lecture series

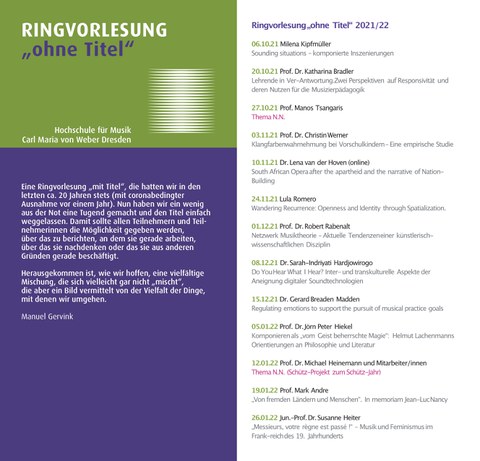

Ringvorlesung "Ohne Titel", gemeinsam mit der HfM Dresden (WS 21/22)

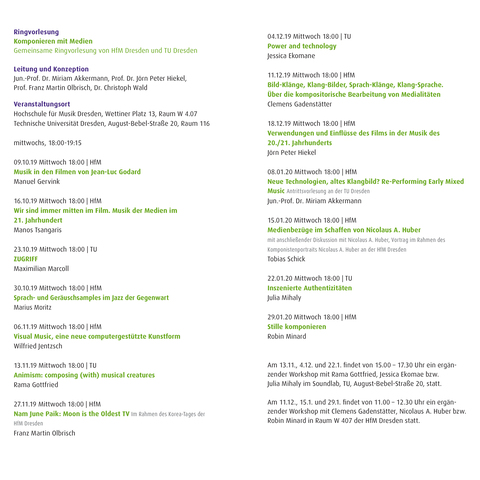

Ringvorlesung "Komponieren mit Medien", gemeinsam mit der HfM Dresden (WS 19/20)

Ringvorlesung "Aktuelle Perspektiven der Klangforschung" (WS 17/18)

Ringvorlesung "Music Perception and Cognition" (WS 16/17)

Ringvorlesung "Music Perception and Cognition" (WS 15/16)

Ringvorlesung "Ohne Titel", gemeinsam mit der HfM Dresden (WS 21/22)

Ringvorlesung "Komponieren mit Medien", gemeinsam mit der HfM Dresden (WS 19/20)

Ringvorlesung "Aktuelle Perspektiven der Klangforschung" (WS 17/18)

| Datum | Referent_In | Titel |

| 17. Oktober | Florian Zwißler (Köln) |

"Eine neue Dimension für das musikalische Erlebnis": Der Klangraum als Parameter im kompositorischen Schaffen Karlheinz Stockhausens |

| 24. Oktober | Ercan Altinsoy | Klang des Lebens und Produktgeräusche |

| 7. November | Christoph Wald | Die verzerrte Gitarre und der "eigene Sound" |

| 14. November | Holger Schwetter |

Environment, Sound, Performance, Tanz? Musik-Erleben in der Rockdiskothek |

| 21, November | Marc Bangert (Karlsruhe) |

Fake Sounds - Das musikalische Ohr als Inferenzmaschine |

| 28. November | Jan Hemming (Kassel) |

Soundscapes. Der Weihnachtsmarkt als Klangquelle |

| 5. Dezember | Anna Schürmer |

NOISE – INTERFERENZEN – INTERPOLATIONEN: Die Musikalisierung von Störgeräuschen, oder: Musik- als Medienwissenschaft |

| 9. Januar | Sebastian Biesold (Bonn) |

Biografie- als Klangforschung am Beispiel der Sächsischen Staatskapelle Dresden |

