16.06.2015

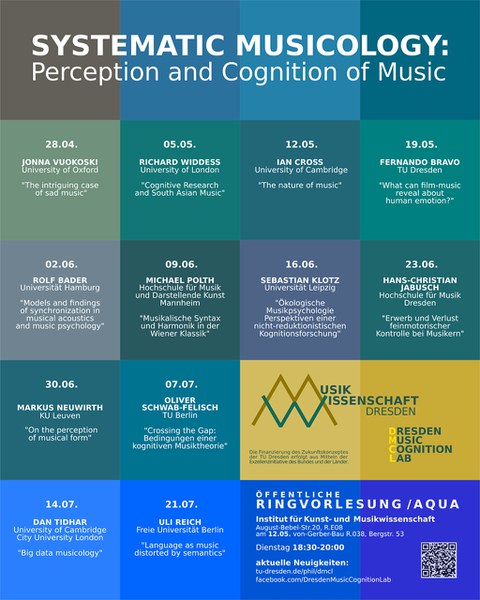

Ringvorlesung “Systematic Musicology: Perception and Cognition of Music”

Wieso gibt es Musik und was lehrt sie uns über das menschliche Denken?

Wieso genießen wir es, traurige Musik zu hören? Wie verhalten sich Musik und Sprache zueinander? Auf welche Weise funktioniert Filmmusik?

Die Ringvorlesung “Systematic Musicology: Perception and Cognition of Music”, organisiert vom 2015 gegründeten Dresden Music Cognition Lab (DMCL) der TU Dresden, beleuchtet diese und weitere Fragen.

In zwölf unabhängigen Vorträgen beschäftigen sich internationale Wissenschaftler mit den Phänomenen Musik und Musikwahrnehmung anhand aktueller Forschungsfragen aus diversen interdisziplinären Perspektiven von Musiktheorie, experimenteller Psychologie, kognitiven Neurowissenschaften, bishin zu Evolutionstheorie und Informatik.

Programm

28. April 2015

Jonna Vuoskoski, University of Oxford

The intriguing case of sad music

Music has the ability to evoke powerful emotions in listeners and performers alike, and it has even been proposed that the expression and communication of emotion may be the most fundamental function of music. Although a fair amount of research has been carried out to investigate the psychological mechanisms underlying music-induced emotions, it is still somewhat of an enigma how an auditory stimulus without any explicit semantic meaning is able to move us to tears. This talk explores the fascinating phenomenon of music-induced emotions, and introduces theories that offer an account of the underlying psychological mechanisms. The second part of the talk will focus on the fascinating and paradoxical case of sad music. Can sad music evoke real sadness listeners? Why should listening to music make one sad? How can sadness be enjoyable in an aesthetic context? And why do only some people enjoy listening to sad music? These questions will be discussed in the light of prevalent theories and recent empirical evidence.

05. Mai 2015

Richard Widdess, SOAS University of London

Cognitive Research and South Asian Music

While the meanings of music may be unique to a particular society, there is good reason to believe that the cognitive abilities involved in music are shared cross-culturally, even universally. Indeed, such capacities are not necessarily restricted to music, but may also play their part in other domains of human behaviour and experience. Analysis of music thus takes us to the heart of human cognitive experience, and links music with other realms of cultural meaning such as social relationships or religious devotion. Taking examples from Indian classical music and sacred singing in Nepal, I’ll argue that processes of implicit learning enable musical structure to be learned; that recursive structure in music exploits the universal capacity for recursive thought, but may acquire culture-specific meanings; and that the structure of performance may articulate locally-defined cultural models, and at the same time generate the cross-culturally attested psychological state of “flow”.

12. Mai 2015

Ian Cross, University of Cambridge

The nature of music

When we engage with music, we do so in culturally-appropriate ways. In recent Western cultures, listening—consumption—has become privileged as the culturally-appropriate mode of engagement; and emotion or aesthetic experience as the proper forms of our response to music. These conceptions have been the foci of most scientific research into our engagement with music. Music is thus conceived of and investigated as a medium for presentation or display, reflecting or embodying abstract structures that we experience affectively or aesthetically. But in many world cultures—including our own—music is an interactive, participatory medium that has many different social roles and cultural embeddings, and participation in music may have consequences that are not limited to the affective or aesthetic domains. I shall suggest that by conceiving of music as a primary human mode of interaction, and by situating this idea within recent research on the human capacity for complex interaction, we can develop novel and effective approaches to exploring and understanding music and its functions in human life.

