Moon wood

Table of contents

- From "moon diet" to "moon wood" - anything goes?

- What is "moon wood"?

- The right time

- Alleged evidence

- Practically relevant differences in wood properties necessary

- Investigations of wood properties are usually not easy to carry out

- Advertising arouses desires

- Scientific knowledge vs. mythifying culture of remembrance

- Future handling of the "moon wood" issue

- More on the subject of "moon wood":

An overview of publications by the Chair of Forest Utilization on its own research results on the subject of "Moon and Wood" and "Moon and Christmas Trees" can be found under the heading "Publications".

From "moon diet" to "moon wood" - anything goes?

Careless handling of "moon wood" damages the image of wood in general.

Individual forest owners, sawmills and wood processing companies have specialized in harvesting and processing "moon wood", which is said to have particularly good wood properties. It is not uncommon for buyers to pay a significantly higher price for "moon wood" compared to wood from conventional felling. However, careless handling of "moon wood" can lead to damage to the image of wood in general and to legal consequences.

What is "moon wood"?

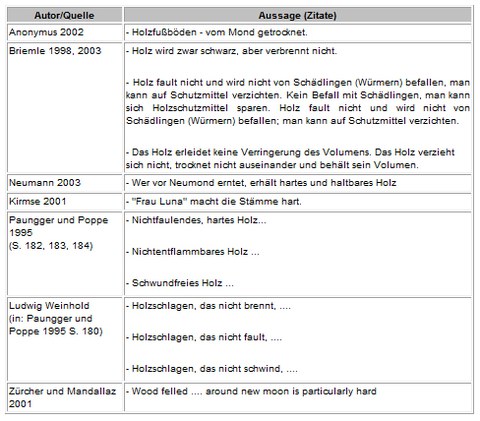

Moon wood" or "moon phase wood" is wood that is harvested at a certain moon phase that is considered "favorable" and is therefore said to have a number of exceptional wood properties (see Table 1). The effects on wood properties that can supposedly be achieved by observing the right time for felling are extremely diverse. All regulations that deal with felling time rules speak a clear and unambiguous language when quality statements are made for "moon wood": It does not burn, it does not rot/worm, it does not work! In addition to these three basic statements, one occasionally finds further alleged hallmarks of quality for "moon wood", e.g. the statements that "moon wood" is particularly dry and hard.

The right time

An extensive analysis of Central European forestry regulations and other forestry literature has shown that the felling of wood according to the phases of the moon is very well anchored in historical forestry literature, but that the diversity of the regulations alone means that it is not possible to speak of a generally valid rule. There are often even contradictory statements and regulations that indicate arbitrariness or, on closer inspection, can be explained by local conditions such as climate, geographical location, sovereign interests and much more (cf. TRIEBEL and BUES 2000). For various rules, it has been proven that the practice of transcribing sets of rules, which has been common for centuries, has led to errors in the transmission and thus a distortion of the meaning of certain traditional rules (FELLNER and TEISCHINGER 2001). Today, the waning moon is generally said to have a positive influence on the properties of wood. This also applies to most nature and farming rules from German-speaking countries (FELLNER and TEISCHINGER 2001).

In addition to the waning moon as the "right time" for timber harvesting, wood harvested on certain days is said to have special properties. A particularly frequently cited example of this is March 1. According to "ancient sources", wood felled on this day is not supposed to burn. This rule, which is rigid in terms of the date and significant for the quality of the wood, is documented very early in forestry literature. It can be found in the literature of JOHANNES COLERUS (1680) as well as in Ober (1912; in PAUNGGER and POPPE 1995).

These and other felling dates relating to specific days and periods may not have taken into account the changeover from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar in 1582. At the instigation of Pope Gregory XIII, the clock was set forward by a whole 10 days in the night from October 4 to 5 in 1582, i.e. to October 15 (PULS 2000). While the reform of the calendar was carried out quickly in the Catholic areas of Europe, the last Protestant countries only agreed to jump from February 18 to March 1 of the following year in 1699, thus introducing a uniform date throughout Germany in 1700 - 118 years late. No one knows which rules came into being before or after the Gregorian calendar reform, and which were adapted or not adapted.