| 16. Januar | Barbara Wiermann |

Klangwelt und Inszenierung des Grammophons |

| 23. Januar | Karlheinz Brandenburg (Ilmenau) |

Der Traum vom perfekten Klang: High Fidelity von Edison bis heute |

| 30. Januar | Christian Thorau (Potsdam) |

Musikwissenschaft als Hörgeschichte |

Ringvorlesung WS 2016/17

Warum fühlt sich die Spezies Mensch so sehr von Musik angezogen und welches sind die Gemeinsamkeiten der unterschiedlichen musikalischen Ausdrucksweisen, die von Kulturen überall in der Welt kreiert worden sind? Welche Formen nimmt Musik an, um Performance und Tanz zu ermöglichen und was genau macht diese Aktivitäten eigentlich so angenehm? Warum fühlt sich Musik, die wir uns im Kopf vorstellen, so wirklich an und wie kommt es, dass unser Gehirn diese Meisterleistung überhaupt erbringen kann?

Die Ringvorlesung “Systematic Musicology: Perception and Cognition of Music”, organisiert vom 2015 gegründeten Dresden Music Cognition Lab (DMCL) der TU Dresden, beleuchtet diese und weitere Fragen.

In zwölf unabhängigen Vorträgen beschäftigen sich internationale Wissenschaftler mit den Phänomenen Musik und Musikwahrnehmung anhand aktueller Forschungsfragen aus diversen interdisziplinären Perspektiven von Musiktheorie, experimenteller Psychologie, kognitiven Neurowissenschaften, bishin zu Evolutionstheorie und Informatik.

Die Vorlesungsreihe richtet sich an ein breites Publikum und setzt wenig Vorkenntnisse voraus. Die Referenten geben eine Einführung in Ihr Fachgebiet und bieten einen Einblick in aktuelle Forschungsergebnisse.

Vortragende und Themen

| Datum | Referent | Titel des Vortrages |

|---|---|---|

| 11.10.2016 | Henkjan Honing (University of Amsterdam) |

What makes us musical animals |

|

Abstract Over the years it has become clear that all humans share a predisposition for music, just like we all have a capacity for language. This view is supported by a growing body of research ranging from the pioneering work of developmental psychologists Sandra Trehub and Laurel Trainor to that of neuroscientists such as Isabelle Peretz and Robert Zatorre. These studies also indicate that our capacity for music has an intimate relationship with our cognition and underlying biology, which is particularly clear when the focus is on perception rather than production.

2. Winkler I, Háden GP, Ladinig O, Sziller I, Honing H (2009) Newborn infants detect the beat in music. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 2468–2471. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809035106. 3. Honing H (2012) Without it no music: beat induction as a fundamental musical trait. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1252: 85–91. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06402.x. 4. Merchant H, Honing H (2014) Are non-human primates capable of rhythmic entrainment? Evidence for the gradual audiomotor evolution hypothesis. Front Audit Cogn Neurosci 7: 1–8. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00274. 5. Honing H, Merchant H, Háden GP, Prado L, Bartolo R (2012) Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) detect rhythmic groups in music, but not the beat. PLoS One 7: 1–10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051369. 6. van der Aa J, Honing H, ten Cate C (2015) The perception of regularity in an isochronous stimulus in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) and humans. Behav Processes 115: 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2015.02.018. 7. ten Cate C, Spierings M, Hubert J, Honing H (2016) Can birds perceive rhythmic patterns? A review and experiments on a songbird and a parrot species. Front Psychol 7: 1–14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00730. |

||

| 25.10.2016 |

Daniela Sammler (Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig) |

Motor planning in expert pianists – the special role of musical syntax Vortragsfolien (PDF) |

