat, ist ein Paradebeispiel für ein disruptives Ereignis die Corona Pandemie gewesen: Da passiert auf einmal irgendeine externe Sache, irgendein Virus, und das führt dazu, dass ich mir auf einmal überlege, ob ich nicht den ÖPNV erstmal vermeide und für den Weg zur Arbeit doch erstmal lieber auf das Fahrrad oder das Auto umsteige. Oder vielleicht bin ich auch ganz grundsätzlich weniger zur Arbeit unterwegs, weil mein Arbeitgeber vielleicht HomeOffice Regelungen eingeführt hat – und so weiter und so fort. Das bedeutet, das ganze Verkehrssystem, also das Zusammenspiel zwischen den einzelnen verschiedenen Verkehrsmitteln auf den Straßen, Schienen und Wegen in einer Stadt ist auf einmal durcheinandergebracht.

Und wir wollen herausfinden, welche anderen Ereignisse es noch gibt, die das Zusammenspiel durcheinanderbringen können und vor allem wie wir Verkehrssysteme konzipieren können, die das abkönnen, die also nicht sofort in Stau und Chaos versinken, weil die eingespielten Mechanismen durcheinandergebracht worden sind. Dabei denken wir im Kontext von MOTUS zum Beispiel an Extremwetterereignisse im Zuge des Klimawandels, an strukturelle Veränderungen in einem Ort und so weiter.

Was meinst du denn mit strukturellen Veränderungen in einem Ort?

Ein Beispiel dafür könnten Orte sein, die vom Strukturwandel betroffen sind, der durch die Energiewende aufkommt. Es gibt in Deutschland einige Orte, die beispielsweise sehr stark davon geprägt sind, dass vor Ort Braunkohleabbau stattfindet. Nachdem Deutschland von der Braunkohle wegkommen will, werden diese Orte zwingendermaßen in naher Zukunft große Veränderungen erleben oder tun das jetzt schon. Arbeitswege verändern sich, vielleicht gibt es größere Infrastrukturprojekte, ein sich veränderndes kulturelles Angebot, und so weiter. Und all das hat natürlich Einfluss darauf, wie Menschen in diesen Regionen unterwegs sind, welche Ziele sie haben und wer überhaupt unterwegs ist. In den vergangenen Jahrzehnten gab es strukturelle Veränderungen dieser Art zum Beispiel im Ruhrgebiet.

Ha, das ist ja spannend! Und wo kommst du da jetzt ins Spiel?

Als Verkehrspsychologe interessiert mich natürlich am meisten das Verhalten von einzelnen Verkehrsteilnehmenden: Wie sind die unterwegs, welche Verkehrsmittel nutzen die, welche Ziele haben sie und wie verändern die ihr Verhalten, wenn ein disruptives Ereignis eintritt? Max hat ja schon erwähnt, dass der erste Schritt im Projekt das Mobilitätsverhaltensmodell ist und für genau das bin ich verantwortlich.

Kannst du dieses Mobilitätsverhaltensmodell noch genauer beschreiben?

Wir planen für MOTUS eine großflächige Befragung, die individuelles Verkehrsverhalten erfassen soll. Dafür haben wir eine Online-Befragung konzipiert, in der insgesamt 15.000 Menschen aus Dresden und unseren beiden Modellkommunen Bad Hersfeld und Leipzig dazu aufgerufen sind, einen Fragebogen zu ihren Verkehrsgewohnheiten auszufüllen. Natürlich freuen wir uns auch über Teilnehmende aus allen anderen Regionen Deutschlands. In diesem Fragebogen erfassen wir zum einen alltägliche Verkehrsgewohnheiten der Teilnehmenden, also „was für Ziele haben sie im Alltag“, „welche Verkehrsmittel benutzen sie“. Zum anderen fragen wir aber auch, ob die Leute schon einmal Erfahrungen mit disruptiven Ereignissen gemacht haben, die ihre Verkehrsgewohnheiten verändert haben. Aus diesen Angaben berechnen wir im Anschluss typische Verhaltensmuster, wie bestimmte Gruppen von Menschen auf bestimmte Arten von Ereignissen reagieren. Das könnte beispielsweise so etwas sein wie: Junge Leute unter 28 wechseln eher aufs Fahrrad, wenn der Bus oder der Zug ausfällt, Menschen ab 35 dagegen wechseln eher aufs Auto. Das heißt also sowas wie das Alter könnte hier eine Rolle spielen, das nur als Beispiel, aber auch Persönlichkeitseigenschaften können da wichtig sein, Einkommensschichten, Berufsgruppen, leben die Leute auf dem Land oder in Großstädten und so weiter. Und diese Informationen geben wir dann eben gebündelt in solche typischen Verhaltensmuster weiter an Angelika und Andreas, die diese Informationen für das Transportnachfrage- und verkehrsflussmodell verarbeiten.

Allerdings sind das nicht die einzigen Informationen, die im Mobilitätsverhaltensmodell entstehen, auch du Lara hast ja noch eine wichtige Rolle mit Teralytics. Erzähl doch mal!