Alleged evidence

Many ancient wooden buildings prove that wood is a durable building material. The stave churches in Scandinavia, the rustic wooden houses of mountain farmers in the Alps or the ornately decorated pagodas and palaces in Japan and China provide impressive examples of this.

These examples of wooden architecture are often associated with "moon wood". As expected, it is usually not possible to provide evidence that certain felling dates, moon phases or similar were adhered to when the timber was harvested, as in some cases many centuries have passed since the buildings were erected. When looking at the impressive evidence of traditional timber construction, the trained eye will recognize that the respective master builders mastered the various rules of constructive (structural) timber protection. A large number of impressive examples can be found in CLAUSNITZER (1989). Even after centuries, wood that has been protected from the weather shows no significant changes in its properties. If constructive measures were not sufficient to protect the wood permanently, chemical wood preservatives were used. In contrast to the supposedly natural and ecological construction methods of our ancestors, it has been proven that these builders were not cautious in their use of chemicals. CLAUSNITZER (1989) impressively documents the use of lead, arsenic and mercury, among other things, during every documented epoch.

Practically relevant differences in wood properties necessary

For a better understanding of the properties of wood, the following principles must be taken into account:

- The natural range of variation in wood properties is wide.

- The natural range of variation has not yet been sufficiently investigated for many wood properties.

- As the natural range of variation in wood properties is large, it is important to look for significant rather than minor differences.

In wood research, it has become customary to speak of practical wood property differences only when the differences lie outside the natural variation range of wood properties. For the most important wood properties, practical differences exist if the mean values of the tested properties deviate by at least 10 % from those of a comparison sample.

In the search for the traditional influences of the moon on wood properties, it must also be noted that people in earlier times did not have electron scanning microscopes, precision scales and universal testing machines to examine wood felled in the "right light". They were also unfamiliar with computers and statistical programs, which today are used to calculate the mean values of wood properties of different collectives to several decimal places and mathematically and statistically test for significant differences. So if differences in the properties between "moon wood" and wood from normal felling have been handed down, then they must be clear differences, striking changes in the properties of the wood that are obvious to everyone and therefore relevant in practice.

For the practical use of wood, this means A customer who pays 20% more for "moon wood" compared to wood from conventional felling, for example, is entitled to receive 20% better wood properties compared to the best wood quality of trees from the cheaper normal felling. Possible "homeopathic" differences in wood properties between normal wood and "moon wood" in no way justify such price differences (even if they are mathematically and statistically significant, because everyone knows that even the smallest differences in mean values can be made significant by increasing the sample size).

Investigations of wood properties are usually not easy to carry out

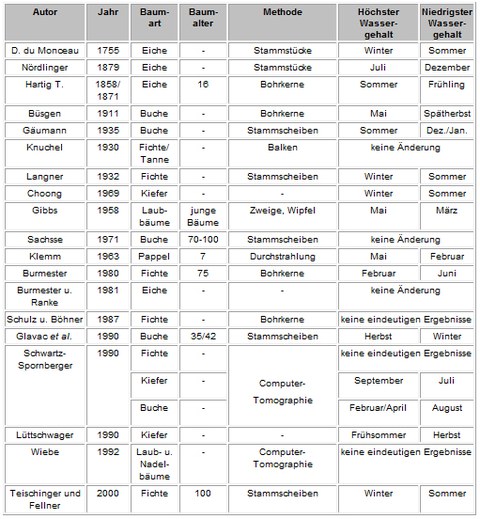

A question that can be answered quickly by practitioners: When does the tree have the highest wood moisture content, in summer or in winter? Everyone has their own opinion on this, based on their own experience. Check for yourself and then take a look at Table 2: Would you have thought so? Depending on the type of tree, the age of the tree and the method of examination, completely contradictory statements can be made about the moisture content in the sapwood. This relatively simple example is intended to show that only a large number of investigations using suitable and standardized methods allow generally valid wood science statements to be made. Individual findings should therefore always be viewed with the necessary skepticism.