|

Abstract Over the past 20 years, research on the neurocognition of music has gained a lot of insights into how the brain perceives music. Yet, our knowledge about the neural mechanisms of music production remains sparse. One aspect that has been studied particularly well in perception is musical syntax, i.e. the processing of harmonic rules in the auditory signal. The present talk will demonstrate that the notion of syntax not only applies to the auditory modality but transfers – in trained musicians – to a “grammar of musical action”. I will present a series of neuroimaging experiments that show (i) that the performance of musicians is guided by their music-syntactic knowledge – irrespective of sounds, (ii) that syntax takes priority over the selection of finger movements during piano performance, (iii) that training style (classical vs. Jazz) has an impact on syntactic motor planning, and (iv) that syntax perception and production in music overlap partly – but not fully – in the musician’s brain. Altogether, these results show how strongly musicians rely on syntax as a scaffolding that facilitates their performance and enables them to achieve the motoric proficiency that is required on stage. |

||

|

01.11.2016 |

Subhendu Ghosh (Hindustani Classical vocalist, dramatist, music director, cultural and social activist) see note (*) below |

Cultural Identity and Cross Border Musical Heritage: The Bengal Experience |

|

Abstract When British Government divided Bengal in 1905, the intelligentsia took to the streets. People like Rabindranath Tagore sang against the division of Bengal and the poetry and music as described above kept different religious communities together. In 1947 the partition of Bengal added to the discomfort of people from both eastern and western parts. Despite the fact that East Bengal remains politically separated from the west (Bengal) it has been successful in upholding the Musical Heritage, the traditions of Bauls, Bhatali and other imbibed Classical, Semi-Classical music. In this paper I am going to discuss how the people of Bengal have achieved this. _____________ * N.B.: This event is part of the "Structure, Culture, and Cognition in Cross-Cultural Music Research" workshop, the full schedule of which you can find here |

||

| 08.11.2016 | Tecumseh Fitch (University of Vienna) | What is music, that it moves us? Vortragsfolien (PDF) |

|

Abstract |

||

| 22.11.2016 | Rie Asano (University of Cologne)* |

Syntax in Music and Language: A Comparative Approach and Action-Oriented Perspective |

|

Abstract It is often claimed that music and language share a process of hierarchical structure building, a mental “syntax.” Although several lines of research point to commonalities, and possibly a shared syntactic component of music and language, differences between “language syntax” and “music syntax” can also be found at several levels: conveyed meaning and the atoms of combination, for example. Instead of comparing syntax in language and music some researchers have suggested a comparison between music and phonology (“phonological syntax”), but here too, one quickly arrives at a situation of intriguing similarities and obvious differences. In this talk, I suggest different comparative approach to go beyond such a shared/distinct dichotomy in comparing language and musical “syntax” and “phonology”. First, I show that the similarity of syntax in music and language lies in the fact that hierarchically structured representations are mapped onto temporal sequences or vice versa, i.e. the problem of linearization and structure building. Second, I claim that a fruitful comparison between these two cognitive domains can benefit from taking action syntax, i.e. a grammar of action, into account. I will end with an application of the action-oriented perspective to music in the domain of rhythmic syntax, and conclude that research on rhythmic syntax – till now a neglected aspect of musical syntax – is necessary to reveal the mysterious relationship between music and language from a theoretical, psychological, neuroscientific, and evolutionary perspective. _____________ * N.B.: Please note this talk replaces the originally-scheduled one by Elaine Chew, which the speaker has had to cancel due to personal reasons. |

||

| 29.11.2016 |

Iain Morley (University of Oxford) __________

|

Without a song or a dance what are we? Multi-disciplinary approaches to the prehistory of music __________ Our path to music and language: the vocal learning bottleneck and the powers of cultural transmission |

|

Abstract (Iain Morley) Archaeological evidence for musical activities pre-dates even the earliest-known cave art and no human culture has yet been encountered that does not practise some recognisably musical activity. Yet the human abilities to make and appreciate music have been described as “amongst the most mysterious with which [we are] endowed” (Charles Darwin, 1872) and music itself as “the supreme mystery of the science of man” (Claude Levi-Strauss, 1970). Unlike the evolution of human language abilities, it is only recently that the origins of musical capacities have begun to receive dedicated attention, and much has remained mysterious about this ubiquitous human phenomenon, not least its prehistoric origins. No single field of investigation can address the wide range of issues relevant to answering the question of music’s origins. This talk brings together evidence from a wide range of anthropological and human sciences, including palaeoanthropology, archaeology, neuroscience, primatology and developmental psychology, in an attempt to elucidate the nature of the foundations of music, how they have evolved, and how they are related to capabilities underlying other important human behaviours.