KAPITEL 3: Lara Efinger von Teralytics

Ja klar, sehr gerne.

Wir bei Teralytics nutzen Mobilfunkdaten, um daraus verschiedenste Analysen zur Mobilität der Menschen zu erstellen. In Deutschland nutzen wir dafür Daten der Telefónica, welche wir mit regionalen Marktanteilen auf die Gesamtbevölkerung hochrechnen.

Oft wird dabei angenommen, dass wir die direkten Standortdaten der SIM-Karten bekommen und diese dann direkt in Bewegungsprofile umrechnen können. Leider ist es aber nicht ganz so einfach, denn wir bekommen lediglich die Verbindungdaten der SIM-Karten mit den Mobilfunkmasten. Diese werden auch gar nicht so häufig ausgelöst,

durchschnittlich nur etwa alle paar Minuten. Außerdem beinhalten die Daten viele Schiefen, welche wir erst durch Evaluierungen und Umrechnungen, wozu wir unter anderem Machine Learning einsetzen, berichtigen müssen. Zum Glück haben wir inzwischen aber bereits über 10 Jahre Erfahrung, weswegen wir auch regelmäßig unsere Datensätze mit verbesserter Qualität updaten und neue Produkte vorstellen können.

Im MOTUS Projekt, stellen wir unseren Datensatz „Matrix Kurzdistanz“ zur Verfügung. Hier haben wir mit Rücksicht auf die Infrastruktur der Mobilfunkmasten eine feingranulare Zonierung, mit der sich dann auch sehr gut die im Projekt ausgewählten Verkehrsbereiche der Modellkommunen analysieren lassen.

Bei den Daten im Matrix Datensatz handelt es um klassische Quelle-Ziel Matrizen, welche das Reiseverhalten von Gruppenbewegungen ausgeben. Mit Rücksicht auf die deutschen Datenschutzbedingungen, dürfen wir nämlich erst dann Daten ausgeben, wenn mehr als 5 hochgerechnete Personen eine Reise getätigt haben. Eine Reise ist dabei so definiert, dass die SIM-Karte sich für mindestens 30 Minuten an dem Start- bzw. Zielort aufgehalten haben muss. Die Reiseroute ist dabei nicht berücksichtigt und wird auch nicht in den Daten mit ausgegeben. Durch dieses Vorgehen haben wir neben der feinen Zonierung so auch die Möglichkeit die Daten stündlich auszugeben. Damit genug Verflechtung den Grenzwert von 5 erreichen, werden die Wochentage eines Monats summiert. Wir rechnen also alle Montage, Dienstage usw. im Monat zusammen. Dadurch ergibt sich dann die Möglichkeit bspw. die Reisedaten eines typischen Montags im Dezember auszuwerten.

Innerhalb des MOTUS Projekts möchten wir nun daran forschen, wie wir die Daten noch feiner aufsplitten können. Konkret soll es dabei um die zuverlässige Detektierung von Verkehrsmitteln gehen. In unserem Matrix Langdistanz Datensatz können wir bereits zwischen Straße, Schiene und Luft ab einer Reisedistanz von 30km unterscheiden. Dies wollen wir nun auf die nächste Stufe heben und auch für Reisen unter 30km ermöglichen. Wir hoffen dies durch ein neues Berechnungsverfahren der Reiserouten sowie unter Einbezug verschiedenster Vergleichsdaten zu erreichen. Im ersten Schritt sollen dabei erst einmal kleinere Regionen untersucht werden, das endgültige Ziel ist es aber natürlich, die Aufsplittung in unseren Matrix Datensätzen Flächendeckend für alle Länder anbieten zu können.

KAPITEL 4: Angelika Hirrle von der TU Dresden

Als nächste möchten wir Euch nun Angelika vorstellen.

Dr. Angelika Hirrle ist wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin am Lehrstuhl für Verkehrsprozessautomatisierung an der TU Dresden.

Angelika, Ihr entwickelt im Projekt MOTUS das Nachfrage- und Verkehrsflussmodell. Was genau beschreibt das?

Dieses Modell ist eingebettet zwischen dem Mobilitätsverhaltensmodell, das Paul entwickelt und dem Sicherheitsrisikomodell von Max. Während Paul untersucht, wie sich das Mobilitätsverhalten der Menschen bei disruptiven Ereignissen ändert, wollen wir verstehen, wie sich dieses geänderte Verhalten auf die städtische Mobilität und den Verkehr auswirkt. Dabei nehmen wir zunächst eine Vogelperspektive ein und schauen uns Verkehrsströme in der Stadt an. Danach zoomen wir faktisch an verschiedenen Kreuzungen in diese Verkehrsströme hinein und betrachten die einzelnen Verkehrsteilnehmenden in den Strömen. Max blickt dann in seinem Sicherheitsrisikomodell auf die Interaktion dieser Verkehrsteilnehmenden.

Wie kann man sich denn dieses Modell dann genau vorstellen?