Advertising arouses desires

Advertising with the alleged advantages of "moon wood" arouses wishes and justified expectations. Imagine this: A builder is interested in "moon wood" and studies the information on the correct felling time, e.g. in the agricultural moon calendar for 2003, compiled by BRIEMLE according to PAUNGGER and POPPE(www.astro-forschung.de):

For "boards and timber" as well as for "particularly hard wood", felling at waxing moon is recommended, whereas for "furniture and tool wood", "non-rotting wood", "non-shrinking wood" as well as "bridge and boat wood", felling at waning moon phase is recommended. Aren't bridges made from planks and other construction timber? Doesn't tool wood have to be particularly hard? Isn't it an advantage if boards and timber don't rot and shrink? How should the moon-believing wood lover who wants a non-rotting roof truss made of timber, for example, decide?

Bild 2: Reklamiertes „Mondphasenholz“ für einen Dachstuhl: Rundholzeinschlag Anfang Februar 2000, 225 fm Fichte und Kiefer. Rundholzeinschnitt in einem Sägewerk der Region während der Sommer- und Herbstmonate. Gesamtschaden durch Pilz- und Insektenbefall am Rund- und Schnittholz ca. 15.000,-- Euro

Or the following case: A builder reads about the alleged advantages of "moon wood" and is understandably enthusiastic. The house for the family must be built from such wood, wood that does not burn, does not rot, does not work, is particularly dry and hard. A forestry office is quickly found, as the "moon wood" range is readily available on request - for an extra charge, of course. The timber is felled on schedule "in the right appearance". The logs are ready in the forest for removal to the sawmill. But it is not brought from the forest to the sawmill quickly. "No hurry, it's "moon wood", nothing can happen to it," the builder replies to the worried forester. When the logs finally reach the sawmill, the disillusionment is great: the "moon wood" shows the typical storage damage (see picture 2). The client becomes thoughtful. If "moon wood" already causes such problems, what is it like with wood from conventional felling? Wood seems to be a problematic building material after all. And so the client very probably decides to build his house in brick to be on the safe side!

Scientific knowledge vs. mythifying culture of remembrance

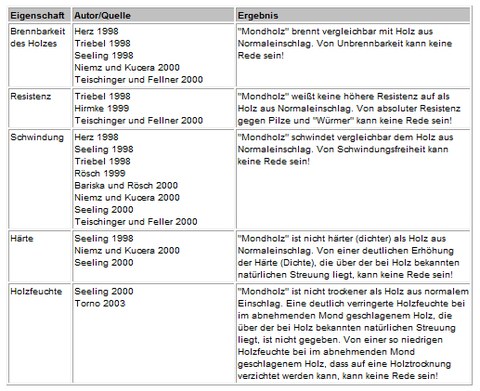

Knowing that for over 250 years attempts have been made again and again to research lunar analogies and effects on wood, the ignorance shown towards the findings is astonishing. Wood burns and works at all times. And yet skepticism towards scientifically conducted and repeatable experiments prevails (see Table 3). Knowledge from the so-called "good old days", combined with elements of meaningful symbolism as told by the grandfather, from the Alpine region, traditional craftsmanship, etc., on the other hand, is met with untested basic trust, like a religious process.

Tabelle 3: Ergebnisse von Untersuchungen angeblicher Eigenschaften von "Mond(phasen)holz" (Auswahl von aktuellen Untersuchungen als vorläufigs Ende einer langen Reihe von wissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen zum Thema "Mondholz", die vor etwa 250 begannen und immer zu vergleichbaren Ergebnissen kamen).

In the postmodern age, evidence-seeking, enlightening science is joined by a belief in holistic observation, in which everything that is inexplicable, supernatural or tainted with mythical elements is absorbed.

The general belief in lunar influences and the special benefits of "moon wood" is promoted in a special way by the prevailing trends of the time. The linking of various myth-laden objects of German culture is extremely helpful in this context. Favorite themes of German fairy tales - water, the moon and the forest - combined with a return to traditional and regional knowledge from supposedly better times, which can be seen as a response to mass production and the loss of identity in modern society, provide the material which, promoted by a justifiably strengthened ecological awareness, ultimately opens up new markets.