He has carried out archaeological excavation work in Britain, Croatia, Moravia (Czech Republic), Italy, Greece and Libya; he is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, and is based at the University of Oxford in the School of Anthropology & Museum Ethnography. ____________________________________________ Abstract (Bjorn Merker) Imagine a population in which each member expresses their cognitive contents by means of strings of syllables, one string per content, randomly generated for each content, and independently so for each individual. There would, of course be utter and total mutual incomprension among members of such a population. Imagine then that someone told you that if each member of this population simply repeated what they heard and remembered of the incomprehensible utterances of others and repeated this to their offspring, the nonsense babbling of this population would over generations converge on a population-wide shared vocabulary and efficient grammar, and this without a trace of Darwinian selection or differential reinforcement of outcomes. You might think the claim to be preposterous, but you would be wrong, as demonstrated by computer simulations of just such populations of learning agents by Simon Kirby and colleagues at Edinburgh. In my presentation I will explain the mechanism behind this apparently miraculous power of pure cultural transmission, and explore its implications for our conception of the origins of music and language. I will do so by outlining how so called vocal production learning, a specialized capacity spottily distributed across the animal kingdom, supplies a mechanism for implementing the iterated learning paradigm in nature rather than in silico. Having done so, I will suggest that this paradigm explicating the formal powers of purely cultural transmission supplies the key to the consilience of the humanities and the natural sciences by disclosing the inner workings of cultural traditions. N.B.: for more details of this event, please see English version of page |

||

| 06.12.2016 | Eric Clarke (University of Oxford) | Music, empathy and ‘virtual worlds' Vortragsfolien (PDF) |

|

Abstract |

||

| 13.12.2016 | Daniele Schoen (University of Marseille) | Music to speech entrainment Vortragsfolien (PDF) |

|

Abstract |

||

| 10.01.2017 | Reinhard Kopiez (Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien, Hannover) |

The audio-visual music performer: Intermodal interactions in evaluation processes |

|

Abstract The visual component of music performance as experienced in a live concert is of central importance for the appreciation of music performance. However, up until now the influence of the visual component on the audience’s evaluation of music performance has been investigated unsystematically. I will start with some historical examples to demonstrate the visual modality as an integral part of music performance over centuries. Reports on concerts of famous virtuosos of the 19th century such as Franz Liszt are a comprehensive source. These descriptions raise two questions: First, how can the influence of the visual component on music evaluation processes be quantified? Second, which theoretical model could give an explanation for potential evaluation differences? Musical examples from classical and popular music will demonstrate possible methods for providing an answer to both questions. |

||

| 17.01.2017 | Wolfgang Auhagen (Martin Luther Universität, Halle-Wittenberg) |

“As time goes by” - Perception of tempo and time in music |

|

Abstract Starting point of the lecture is W. R. Talsma’s theory of a „metric“ interpretation of historical metronome marks. This theory postulates that today’s performances of compositions from the late 18th and early 19th centuries are wrong: fast movements are performed twice as fast as they were intended, because of a rapid change of time perception in the 19th century as a consequence of industrialization. This theory raises a lot of questions which will be discussed in the lecture. With respect to time perception in music, the question is whether changes in technical processes, in transport techniques etc. really changed tempo in music. If so, why was this change never discussed in books on music theory or musical practice? It can be shown that Talsma’s theory is wrong and that differences in the choice of tempi between performances of the 19th and 20th century derive from different interpretations of the expressive character of the compositions. The second part of the lecture deals with experiments and theories on (musical) time perception. Not only conductors and performers of music can develop precise ideas of performance tempi and keep them in mind but also listeners, even if the music is unfamiliar to them. This corroborates theories of internal „clocks“ in the human brain, developed e.g. by Ernst Pöppel. However, other empirical data show strong contextual influences on time perception in music, especially on perception of rhythm and long term durations. The theory of embodied cognition links human thinking and emotions to bodily experiences and seems to be good framework for the explanation of phenomena in musical time perception. |

