May 18, 2021

Rotating forces get embryos in shape

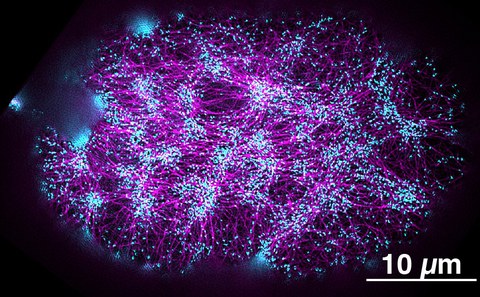

Super-resolution fluorescence image of the actomyosin cortex in a one-cell embryo. The actin filaments are labeled in magenta, and the regions where forces and torques are generated are labeled in cyan.

Dresden researchers discover how a protein creates the rotatory forces essential for animal development.

Our body appearance is symmetric from the outside. If you take a look inside, you will find our organs are not at all arranged symmetrically. The heart, for example, is on our left side. These differences in structure, referred to as left-right asymmetry, emerge very early during the development and are crucial for an embryo to properly grow. Researchers have found in past studies that rotatory forces, so-called torques, play an important role to create the left-right asymmetry, thereby shaping cells and organs. Now, scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the Biotechnology Center of the TU Dresden (BIOTEC), and the Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life (PoL) at the TU Dresden identified the proteins involved in the generation of torques and explained their interaction.

A developing organism needs axes for orientation: Where is the top and the lower part of the body, where the back and the front? A third axis defines where the left and the right side goes. While the outside of our body is overall left-right symmetric, our internal organs are arranged left-right asymmetrically. This left-right asymmetry arises already during the early development of an embryo, and can even be observed within individual embryonic cells. Cellular left-right symmetry breaking depends on the cell cortex – a fine network of actin filaments and myosin motor proteins just below the cell membrane. In response to Myosin motor activity, the cortex undergoes cellular-scale movements, or flows, and sets itself in motion in a collective manner. Interestingly, the cortex undergoes a rotational movement: the opposite halves of embryonic cells rotate in opposite directions. In turn, these opposite rotations cause the tilting of some cells, and thus lead to the breaking of the left-right symmetry of the entire organism. This mechanism was identified in past studies by the research lab of Stephan Grill, who is a director at the MPI-CBG and speaker of PoL.

From physics we know that rotatory movements arise in response to rotatory forces or torques. What was not known so far, is which molecules are responsible for actively generating the rotatory forces that facilitate counter-rotations, and how they do this? The postdoctoral researcher Teije Middelkoop in the group of Stephan Grill worked together with researchers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), USA and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), USA to address this question. Teije Middelkoop suspected that two groups of proteins are involved in creating torques: Formin proteins that help to generate actin filaments and Myosin motor proteins that pull on actin filaments. Because actin filaments are molecular cables with a right-handed helical twist, both these proteins could in principle generate molecular scale rotatory forces, but whether and how these two protein types interact was unclear. Teije Middelkoop explains: “By performing fluorescent confocal microscopy, we found that counter-rotating flows in the cortex of the Caenorhabditis elegans roundworm increased when there was more Formin available. Once we reduced the amount of Formin in the roundworm or removed it completely, we also saw less torques in the cortex.” Moreover, the researchers found out how Myosin and Formin cooperate: While Myosin is required to trigger the necessary cortical movements, analogous to the engine of a car, Formin acts like a steering wheel and ensures that the forces generated by myosin cause rotating flows and cell movements.

Stephan Grill summarizes: “These findings are another example of bridging physics and biology that has long been done in an ideal way here in Dresden. We have biologists and theoretical physicists on campus who are able to provide an interdisciplinary approach to the physics of biological processes. And the exciting thing about this study is that we now understand the physical forces and torques underlying embryonic growth a bit better.”

Original Publication:

Teije C. Middelkoop, Júlia Garcia-Baucells, Porfirio Quintero-Cadena, Lokesh G. Pimpale, Shahrzad Yazdi, Paul W. Sternberg, Peter Gross, and Stephan W. Grill: CYK-1/Formin activation in cortical RhoA signaling centers promotes organismal left–right symmetry breaking. PNAS 18. May 2021

Doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021814118

Media contact MPI-CBG

Katrin Boes

+49 (0) 351 210 2080

Further information:

Prof. Stephan Grill

About the MPI-CBG

The Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), located in Dresden, is one of more than 80 institutes of the Max Planck Society, an independent, non-profit organization in Germany. 550 curiosity-driven scientists from over 50 countries ask: How do cells form tissues? The basic research programs of the MPI-CBG span multiple scales of magnitude, from molecular assemblies to organelles, cells, tissues, organs, and organisms. The MPI-CBG invests extensively in Services and Facilities to allow research scientists shared access to sophisticated and expensive technologies.

www.mpi-cbg.de

About PoL

The Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life (PoL) at TU Dresden focuses on the laws of physics that underlie the organisation of life into molecules, cells and tissues. At the cluster, physicists, biologists and computer scientists join forces to investigate how active matter organises itself into predetermined structures in cells and tissues, thus giving rise to life. PoL is funded by the DFG as part of the Excellence Strategy. It is a collaboration between scientists from TU Dresden and research institutions of the DRESDEN-concept network, such as the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPI-PKS), the Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research (IPF) and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR).

www.physics-of-life.tu-dresden.de

About the Biotechnology Center of the TU Dresden

The Biotechnology Center (BIOTEC) was founded in 2000 as a central scientific unit of the TU Dresden with the goal of combining modern approaches in molecular and cell biology with the traditionally strong engineering in Dresden. Since 2016, the BIOTEC is part of the central scientific unit “Center for Molecular and Cellular Bioengineering” (CMCB) of the TU Dresden. The BIOTEC is fostering developments in research and teaching within the Molecular Bioengineering research field and combines approaches in cell biology, biophysics and bioinformatics. It plays a central role within the research priority area Health Sciences, Biomedicine and Bioengineering of the TU Dresden.

www.tu-dresden.de/cmcb/biotec

www.tu-dresden.de/cmcb