Bild 3: Mondholz mit Schäden durch falsche und zu lange Lagerung. Der Kunde verließ sich darauf, daß „Mondholz“ - wie oft behauptet - nicht fault und nicht wurmt

The ignorance with which the multiple proofs of a lack of correlation between felling time and timber quality are countered must be met with recognition of the product of history. After all, myths and stories do not need to claim to be true. Cultural identity - and "moon phase wood" obviously creates this - is becoming a self-runner in modern marketing. "Moon wood" has fortunately revived interest in wood. The fact that wood as a product, whose charms as a building material come to the fore quite inconspicuously and incidentally, plays a subordinate role, and that the decision to buy and demand is instead primarily due to the story behind the product, should definitely be mentioned.

However, the sudden fall of a steep career is inevitable if suppliers of "moon wood" confuse product and story. The number of disappointed "moon wood" buyers is growing, and the severity of the possible consequences for the entire product range cannot be foreseen.

Future handling of the "moon wood" issue

The explanations above reveal the problems associated with the special "moon wood" range. Discussions on the subject of "moon wood" are controversial and often emotional. Profiteering with as yet unproven properties of "moon wood" carries the risk of bringing the raw material wood into disrepute in general. It therefore seems necessary to establish certain guidelines when dealing with the subject of "moon wood":

| a. | Research into "moon wood" must be continued. |

| b. | Research on "moon wood" must not be dismissed as "esoteric" from the outset. |

| c. | Research results obtained on "moon wood" must be reproducible. |

| d. | Possible differences in the wood properties of "moon wood" and wood from conventional felling must lie outside the natural range of variation of the wood properties investigated in order to be of practical relevance. |

| e. | A mathematical-statistical validation of differences in the properties of "moon wood" and wood from conventional logging is the basis for scientific statements, but this does not automatically mean that it is relevant in practice. However, in order to establish "moon wood" as a special assortment on the market at higher prices, the advantages of "moon wood" must be relevant in practice. |

| f. | When reproducible and practice-relevant differences in properties between "moon wood" and normal wood have been proven at any time, it is time to make the results known to the general public. |

| g. | Only on the basis of reproducible and practice-relevant differences between "moon wood" and normal wood is advertising with the special properties of "moon wood" serious and a higher sales price justified. |

| h. | False promises or a lack of information about the properties of "moon wood" can have legal consequences. |

More on the subject of "moon wood":

Anonymus 2002: Holzfußböden – vom Mond getrocknet. Beilage zum Holz-Zentralblatt 128: B+H Nr. 1/Januar 2002: 11

Bariska, M.; Rösch, P. 2000: Fällzeit und Schwindverhalten von Fichtenholz. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 151: 439 - 443

Briemle, G. 1998: Vom rechten Zeitpunkt. Der forstliche Mondkalender für 1999. Wald und Holz 16: 31 - 33

Briemle, G. 2003: Der landbauliche Mondkalender für 2003 – Land- und forstwirtschaftliche Arbeiten zum richtigen Zeitpunkt.

Bues, C.T.; Triebel, J.; Schönwolf, M. 2003: Mondholz – ein Fall für den Staatsanwalt? Holz-Zentralblatt 129: 1290 - 1291 und 1346/1350

Clausnitzer, K.-D. 1989: Historischer Holzschutz im Hochbau. Dissertation, Fachbereich Architektur der Universität Hannover. 220 Seiten.

Colerus J. 1680: Oeconomia Ruralis et Domestica. In Verlegung Johann Baptistä Schönwetter Sel. Erben, Frankfurt am Mayn, 732 Seiten Fellner, J.;

Teischinger, A. 2001: Alte Holzregeln. Österreichischer Kunst- und Kulturverlag, Wien: 160 Seiten

Herz, A. 1998: Einfluß des Fällzeitpunktes auf das Schwindverhalten und die Feuchte des Holzes von Fichte, Literaturübersicht und Pilotstudie. Institut für Forstbenutzung und Forstliche Arbeitswissenschaft, Universität Freiburg