||

| 24.01.2017 | Tudor Popescu (TU Dresden) | The consonances we hear, the music we imagine Vortragsfolien (PDF) |

|

Abstract What makes our experience of music possible – and effortless – is an intricate puzzle of cognitive processes, involving a subtle interplay of what psychologists refer to as bottom-up and top-down components. The key concept of expectation can be construed at the centre of a complex feedback loop between these components, relaying information in both directions, and at different time scales. This framework holds not just for music we hear (an exogenous/bottom-up process) but also for music we create in our minds (endogenous/top-down). One mode of acquiring musical knowledge is implicit learning, which gradually gets to shape our sensory preferences, e.g. for certain combinations of simultaneous notes over others (consonant over dissonant chords – or indeed, in some contexts, vice-versa!), and also our unfolding expectations relating to e.g. what musical event might come next. These expectations form the core of a set of intuitions that have been formalised as models of musical structure, most notably Schenkerian analysis. Such models can inspire quantifiable predictions about the temporal nature of our expectation – for instance, with regards to the moment in time when we feel a piece is "beginning to end". The sum of these intuitions endows us with a template that on the one hand enables us to make sense of music that we hear; but equally, also to (re)create music in our own minds – a process known as musical imagery, which shares commonalities with music perception not only at the cognitive level (e.g. both can be conjectured to stem from a single generative model) but also at the neuronal level. In this talk, I will describe three distinct studies from the Dresden Music Cognition Lab, that address – using behavioural and neuroimaging methods – individual elements of the expectation-mediated loop outlined above, namely (i) the (local) perception of consonance and dissonance; (ii) the (non-local) perception of hierarchical musical structures; and (iii) the role of harmonic function in imagined music. I will then attempt to integrate these findings into the larger questions of how expectation guides our listening and imagery of music, and how the brain is wired to make these processes run smoothly in the background. |

||

| 31.01.2017 | Maria Witek (Aarhus University) | Getting into the groove: Pleasure and body-movement in music Vortragsfolien (PDF) |

|

Abstract |

||

Die Finanzierung des Zukunftskonzeptes der TU Dresden erfolgt aus Mitteln der Exzellenzinitiative des Bundes und der Länder.

Ringvorlesung WS 2015/16

Why does music exist and what does it tell us about human cognition? Why do we enjoy listening to sad music? By what means are music and language related? How does film-music manipulate our attention and emotion?

The lecture series “Systematic Musicology: Perception and Cognition of Music”, organised by the recently founded Dresden Music Cognition Lab (DMCL), aims to shed light on these and further questions. International scholars address the phenonenon of music and music perception in twelve stand-alone lectures on the basis of latest research findings from interdisciplinary perspectives such as music theory, experimental psychology, cognitive neurosciences, evolution theory and informatics.

The lecture series is intended for a wide audience and assumes little specialist knowledge. Most speakers will provide an introductory background and then progress to present current state-of-the-art research.

Students of TU Dresden can - as part of the AQUA programme - receive two CPs for attending at least 10 of the total of 12 talks, as well as one additional CP if choosing to take an oral examination at the end of the series. Details will be explained during the lecture series.

Any changes and further announcements can be found here on this page and www.facebook.com/DresdenMusicCognitionLab. For any questions or comments, please contact Dr. Tudor Popescu or Ms. Carolin Thiele by email (both Firstname.Lastname@tu-dresden.de).