19. Mai 2015

Fernando Bravo, TU Dresden

What can film-music reveal about human emotion?

The analysis of music in audiovisual contexts provides a valuable framework in which to explore the links between musical structure and emotional response. Neuroscientific research on human emotion has predominantly used images as experimental stimuli. However, in recent years neuroscientists have found music to be a potentially helpful tool. This presentation will centre on the main outcomes of my doctoral research at Cambridge University, which investigated the effects of musical dissonance upon the emotional interpretation of visual information from cognitive and neuroscientific perspectives. Overall, this work demonstrated that the systematic manipulation of musical dissonance in controlled audiovisual paradigms could serve as a effective tool to identify and further investigate specific neurofunctional networks implicated in the appraisal of emotion and in theory of mind processing.

02. Juni 2015

Rolf Bader, Universität Hamburg

Models and findings of synchronization in musical acoustics and music psychology

I shall argue that "music" is most productively construed as a communicative medium that is cognate with, and complementary to, language in the form of speech; the behaviours, sounds and concepts that we can characterise as music and as speech reflect aspects of the human communicative toolkit that are optimised for somewhat different ends. While we can think of speech as a deployment of communicative resources that can be used to change the information about states of affairs in the world shared between members of a culture, from an interactionist perspective music constitutes a deployment of similar communicative resources that can elicit the sense that each participant has the same awareness of the world and of each other. This approach can help to clarify relationships between music and language, in the form of speech; it can begin to resolve some of the implications of recent research that has shown aspects of music to have powerful effects on memory and social attitude; and its implication that music as a mode of interaction may possess humanly-generic properties provides us with new perspectives on the investigation of music beyond the bounds of western culture

09. Juni 2015

Michael Polth, University of Music and Performing Art Mannheim

Musikalische Syntax und Harmonik in der Wiener Klassik

16. Juni 2015

Sebastian Klotz, Universität Leipzig

'Thought Conductors' – Towards a non-reductionist music cognition research

Given the complexity of human auditory perception, models that rely on information theory concepts have been substituted by more ecologically nuanced perspectives on listening as a culturally situated practice. This presentation argues that empirically driven research which has exhausted the strictly functionalist paradigm (input/functional localization of cortical activation) desperately seeks input that allows it to approach more volatile constructs such as autobiographical memory and musical empathy. A project by the London based art collective art Emergent which is called "Thought Conductor" will serve as backdrop for this critical assessment.

23. Juni 2015

Hans-Christian Jabusch, Hochschule für Musik Dresden

Erwerb und Verlust feinmotorischer Kontrolle bei Musikern

Professionelles Musizieren erfordert ein Höchstmaß an räumlich-zeitlicher feinmotorischer Präzision und bewegt sich hier an der Grenze des menschlichen Leistungsvermögens.

Für die Musikphysiologie – wie auch für die Instrumentalpädagogik – ist die Identifizierung optimaler Bedingungen für den Erwerb und die Aufrechterhaltung feinmotorischer Präzision ein wichtiges Anliegen. Feinmotorische Fertigkeiten der Musiker lassen sich valide und reliabel objektivieren, wie beispielsweise für Pianisten und einem hier eingesetzten MIDI-basierten Verfahren gezeigt wurde. Durch gleichzeitige Betrachtung der musikalischen Performanz und biografischer Faktoren (z.B. Angaben zur Übehistorie und zu motivationalen Aspekten) lassen sich Einflussgrößen identifizieren, die den Erwerb und die Aufrechterhaltung feinmotorischer Präzision am Instrument begünstigen. Als hirnphysiologische Korrelate wurden funktionelle und strukturelle Anpassungsvorgänge des Musikergehirns identifiziert, die mit der musikalischen Entwicklung einhergehen und deren Ausprägungen z.T. mit den feinmotorischen Fertigkeiten oder mit Expertise-assoziierten biografischen Faktoren korrelieren.