Hirmke, M. 1999: Einfluß des Schlägerungszeitpunktes auf die natürliche Dauerhaftigkeit von Fichte (Picea abies [L.] Karst.). Diplomarbeit, Universität für Bodenkultur, Wien

Kirmse, R. 2001: "Frau Luna" macht die Stämme hart. Niedersächsische Landesforsten, Waldinformation 1/2001: 16

Neumann, N. 2003: Wer vor Neumond erntet, erhält hartes und haltbares Holz. Niedersächsische Landesforsten, Waldinformation 2/2003: 20 - 21 Niemz, P.;

Kucera, L. J. 2000: Zum Einfluß des Fällzeitpunktes auf wesentliche Eigenschaften von Fichtenholz – Eine Überprüfung publizierter Thesen. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 151: 444 – 450

Paungger, J.; Poppe, T. 1995: Vom richtigen Zeitpunkt. Hugendubel, München

Puls, K. E. 2000: Kalendergeschichten. Die wechselvolle Geschichte unseres Kalenders über 5000 Jahre. Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau 53: 5 - 16

Rösch, P. 1999: Untersuchungen über den Einfluss des Fällzeitpunktes bezüglich Mondphasen auf das Trocknungs- und Schwindverhalten von Fichtenholz (Picea abies Karst.). Diplomarbeit der Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule Zürich, Abteilung Forstwissenschaften, Professur Holzwissenschaften, 58 Seiten

Seeling, U. 1998: Mondholz schwindet und brennt nicht? AFZ/Der Wald 53 (26): 1599 - 1601

Seeling, U. 2000: Ausgewählte Eigenschaften des Holzes der Fichte (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) in Abhängigkeit vom Zeitpunkt der Fällung. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 151: 451 – 458 Teischinger, J.;

Fellner, A. 2000: Alte Regeln neu interpretiert – Praxisversuche mit termingeschlägerem Holz. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 151: 425 – 431 Torno, S. 2003: Holzeinschlag in unterschiedlichen Mondphasen – Eine Überprüfung an ausgewählten Eigenschaften des Fichtenholzes (Picea abies Karst.). Diplomarbeit, Professur Forstnutzung, Fachrichtung Forstwissenschaften Tharandt, TU Dresden, 94 Seiten

Triebel, J. 1998: Mondphasenabhängiger Holzeinschlag – Literaturbetrachtung und Untersuchungen ausgewählter Eigenschaften des Holzes von Fichten. Diplomarbeit, Professur Forstnutzung, Fachrichtung Forstwissenschaften Tharandt, TU Dresden, 106 Seiten Triebel, J.;

Bues, C.T. 2000: Forstgeschichtliche Betrachtungen zur Bedeutung der mondphasenabhängigen Fällzeitregelung in Forstordnungen und anderem forstlichen Schrifttum. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Forstwesen 151: 432 – 438

Wiebe, S. 1992: Untersuchungen zur Wundentwicklung und Wundbehandlung an Bäumen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Holzfeuchte. naugural-Dissertation, Fakultät für Forstwissenschaften, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 131 Seiten und Bildband-Anhang. Zürcher, E.;

Mandallaz, D. 2001: Lunar synodic rhythm and wood properties: traditions and reality – experimental results on Norway spruce (Picea abies Karst.). L ábre 2000 = 2000 the tree: 4 th International Symposium on Tree held at the Montreal Botanik Garden, Aug. 20 – 25, 2000, Montreal; Tagungsband: 244 - 250

Hinweis: Die Technische Universität Dresden widmete die Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift Ausgabe 1/2 2005 dem Thema: Der Mond - Sein und Schein. Zahlreiche Beiträge - auch zum Thema "Mondholz" - der unterschiedlichsten Wissensdisziplinen sind in diesem Heft zusammengestellt.

Neuere Bücher mit Bezügen zu "Mondholz"

Brigitte Röthlein: Der Mond (2008), dtv-Verlag

Aussagen und Kommentare zum Thema "Mondholz" auf den Seiten 229 bis 236

Rudi Palla: Unter Bäumen (2006), Paul Zsolnay Verlag

Aussagen zum Thema "Mondholz" auf den Seiten 183 bis 184