We look forward to welcoming you to this interdisciplinary and international lecure series!

| type: | public lecture series / AQUA |

| scope: | 2 SWS |

| time: | Tuesdays, 18:30 – 20:00 |

| place: | Institute of Art and Music, August-Bebel-Str. 20, Room E08 lecture on 12th May 2015 – von Gerber Bau, Bergstr. 53, Room 038 -> campus map |

guest speakers and their topics

| date | guest speaker | title of lecture |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| abstract Music has the ability to evoke powerful emotions in listeners and performers alike, and it has even been proposed that the expression and communication of emotion may be the most fundamental function of music. Although a fair amount of research has been carried out to investigate the psychological mechanisms underlying music-induced emotions, it is still somewhat of an enigma how an auditory stimulus without any explicit semantic meaning is able to move us to tears. This talk explores the fascinating phenomenon of music-induced emotions, and introduces theories that offer an account of the underlying psychological mechanisms. The second part of the talk will focus on the fascinating and paradoxical case of sad music. Can sad music evoke real sadness listeners? Why should listening to music make one sad? How can sadness be enjoyable in an aesthetic context? And why do only some people enjoy listening to sad music? These questions will be discussed in the light of prevalent theories and recent empirical evidence. |

||

|

|

|

|

| abstract While the meanings of music may be unique to a particular society, there is good reason to believe that the cognitive abilities involved in music are shared cross-culturally, even universally. Indeed, such capacities are not necessarily restricted to music, but may also play their part in other domains of human behaviour and experience. Analysis of music thus takes us to the heart of human cognitive experience, and links music with other realms of cultural meaning such as social relationships or religious devotion. Taking examples from Indian classical music and sacred singing in Nepal, I’ll argue that processes of implicit learning enable musical structure to be learned; that recursive structure in music exploits the universal capacity for recursive thought, but may acquire culture-specific meanings; and that the structure of performance may articulate locally-defined cultural models, and at the same time generate the cross-culturally attested psychological state of “flow” |

||

|

|

|

|

| abstract When we engage with music, we do so in culturally-appropriate ways. In recent Western cultures, listening—consumption—has become privileged as the culturally-appropriate mode of engagement; and emotion or aesthetic experience as the proper forms of our response to music. These conceptions have been the foci of most scientific research into our engagement with music. Music is thus conceived of and investigated as a medium for presentation or display, reflecting or embodying abstract structures that we experience affectively or aesthetically. But in many world cultures—including our own—music is an interactive, participatory medium that has many different social roles and cultural embeddings, and participation in music may have consequences that are not limited to the affective or aesthetic domains. I shall suggest that by conceiving of music as a primary human mode of interaction, and by situating this idea within recent research on the human capacity for complex interaction, we can develop novel and effective approaches to exploring and understanding music and its functions in human life |

||

|

|

|

|

| abstract The analysis of music in audiovisual contexts provides a valuable framework in which to explore the links between musical structure and emotional response. Neuroscientific research on human emotion has predominantly used images as experimental stimuli. However, in recent years neuroscientists have found music to be a potentially helpful tool. This presentation will centre on the main outcomes of my doctoral research at Cambridge University, which investigated the effects of musical dissonance upon the emotional interpretation of visual information from cognitive and neuroscientific perspectives. Overall, this work demonstrated that the systematic manipulation of musical dissonance in controlled audiovisual paradigms could serve as a effective tool to identify and further investigate specific neurofunctional networks implicated in the appraisal of emotion and in theory of mind processing |

||

|

|

|

|

| abstract I shall argue that "music" is most productively construed as a communicative medium that is cognate with, and complementary to, language in the form of speech; the behaviours, sounds and concepts that we can characterise as music and as speech reflect aspects of the human communicative toolkit that are optimised for somewhat different ends. While we can think of speech as a deployment of communicative resources that can be used to change the information about states of affairs in the world shared between members of a culture, from an interactionist perspective music constitutes a deployment of similar communicative resources that can elicit the sense that each participant has the same awareness of the world and of each other. This approach can help to clarify relationships between music and language, in the form of speech; it can begin to resolve some of the implications of recent research that has shown aspects of music to have powerful effects on memory and social attitude; and its implication that music as a mode of interaction may possess humanly-generic properties provides us with new perspectives on the investigation of music beyond the bounds of western culture |