In der Musikermedizin ist die so genannte Musikerdystonie eine zentrale Herausforderung. Sie gehört zu den tätigkeitsspezifischen fokalen Dystonien und ist charakterisiert durch den Verlust der feinmotorischen Kontrolle der Bewegungen am Instrument. Die Krankheitsmechanismen der Musikerdystonie sind nicht eindeutig geklärt. Familiäre Häufungen legen einen hereditären Zusammenhang nahe, infolgedessen steht die Musikerdystonie derzeit im Fokus neurogenetischer Untersuchungen. Die Therapie zielt darauf ab, die stark fixierten dystonen Bewegungsmuster zu lockern und durch nicht-dystone Bewegungen zu ersetzen. Die Objektivierung musikalischer Performanz konnte im vergangenen Jahrzehnt dazu beitragen, sowohl die Diagnostik als auch das Therapiemonitoring zu verbessern. Unter Einsatz der vorhandenen Therapieoptionen lässt sich heute bei der Hälfte der Musiker mit Handdystonien eine deutliche Verbesserung der Bewegungskontrolle am Instrument erzielen. Für die Zukunft sind (a) eine Optimierung der Therapien und (b) eine Identifizierung eines protektiven Verhaltens am Instrument im Hinblick auf eine effektive Prävention wünschenswert.

30. Juni 2015

Markus Neuwirth, KU Leuven

On the perception of musical form

Musikalische Formenlehre stand lange im Verdacht, die Essenz vielschichtiger Kunstwerke auf „musikferne Schemata“ bzw. „blutleere Konstruktionen“ zu reduzieren. Ein solcher Verdacht wird gegenwärtig durch ein Revival der Formenlehre in der anglophonen Musikwissenschaft eindrucksvoll widerlegt. Doch obgleich die sog. „New Formenlehre“ eine hochgradige Verfeinerung des Methodenapparats zur Folge hatte, wurde die dringliche Frage danach, was es heißt, musikalische Form(en) im realzeitlichen Verlauf wahrzunehmen (und nicht bloß lesend im Notentext zu identifizieren), kaum gestellt. Ziel des Vortrags (auf Englisch) ist es, die wenigen belastbaren empirischen Befunde zu Dimensionen und Grenzen der Wahrnehmbarkeit musikalischer Form kritisch zu beleuchten und dabei auch die Grundlagen sowohl der Experimentalmethodik als auch der musikalischen Formtheorie zu erläutern. Insbesondere soll die These diskutiert werden, dass der Nachvollzug selbst vermeintlich abstrakter Formzusammenhänge ohne internalisiertes Stilwissen bzgl. historisch differenzierter Tonsatzkonstellationen (Satzmodelle und Topoi) schlechterdings unmöglich ist.

Theories of musical form have long been criticized for their tendency to reduce the essence of multidimensional works of art to simplistic, a-historical schemata. Such criticism is undermined, however, by the current revival of Formenlehre in North-American music theory. Although this “New Formenlehre” has led to a remarkable refinement of the analytical apparatus, the question of what it means to perceive musical form in real-time (and not just identify it in the written score) has been largely ignored. My talk therefore aims to shed light on the scant empirical evidence regarding the dimensions and limitations of the perceptibility of musical form. In so doing, I shall also explain the basic principles of both the experimental methodologies used and the analysis of musical form. The main argument I shall develop in my talk is that the cognition of supposedly abstract formal relationships is inextricably tied up with internalized, implicit stylistic knowledge about historically contingent voice-leading models (or topoi) and the formal functions they serve to express.

07. Juli 2015

Oliver Schwab-Felisch, TU Berlin

Crossing the Gap: Bedingungen einer kognitiven Musiktheorie

14. Juli 2015

Dan Tidhar, University of Cambridge, City University London

Big data musicology

21. Juli 2015

Uli Reich, Freie Universität Berlin

Language as music distorted by semantics

Both music and language organize sound to create meaning and both are universal and particular for the species: All and only humans have them. What is the difference, then? In my talk I will elaborate the claim that language and music share many, but not all levels of meaning: illocutionary, emotional and conversational meanings can be observed in both music and language, but propositional semantics based on truth conditions and driven by logical operators is a notion that makes sense to describe linguistic, but not musical utterances. To express propositional semantics, language makes use of double articulation, a twofold structure that is absent in music: the linguistic sound system organizes not only itself in prosodic categories like syllables, feet and phrases, but also codes an abstract morphological system which contains lexical and grammatical meaning in order to create propositions. This second system exploits phonetic events of all kinds, from single articulatory features to the positions of accents, in order to establish contrasts between words and sentences. The same phonetic events are organized in music without the need to construct propositions: They can be organized obeying metrical, rhythmic and harmonic principles strictly, while these principles only have a secondary force in linguistic utterances. The shared levels of meaning coincide very often also in ways of expression: pitch, speed and loudness. Thus, music and language are different by the ranking of constraints on common principles. These observations may help to defend a connectionist view on the cognitive architecture of the two domains.