Das Modell basiert auf der Sammlung und Auswertung einer großen Menge an Daten. Diese Daten kann man in verschiedene Kategorien einteilen. Zum einen nutzen wir Daten, die eher die Topologie einer Stadt beschreiben, also zum Beispiel das Verkehrsnetz mit Straßen, Kreuzungen, Radwegen und ÖPNV-Infrastruktur. Aber auch Gebäude mit ihren Funktionen wie Schulen, Einkaufszentren und Museen fallen darunter. Zum Zweiten verwenden wir Daten, die die Dynamik, also die Bewegung der Menschen in der Stadt beschreiben. Das sind beispielsweise Start-Ziel-Beziehungen, die aus Mobilfunkdaten abgeleitet werden und in unser Projekt durch Teralytics eingebracht werden. Aber auch Informationen zum Verkehrsfluss, wie sie aus mobilen oder festverbauten Zählstellen gewonnen werden, nutzen wir, wenn sie zur Verfügung stehen. Und die dritte große Kategorie sind so genannte soziodemografische Daten. Darunter fassen wir Informationen zu den Menschen wie Alter, Geschlecht, Bildungshintergrund, aber auch Reisewege und Gründe zusammen. Derartige Informationen stehen zum einen in offenen Datenbanken der Städte bereit oder aber werden in Umfragen gewonnen.

Wir analysieren diese Daten und bauen Simulationen auf. Die Simulationen haben den Vorteil, dass wir verschiedene Szenarien durchspielen können, die es so in der Realität nicht gibt. Wir können modellbasiert überlegen, was unter bestimmten Randbedingungen passieren würde und können so untersuchen, welche disruptiven Ereignisse welche Dynamiken hervorrufen und welchen Einfluss bestimmte Maßnahmen haben.

Sind denn diese Modelle allgemein gültig oder gelten sie nur für eine bestimmte Stadt oder eine bestimme Region?

Das Ziel ist es, allgemeingültige Aussagen zur Mobilität in Städten treffen zu können. Durch die Auswertung und Verknüpfung all der Daten und Simulationen wollen wir verstehen, wie die topologische Struktur einer Stadt und die Dynamik in ihr zusammenspielen und welche soziodemografischen Faktoren entscheidenden Einfluss haben. So liegt zum Beispiel die Vermutung nahe, dass die Bewegungsmuster von bestimmten Nutzergruppen abhängig davon sein werden wie heterogen, also verstreut ihre Ziele im Stadtgebiet liegen, denken wir beispielsweise an Pendlerströme, die natürlich von der Anzahl und Lage der Arbeitsstätten abhängen werden. Aber auch die Gestaltung des Angebots an Einkaufsmöglichkeiten und Freizeitangeboten wird die Dynamik beeinflussen.

Im Projekt MOTUS geht es ja darum, Schlüsselfaktoren für resiliente und nachhaltige Mobilität zu identifizieren. Wie kann man sich den Einsatz davon in Eurem Modell vorstellen?

Wenn wir die Beziehung zwischen topologischer Struktur einer Stadt, der Dynamik in ihr sowie soziodemografischen Faktoren kennen, können wir dann auch Aussagen ableiten in welcher Weise Nachhaltigkeit und Resilienz einer Stadt mit der Mobilität der Menschen in Zusammenhang stehen.

Ziel ist es, zu verstehen, wie sich die Dynamik im Fall disruptiver Ereignisse ändert, was die Hauptparameter sind, die diese Veränderungen hervorrufen und wie man diese Veränderungen vorhersagen kann basierend auf ganz bestimmten topologischen und soziodemografischen Faktoren. Das ist die Grundlage dafür zu überlegen, welche Maßnahmen ergriffen werden sollten, um eine bestimmte Dynamik zu beeinflussen. Wie muss beispielsweise das Angebot des ÖPNV geändert werden, um eine nachhaltige Mobilität zu gewährleisten? Wie muss das städtische Verkehrssystem gestaltet sein, damit es robust gegenüber Störungen ist? Und wie muss die Topologie der Stadt, aber auch das Mobilitätsangebot gestaltet sein, dass es beispielsweise als senioren- oder familienfreundlich wahrgenommen wird.

KAPITEL 5: Julia Gerlach von der TU Dresden

Die Diplom-Ingineurin Julia Gerlach ist ebenfalls von der TU Dresden und arbeitet als wissenschafliche Mitarbeiterin bei der Professur für Verkehrsökologie.

Julia, du bist im Projekt für die Nachhaltigkeitsbewertung zuständig. Was ist denn eigentlich die Bedeutung von Nachhaltigkeit?

Na es gibt ja diese berühmte Definition von nachhaltiger Entwicklung aus dem Brundtland-Bericht und da heißt es, dass nachhaltige Entwicklung eine Entwicklung ist, die den Bedürfnissen der Menschen gerecht wird, ohne die Fähigkeit zukünftiger Generationen zu beeinträchtigen, ihre eigenen Bedürfnisse zu befriedigen.