||

|

|

|

slides |

| abstract Die merkwürdigen und teils abgründigen Klangeffekte, die Ludwig van Beethoven im zweiten Satz seiner Klaviersonate op. 101 (dort im Mittelteil) komponiert, stellen eine Herausforderung für strukturelle Analysen dar. Der Vortrag möchte den Möglichkeiten einer Klärung nachgehen |

||

|

|

|

|

|

abstract This presentation argues that empirically driven research which has exhausted the strictly functionalist paradigm (input/functional localization of cortical activation) desperately seeks input that allows it to approach more volatile constructs such as autobiographical memory and musical empathy. A project by the London based art collective artEmergent which is called "Thought Conductor" will serve as backdrop for this critical assessment. Bibliographical references:

|

||

|

|

|

|

| abstract Professionelles Musizieren erfordert ein Höchstmaß an räumlich-zeitlicher feinmotorischer Präzision und bewegt sich hier an der Grenze des menschlichen Leistungsvermögens. Für die Musikphysiologie – wie auch für die Instrumentalpädagogik – ist die Identifizierung optimaler Bedingungen für den Erwerb und die Aufrechterhaltung feinmotorischer Präzision ein wichtiges Anliegen. Feinmotorische Fertigkeiten der Musiker lassen sich valide und reliabel objektivieren, wie beispielsweise für Pianisten und einem hier eingesetzten MIDI-basierten Verfahren gezeigt wurde. Durch gleichzeitige Betrachtung der musikalischen Performanz und biografischer Faktoren (z.B. Angaben zur Übehistorie und zu motivationalen Aspekten) lassen sich Einflussgrößen identifizieren, die den Erwerb und die Aufrechterhaltung feinmotorischer Präzision am Instrument begünstigen. Als hirnphysiologische Korrelate wurden funktionelle und strukturelle Anpassungsvorgänge des Musikergehirns identifiziert, die mit der musikalischen Entwicklung einhergehen und deren Ausprägungen z.T. mit den feinmotorischen Fertigkeiten oder mit Expertise-assoziierten biografischen Faktoren korrelieren. In der Musikermedizin ist die so genannte Musikerdystonie eine zentrale Herausforderung. Sie gehört zu den tätigkeitsspezifischen fokalen Dystonien und ist charakterisiert durch den Verlust der feinmotorischen Kontrolle der Bewegungen am Instrument. Die Krankheitsmechanismen der Musikerdystonie sind nicht eindeutig geklärt. Familiäre Häufungen legen einen hereditären Zusammenhang nahe, infolgedessen steht die Musikerdystonie derzeit im Fokus neurogenetischer Untersuchungen. Die Therapie zielt darauf ab, die stark fixierten dystonen Bewegungsmuster zu lockern und durch nicht-dystone Bewegungen zu ersetzen. Die Objektivierung musikalischer Performanz konnte im vergangenen Jahrzehnt dazu beitragen, sowohl die Diagnostik als auch das Therapiemonitoring zu verbessern. Unter Einsatz der vorhandenen Therapieoptionen lässt sich heute bei der Hälfte der Musiker mit Handdystonien eine deutliche Verbesserung der Bewegungskontrolle am Instrument erzielen. Für die Zukunft sind (a) eine Optimierung der Therapien und (b) eine Identifizierung eines protektiven Verhaltens am Instrument im Hinblick auf eine effektive Prävention wünschenswert |