Das heißt jetzt für den Verkehrsbereich, dass wir das Verkehrssystem so gestalten müssen, dass Menschen problemlos ihren Aktivitäten nachgehen könne, dass sie mobil sein können, ihre Ziele erreichen, aber auch, dass das so umweltfreundlich sein muss, dass wir unseren Kindern und Enkelkindern nicht z.Bsp. durch übermäßigen Ressourcenverbrauch, durch unsere CO2-Emissionen oder ähnlichem die Lebensgrundlage wegnehmen.

Also wird im Projekt geprüft, wie klimafreundlich die Menschen unterwegs sind?

Ja genau! Die Höhe der CO2-Emissionen im Verkehr ist eine entscheidende Stellschraube für nachhaltige Entwicklung.

Aber das ist nicht die einzige relevante Wirkung. Nachhaltigkeit basiert ja auf den drei Säulen: Umwelt, Wirtschaft und Soziales. Und wir schauen uns dann im Bereich Umwelt auch noch Verkehrslärm und die Emissionen von Luftschadstoffen an.

Aus wirtschaftlicher Sicht geht es dann vor allem um die Kosten, die z. B. für den Erhalt der Verkehrsinfrastruktur oder auch den Betrieb von Bussen und Bahnen verursacht werden. Bei den sozialen Wirkungen bewerten wir dann z. B. die Verkehrssicherheit.

Für jede einzelne dieser Wirkungen wird eine Zielstellung formuliert, im Bereich des Klimaschutzes z. B. in Anlehnung an das deutsche Klimaschutzgesetz. Das ja sagt, dass wir als Deutschland bis 2045 klimaneutral sein wollen. Und wir können dann für jede einzelne Zielstellung bewerten, wie gut wir da auf dem Weg sind. Und zum Schluss fassen wir diese einzelnen Bewertungen zu einer Gesamtbewertung zusammen. Diese verändert sich dann, je nachdem welche Szenarien oder auch Gegenmaßnahmen für eine Pandemie u.ä. modelliert werden.

Schlusswort:

Vielen Dank Julia und auch vielen Dank nochmal an Max, Paul und Angelika für die Vorstellung Eurer Arbeitspakete im MOTUS Projekt. Vielen Dank auch an alle, die bis hierhin zugehört haben. Wir hoffen, dass wir Euch unser Projekt näher bringen konnten und freuen uns, wenn Ihr nochmal einschaltet, wenn wir dann die Ergebnisse aus unserem Projekt vorstellen dürfen. Auf Wiederhörn!

English Version:

Introduction:

Hello dear podcast listeners, it's great that you've found us.

My name is Lara Efinger and I work as a Business Development Manager at Teralytics. Together with the TU Dresden and the University of Kassel, we are part of the mFund project MOTUS, which we would like to introduce to you in more detail below.

CHAPTER 1: Max Bäumler from TU Dresden

Hello Max, would you like to briefly introduce yourself and your research?

My name is Maximilian Bäumler, I'm 30 years old and I'm researching the prediction of accidents at junctions within MOTUS at TU Dresden.

How did the MOTUS project originate?

Thank you for the question, Lara!

I think it's super exciting to start by looking at how the idea of MOTUS came about.

I remember it was just at the beginning of the pandemic, the first lockdown in 2020, and we had seen, here at TUD, that traffic behavior had changed drastically. The streets were suddenly empty, you didn't see any cars, there were fewer pedestrians on the road and, independently of each other, several faculties thought that they absolutely had to record and investigate this. In other words, the traffic psychologists started conducting surveys on the change in mobility behavior and we at the LKT, for example, also carried out video observations and filmed intersections to see what traffic behavior looked like. And after we got together at some point because we realized that we had recorded all the data and we needed to bring it together, we said let's do the MOTUS project together and let's investigate what actually happens during disruptive events like a pandemic and how these events affect traffic patterns in cities.

What does the abbreviation MOTUS actually stand for?

What does MOTUS actually stand for? MOTUS is Latin and means movement. And within our project, we practically used MOTUS to form an acronym, namely from the words: MOTUS - MObilityTransformation: Insights into key factors for sUstainable and reSilient transportation. Ultimately, the acronym from MOTUS is not immediately obvious, so just remember that MOTUS means movement and our project is about movement and transport.

And how exactly does the MOTUS project aim to achieve this?

In a nutshell, MOTUS is about the fact that we should have sustainable and resilient transportation systems in cities in the future, or especially in the future. What does that mean in specific terms?

We want to make it possible or, above all, we want to enable municipalities to take precautions now so that no matter what happens in the future, whether it is a climate change event, another pandemic or structural change, their transportation system in their city is sustainable and resilient. And, above all, remains so.

Resilient here means above all resistance, i.e. if we now imagine a city and how transport works in this city, with public transport (buses and trains), with bicycle traffic and also with car traffic, then we would like to be able to develop recommendations now for municipalities and mayors so that they can take precautions if another pandemic occurs so that transport is still sustainable.

This means, for example, that in the next pandemic, as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic, people might initially avoid public transport and switch to cars out of fear of catching the virus. And that could hypothetically mean - we haven't proven it yet - that switching to cars would result in more CO2 emissions or more accidents involving cars. And this is not sustainable in our view, but rather counterproductive.

And now it would be interesting to know what actions a municipality would have to take to prevent exactly this in the next pandemic, e.g. increasing the number of public transport services, disinfecting or sensitizing people to the fact that if you behave in this way, you don't have to be afraid of infection.

And the interesting thing is, in MOTUS we don't just want to look at pandemics, we want to say in general how you can prepare for disruptive events. And we thought we would look at climate change and pandemics or future pandemics, as well as disruptive events such as structural change in brown coal regions.

All of these things can turn a transport system completely upside down - from one day to the next or even in the long term - and that's why it's interesting to consider now what you can do as a municipality to ensure that your system is sustainable and resilient despite these events.

And how does MOTUS want to achieve this?

Now we have a really big goal in MOTUS and the question is, of course, how do we manage to develop these measures for the municipalities so that they know what they can do to ensure that their transport system is and remains sustainable in the future.

And for this we would like to have a simulation platform at the end, i.e. you can imagine that you open our platform and then you can run through various scenarios, such as climate change or pandemic scenarios or structural change scenarios, and then you get a recommendation on what measures you should take to ensure that the transport system remains sustainable and resilient.

And this simulation platform is based on a model and this model is structured like a control loop. In other words, we first look at how traffic in a city looks in abstract terms, how users behave, how users drive through the city and how they move and how many accidents happen, evaluate the whole thing, then consider whether the whole thing is already sustainable or whether it is even less sustainable and if, for example, it turns out that it is less sustainable at the moment, then we would say that we need to take measures to improve this system. Then we implement these measures and look again at how the individual models perform.

And perhaps broken down again in more detail, so you can imagine how it works: Our main model is like a staircase:

At the very beginning is the mobility behavior model, in this we look at what the user preference is, i.e. where do users want to travel to in the first place, why do they want to travel through our city and which mode of transport do they want to use?

In our second model, the transportation demand and traffic flow model (difficult name), we then look at how users move through our abstract city. In other words, where exactly do they go? Which exact road do they take with their vehicle, e.g. by car or by bicycle?

And then comes our safety risk model, which means we zoom in even deeper and look at how many accidents occur at individual intersections, depending on which road users are on the road and how they move through the city.

And at the end, we take the results of all these models, which are arranged like a staircase, and try to evaluate the whole thing. So are a lot of accidents happening now? Are there a lot of CO2 emissions, for example because there are a lot of cars on the road or not, then we work out an assessment score for sustainability and resilience and then decide what measures need to be taken. And at the same time - we can now look at this process for the normal case - and we will also look at this process for disruptive events, such as the pandemic, climate and structural change, and then consider again: How does this and that variable change depending on our disruptive event? And in the following, we will give you an insight into how these individual models are supposed to work.

Now that you've introduced us to the project, would you like to tell us a bit more about what you're working on in the project?

My job is to model the last model in the staircase that we have already heard about today in the staircase of models. This is the accident prediction or safety risk model. In other words, in my area of responsibility, in my research, we zoom in on specific nodes in our simulation and consider which accidents and how many accidents per year would now occur in a given disruptive scenario or even in a normal state, and we then report precisely this figure to the evaluation unit, which can then assess whether the transport system is sustainable and resilient. To model the whole thing, we look at how the vehicles drive, how they interact with each other, how the road users interact with each other, try to describe the whole thing and then build an accident prediction model based on extreme values.

CHAPTER 2: Paul Papendieck from the University of Kassel

Paul Papendieck is primarily responsible for the mobility behavior model in MOTUS. Paul is a traffic psychologist at the University of Kassel and is responsible for MOTUS at the Institute of Transportation. Paul, what exactly is a disruptive event?

Basically, the word disruptive can be translated as “interrupting” in the context of traffic research. So we want to look at how certain events disrupt normal everyday habits in road traffic. As Max has already mentioned, the COVID-19 pandemic was a prime example of a disruptive event: Suddenly some external thing happens, some virus, and that makes me suddenly think about whether I should avoid public transport for the time being and switch to my bike or car to get to work. Or maybe I'm traveling less to work because my employer has introduced home office regulations - and so on and so forth. This means that the entire transport system, i.e. the interplay between the different modes of transport on the roads, railways and paths in a city, is suddenly mixed up.

And we want to find out what other events there are that can upset the interplay and, above all, how we can design traffic systems that can cope with this, i.e. that do not immediately sink into traffic jams and chaos because the established mechanisms have been disturbed. In the context of MOTUS, we are thinking, for example, of extreme weather events in the course of climate change, structural changes in a location and so on.

What do you mean by structural changes in a place?

An example of this could be places that are affected by the structural change brought about by the energy transition. There are some places in Germany, for example, that are very strongly characterized by the fact that brown coal mining takes place locally. Now that Germany wants to move away from lignite, these places will inevitably experience major changes in the near future or are already doing so. Routes to work will change, there may be major infrastructure projects, a changing cultural offering, and so on. And all of this naturally has an influence on how people travel in these regions, what destinations they have and who is on the move at all. In recent decades, there have been structural changes of this kind in the Ruhr region, for example.