||

|

|

|

-> slides |

| abstract Theories of musical form have long been criticized for their tendency to reduce the essence of multidimensional works of art to simplistic, a-historical schemata. Such criticism is undermined, however, by the current revival of Formenlehre in North-American music theory. Although this “New Formenlehre” has led to a remarkable refinement of the analytical apparatus, the question of what it means to perceive musical form in real-time (and not just identify it in the written score) has been largely ignored. My talk therefore aims to shed light on the scant empirical evidence regarding the dimensions and limitations of the perceptibility of musical form. In so doing, I shall also explain the basic principles of both the experimental methodologies used and the analysis of musical form. The main argument I shall develop in my talk is that the cognition of supposedly abstract formal relationships is inextricably tied up with internalized, implicit stylistic knowledge about historically contingent voice-leading models (or topoi) and the formal functions they serve to express |

||

|

|

|

-> slides |

| abstract Musikkognition und Musiktheorie unterscheiden sich hinsichtlich ihrer epistemologischen Voraussetzungen, Erkenntnisziele und Methoden. Sie miteinander zu verknüpfen wirft eine Reihe von Fragen auf. Welche Konstellationen, funktionalen Rollen, Hierarchisierungen der Disziplinen sind im Begriff der kognitiven Musiktheorie mitgemeint? Wie konzeptualisieren sich die Disziplinen gegenseitig? Welche Kognitionsbegriffe sind an bisherigen kognitionswissenschaftlichen Reformulierungen von Musiktheorie beteiligt – und welche nicht? Im Dialog mit drei paradigmatischen Texten und anhand einer multiperspektivischen Analyse eines Ausschnitts der Arietta aus Beethovens op. 111 soll deutlich werden, dass Kooperationen von Musikkognition und Musiktheorie dort am ehesten zu überzeugen vermögen, wo nicht versucht wird, die Differenz ihrer Herangehensweisen zu nivellieren. |

||

|

|

|

|

| abstract The recent ascent of data-driven approaches in academic and commercial contexts on the one hand, and the relative maturity of music information retrieval and audio analysis on the other, provide a fruitful setting for developing a big data approach to music analysis. I will explore different implications of this approach, while touching upon specific challenges, limitations, and opportunities it can offer. My starting point will be a discussion of a recent project titled 'Digital Music Lab – Analysing Big Music Data' which involved several London universities and the British Library (completed in March 2015). I will discuss the project's achievements while describing several test-cases including examples from Ethnomusicology and popular music. I will then concentrate on a particular example from the field of early music performance practice, which involves the application of the big data approach to the analysis of tuning and temperament in harpsichord recordings |

||

|

|

|

|

| abstract Both music and language organize sound to create meaning and both are universal and particular for the species: All and only humans have them. What is the difference, then? In my talk I will elaborate the claim that language and music share many, but not all levels of meaning: illocutionary, emotional and conversational meanings can be observed in both music and language, but propositional semantics based on truth conditions and driven by logical operators is a notion that makes sense to describe linguistic, but not musical utterances. To express propositional semantics, language makes use of double articulation, a twofold structure that is absent in music: the linguistic sound system organizes not only itself in prosodic categories like syllables, feet and phrases, but also codes an abstract morphological system which contains lexical and grammatical meaning in order to create propositions. This second system exploits phonetic events of all kinds, from single articulatory features to the positions of accents, in order to establish contrasts between words and sentences. The same phonetic events are organized in music without the need to construct propositions: They can be organized obeying metrical, rhythmic and harmonic principles strictly, while these principles only have a secondary force in linguistic utterances. The shared levels of meaning coincide very often also in ways of expression: pitch, speed and loudness. Thus, music and language are different by the ranking of constraints on common principles. These observations may help to defend a connectionist view on the cognitive architecture of the two domains. |

||

Die Finanzierung des Zukunftskonzeptes der TU Dresden erfolgt aus Mitteln der Exzellenzinitiative des Bundes und der Länder.