Ha, that's exciting! And where do you come into this now?

As a traffic psychologist, I'm naturally most interested in the behavior of individual road users: How do they travel, what means of transport do they use, what are their destinations and how do they change their behavior when a disruptive event occurs? Max has already mentioned that the first step in the project is the mobility behavior model and that is exactly what I am responsible for.

Can you describe this mobility behavior model in more detail?

We are planning a large-scale survey for MOTUS that will record individual traffic behavior. To do this, we have designed an online survey in which a total of 15,000 people from Dresden and our two model municipalities Bad Hersfeld and Leipzig are asked to complete a questionnaire about their traffic habits. Of course, we also welcome participants from all other regions of Germany. In this questionnaire, we firstly record the participants' everyday transport habits, i.e. “what destinations do they have in everyday life” and “what means of transport do they use”. On the other hand, we also ask whether people have ever experienced disruptive events that have changed their transportation habits. We then use this information to calculate typical behavioral patterns of how certain groups of people react to certain types of events. This could be something like: Young people under 28 are more likely to switch to bicycles if the bus or train is canceled, while people over 35 are more likely to switch to cars. In other words, something like age could play a role here, just as an example, but personality traits can also be important, income brackets, occupational groups, whether people live in the country or in big cities, and so on. And we then pass this information on to Angelika and Andreas, who process it for the transport demand and traffic flow model.

However, this is not the only information that is generated in the mobility behavior model - you, Lara, also have an important role to play with Teralytics. Tell us about it!

CHAPTER 3: Lara Efinger from Teralytics

Yes, of course, I'd love to.

At Teralytics, we use mobile phone data to create a wide range of analyses on people's mobility. In Germany, we use Telefónica data for this, which we extrapolate to the total population using regional market shares.

It is often assumed that we receive the direct location data from the SIM cards and can then convert this directly into movement profiles. Unfortunately, it is not quite that simple, as we only receive the connection data of the SIM cards with the mobile phone masts. These are not even triggered that often,

only every few minutes on average. In addition, the data contains many skews, which we first have to correct through evaluations and conversions, for which we use machine learning, among other things. Fortunately, we now have over 10 years of experience, which is why we can regularly update our data sets with improved quality and introduce new products.

In the MOTUS project, we provide our data set “Matrix Short Distance”. Here we have a fine-grained zoning with regard to the infrastructure of the mobile phone masts, with which the traffic areas of the model municipalities selected in the project can also be analyzed very well.

The data in the matrix data set are classic origin-destination matrices, which output the travel behavior of group movements. With regard to German data protection regulations, we are only allowed to output data if more than 5 extrapolated people have made a trip. A trip is defined in such a way that the SIM card must have been at the start or destination for at least 30 minutes. The travel route is not taken into account and is not included in the data. In addition to the fine zoning, this procedure also allows us to output the data on an hourly basis. The weekdays of a month are added together so that enough interdependencies reach the limit value of 5. We therefore add up all Mondays, Tuesdays etc. in the month. This makes it possible, for example, to evaluate the travel data for a typical Monday in December.

Within the MOTUS project, we would now like to research how we can break down the data even more granularly. Specifically, this will involve the reliable detection of transportation modes. In our Matrix long-distance data set, we can already differentiate between road, rail and plane from a travel distance of 30 km. We now want to take this to the next level and also make it possible for journeys of less than 30 km. We hope to achieve this by using a new calculation method for travel routes and incorporating a wide range of comparative data. The first step will be to examine smaller regions, but the ultimate goal is of course to be able to offer the breakdown in our matrix data sets for all regions and countries.

CHAPTER 4: Angelika Hirrle from the TU Dresden

Next, we would like to introduce you to Angelika.

Dr. Angelika Hirrle is a research assistant at the Chair of Traffic Process Automation at TU Dresden.

Angelika, you are developing the demand and traffic flow model in the MOTUS project. What exactly does that describe?

This model is embedded between the mobility behavior model that Paul is developing and Max's safety risk model. While Paul investigates how people's mobility behavior changes during disruptive events, we want to understand how this changed behavior affects urban mobility and traffic. To do this, we first take a bird's eye view and look at traffic flows in the city. We then zoom into these traffic flows at various intersections and look at the individual road users in the flows. Max then looks at the interaction of these road users in his safety risk model.

How exactly can we imagine this model?

The model is based on the collection and analysis of a large amount of data. This data can be divided into different categories. On the one hand, we use data that describes the topology of a city, for example the transport network with roads, intersections, cycle paths and public transport infrastructure. But it also includes buildings and their functions such as schools, shopping centers and museums. Secondly, we use data that describes the dynamics, i.e. the movement of people in the city. These are, for example, origin-destination correlations, which are derived from mobile phone data and fed into our project by Teralytics. But we also use information on traffic flow, such as that obtained from mobile or fixed counting stations, if it is available. And the third major category is socio-demographic data. This includes information on people such as age, gender, educational background, but also travel routes and reasons. This type of information is available in open city databases or is obtained in surveys.

We analyze this data and build simulations. The simulations have the advantage that we can run through various scenarios that do not exist in reality. We can use models to consider what would happen under certain boundary conditions and can thus investigate which disruptive events trigger which dynamics and what impact certain measures have.

Are these models generally valid or do they only apply to a specific city or region?

The aim is to be able to make generally valid statements about mobility in cities. By evaluating and linking all the data and simulations, we want to understand how the topological structure of a city and the dynamics within it interact and which socio-demographic factors have a decisive influence. For example, it is reasonable to assume that the movement patterns of certain user groups will depend on how heterogeneous, i.e. dispersed, their destinations are in the urban area - think, for example, of commuter flows, which will naturally depend on the number and location of workplaces. But the design of the range of shopping and leisure facilities will also influence the dynamics.

The MOTUS project is about identifying key factors for resilient and sustainable mobility. How can we imagine the use of these in your model?

If we know the relationship between the topological structure of a city, the dynamics within it and socio-demographic factors, we can then also derive statements on how the sustainability and resilience of a city are linked to people's mobility.

The aim is to understand how the dynamics change in the event of disruptive events, what the main parameters are that cause these changes and how these changes can be predicted based on very specific topological and socio-demographic factors. This is the basis for considering what measures should be taken to influence a particular dynamic. For example, how should public transport services be changed to ensure sustainable mobility? How must the urban transport system be designed to be robust in the face of disruption? And how must the topology of the city, but also the mobility offer, be designed so that it is perceived as senior- or family-friendly, for example?

CHAPTER 5: Julia Gerlach from TU Dresden

The graduate engineer Julia Gerlach is also from TU Dresden and works as a research assistant at the Chair of Transport Ecology.

Julia, you are responsible for sustainability assessment in the project. What does sustainability actually mean?

Well, there is this famous definition of sustainable development from the Brundtland Report, which states that sustainable development is development that meets people's needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

For the transport sector, this means that we have to design the transport system in such a way that people can carry out their activities without any problems, that they can be mobile and reach their destinations, but also that it has to be environmentally friendly so that we do not take away the basis of life from our children and grandchildren, for example, through excessive consumption of resources, our CO2 emissions or similar.

So the project examines how climate-friendly people are on the road?

Yes, exactly! The level of CO2 emissions in transportation is a decisive factor for sustainable development.

But that is not the only relevant effect. Sustainability is based on three pillars: environment, economy and social issues. And we also look at traffic noise and emissions of air pollutants in the environmental area.

From an economic point of view, it is primarily about the costs that are incurred, for example, for the maintenance of the transport infrastructure or the operation of buses and trains. In terms of social impacts, we then assess road safety, for example.

A target is formulated for each of these impacts, e.g. in the area of climate protection based on the German Climate Protection Act. This says that we want Germany to be climate-neutral by 2045. And we can then assess how well we are on track for each individual target. And finally, we combine these individual assessments into an overall assessment. This then changes depending on which scenarios or countermeasures for a pandemic etc. are modeled.

Closing words:

Many thanks Julia and also many thanks again to Max, Paul and Angelika for presenting your work packages in the MOTUS project. Many thanks also to everyone who has listened/ read ;) up to this point. We hope that we have been able to give you an understanding of our project and would be delighted if you tuned in again when we are able to present the results of our project. See you again!

Termine / Veröffentlichungen

- Papendieck, P., Bäumler, M., Sotnikova, A., Hirrle, A. (2022). Learning from Covid: How can we predict mobility behaviour in the face of disruptive events? - How to investigate the mobility of the future. 4th Symposium on Management of Future Motorway and Urban Traffic Systems (MFTS), Dresden, Germany.

- Bäumler, M., Lehmann, M., Prokop, G. (2023). Generating representative test scenarios: The fuse for representativity (Fuse4Rep) pocess model for collecting and analysing traffic observation data. 27th ESV conference 2023, Yokohama, Japan.

- Papendieck, P. & Francke, A. (2023). Neue Wege aus der Gewohnheitsfalle: Identifikation von Faktoren für den bewussten Wechsel auf das Fahrrad. 8. Nationaler Radverkehrskongress, Frankfurt, Deutschland.

- Papendieck, P. & Francke, A. (2023). How can cycling mitigate the impact of disruptive events on mobility systems? Velo-city 2023, Leipzig, Germany.

Veröffentlichte Datensätze

- Repräsentative Drohnendatensätze (3 Monate)

Problemstellung

Disruptive Ereignisse ändern Verhaltensweisen. So stellte bspw. die Corona-Pandemie den Alltag und somit auch das Mobilitätsverhalten vieler Menschen auf den Kopf: Gewohnte Wege entfielen und neue Verkehrsmittel, wie das Fahrrad, kamen auch aufgrund von Sorgen vor Ansteckung im ÖPNV, hinzu. Wie langfristig die Änderungen sowie die Auswirkungen auf die Nachhaltigkeit und Resilienz (Widerstandsfähigkeit) bestehender Verkehrssysteme sein werden, ist unklar. Sicher hingegen ist, dass weitere disruptive Ereignisse, wie z.B. der Klima- oder Strukturwandel in Braunkohlerevieren, auftreten werden.

Projektziel

Ziel von MOTUS ist die Entwicklung einer Simulationsplattform, die einen ganzheitlichen Blick auf das urbane Verkehrssystem und dessen Akteure ermöglicht. Somit können Entscheidungsträgerinnen und Entscheidungsträger aus Kommunen Präventivmaßnahmen für zukünftige disruptive Ereignisse ableiten und gezielt vorsorgen. In der Plattform werden dabei sowohl die Nachhaltigkeit als auch die Resilienz eines urbanen Verkehrssystems berücksichtigt. Ein spezielles Augenmerk wird hierbei auf die Corona-Pandemie, den Klima- und den Strukturwandel in Braunkohlerevieren gerichtet.

Die Grundlage für das in der Simulationsplattform hinterlegte Modell bilden dabei Mobilfunk-, Drohnen-, Detektor-, Unfall- und Befragungsdaten vor, während und nach der Corona-Pandemie.

MOTUS möchte dabei die folgenden Parteien wie folgt unterstützen:

- Kommunale Entscheidungsträger:innen:

- Förderung Systemverständnis.

- Unterstützung bei Entscheidungen, z.B. hinsichtlich Nachhaltigkeitswirkung.

- Kommunale Verkehrsplanung:

- Unterstützung Verkehrsentwicklungsplanung, z.B. durch einen Maßnahmenkatalog.

- Neubewertung bestehender Pläne hinsichtlich Nachhaltigkeit / Resilienz.

- Bereitstellung veredelter Verkehrsdaten.

- Bürger:innen:

- Sensibilisierung für nachhaltigen und resilienten Verkehr, z.B. durch den MOTUS-Podcast.

Forschungsfragen

MOTUS adressiert die folgenden Forschungsfragen:

- Wie verändert sich das Mobilitätsverhalten durch disruptive Ereignisse?

-

Wie wirkt sich das veränderte Mobilitätsverhalten aufgrund disruptiver Ereignisse auf urbane Verkehrssysteme aus?

-

Welche Maßnahmen können ergriffen werden, um Nachhaltigkeit und Resilienz

auch bei zukünftigen disruptiven Ereignissen zu gewährleisten?

-

Wie sind die Ergebnisse aus den Analysen der COVID-19-Pandemie auf andere disruptive Ereignisse, wie Struktur- und Klimawandel, übertragbar?

Methodisches Vorgehen

Die Forschungsfragen sollen in einem interdisziplinären Ansatz zur Modellierung und Steuerung des Verkehrssystems (siehe Regelkreis) beantwortet werden:

- Das Transportmodell umfasst Modelle für Reiseverhalten, Verkehrsnachfrage, Verkehrsfluss und Sicherheitsrisiko. Diese Modelle werden durch Erhebungen, Datenanalyse und Simulation abgeleitet.

- Störende (disruptive) Ereignisse, die das System beeinträchtigen, sind Pandemien, Klimawandel und Strukturwandel. Für jedes Störungsereignis wird eine Reihe von Szenarien untersucht, die durch Variablen aus einer STEEPLE-Analyse des Systems definiert sind.

- Eine Messeinheit ("Bewertungseinheit") bewertet die Nachhaltigkeit und Resilienz des Systems, indem sie mehrere Variablen und deren zeitliches Verhalten auswertet.

- Die Steuerung ("Maßnahmenkataolog") umfasst verschiedene Aktionen und Messungen auf verschiedenen Skalen, je nach der Differenz zwischen der gemessenen Nachhaltigkeit und Resilienz und ihren Referenzwerten.

Modellkommunen

Die MOTUS Simulationsplattform wird im Projektverlauf auf die während des Projektes ausgewählten Modellkommunen Leipzig und Bad Hersfeld übertragen und getestet.

Zeitplan

Projektlaufzeit: 11/2021 – 10/2024

Projektpartner

Die folgenden fünf Projektpartner bilden das MOTUS Projektkonsortium:

| TU Dresden: Professur für Verkehrsprozessautomatisierung (VPA) |

| TU Dresden: Professur für Verkehrsökologie (VÖK) |

| TU Dresden: Lehrstuhl Kraftfahrzeugtechnik (LKT) |

| Universität Kassel: Professur für Rad- und Nahverkehr (RVN) |

| Teralytics GMBH Hürth |

Ansprechpartner

© Axel Gerhard

© Axel Gerhard

Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter

NameHerr Dipl.Ing. (FH) Axel Gerhard M.Sc.

Fahrzeug- und Verkehrssicherheit

Eine verschlüsselte E-Mail über das SecureMail-Portal versenden (nur für TUD-externe Personen).

Besuchsadresse:

Jante-Bau, JAN 22-A George-Bähr-Straße 1b

01069 Dresden