On the relationship between profession, professionalism, professionalization and professional understanding in political education

Despite various approaches to professional theory in related fields, there is a lack of theory development in the field of non-formal civic education (Hufer / Richter 2013: 17). In an analysis of various approaches to professional theory, Werner Helsper (2021: 121) also notes that "none of the approaches considers all areas and levels of what constitutes profession and professionalism equally comprehensively". Accordingly, he proposes combining different approaches into a multi-level model, which on the one hand distinguishes between different theoretical levels, but on the other hand also makes it possible to relate them to each other (ibid.: 133 f.). Helsper differentiates between a socio-theoretical macro level, which focuses on the "societal[...] significance of professions and professional action" (ibid.: 133) and "the integration of professions into structures of power and domination" (ibid.), and an organizational level, which considers "organizational integration and framing of professional action in organizations and institutionalized process patterns" (ibid.). In addition, he describes a micro level, which focuses on the concrete interactive actions of the professionals (cf. ibid.), and the subject level, which considers "the professionals as stakeholders in professional action" (ibid.), their knowledge, competencies and professional biographical developments (ibid.).

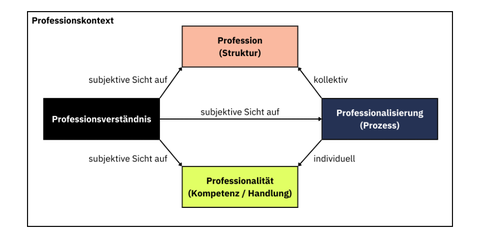

Based on these findings, the terms profession, professionalism, professionalization, professional context and understanding of profession can be distinguished from one another (see Figure 1). Even if these terms are clearly related in name, "[t]he decoupling of [these] concepts [...] is necessary, as the terms themselves pursue different orientations" (Liszt 2018: 52). These individual dimensions are described in the following overview:

Abbildung 1: Verhältnis Profession - Professionalität - Professionalisierung - Professionsverständnis (eigne Darstellung)

The term "profession" describes a "structural theoretical perspective" (Liszt 2018: 52), which classifies certain occupations as professions based on additional attributes. "In a first attempt at a definition, a profession could be understood as an academic occupation that is particularly recognized because it deals with a problem that is central to social reproduction and systematically applies the knowledge required for this" (Nittel 2000: 18). Based on this minimal definition, various professional sociological theories have now emerged (Breuer-Nyhsen 2018: 9). However, these tend to develop rather rigid, functionalist and indicator-based concepts of profession, which are not very suitable for the dynamic and heterogeneous field of extracurricular civic education (Schmidt-Lauff / Lehmann 2012: 29). It therefore seems more sensible in this area to "turn away from the goal of establishing a [...] profession along the lines of the classical professions" (Dinkelaker 2021: 195) and instead focus on the "specific requirements of professionalism in professional action" (ibid.).

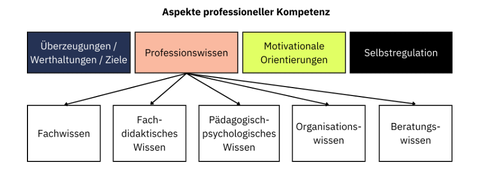

As an "action-theoretical perspective" (Liszt 2018: 52), "professionalism" in this context describes the personal prerequisites and skills that professionals "possess [and] which they are able to bring to bear interactively in concrete social professional situations" (Helsper 2021: 56). In order to map the various characteristic dimensions of professionalism as comprehensively as possible, the competency model designed by Kunter / Baumert (2011: 32) can be transferred to non-formal civic education (see Figure 2). This model identifies professional knowledge in various areas as the core of professional competence. In addition, the beliefs and motivational orientations of professionals and their ability to self-regulate also play a central role.

Abbildung 2: eigene Darstellung nach Baumert/Kunter (2011:32)

"Because professional action is not based on schematic F-patterns and causal recipes, but as a complex social, meaning-structured interactive event, it is susceptible to disruption, situational and case-specific and therefore fragile, it remains prone to failure and mistakes [...]. It is precisely then, however, that professionalism proves itself in the reflexive handling and (self-)critical collegial confrontation with these sources of error and potential for error" (Helsper 2021: 56).

At the same time, professionalism is defined by the fact that actions are perceived as professional by others (cf. Kaupke 2019: 10). Accordingly, although professionalism as a "quality of action" (Scheidig 2016: 307) is based on certain skills that can be acquired, it must always be re-established according to the situation (Liszt 2018: 67).

In contrast, "professionalization" describes a "processual perspective" (Liszt 2018: 52) with two dimensions: On the one hand, professionalization at the individual level encompasses the personal qualification process in which professional competence to act is developed and professionalism is thereby made possible (Helsper 2021: 56 f.). Ideally, the formation of knowledge and the development of a professional self-image (Liszt 2018: 77) should be the result of an interactive professionalization process, i.e. through the interaction and interlocking of academic and practical perspectives (Jütte / Walber 2012: 43 f.). On the other hand, professionalization can also take place on a collective level. While this has traditionally been associated with the development of a profession, collective professionalization is now understood more as an open-ended process (Dinkelaker 2021: 146 f.), which includes power-theoretical developments (e.g. expansion of influence, increase in income and social status) and quality-oriented professionalization (e.g. development of quality standards or professional ethics) (Liszt 2018: 72). Together, both dimensions can help to create and institutionalize the foundations for professionalism and the development of a profession (Helsper 2021: 56 f.).

The term "professional context" encompasses the "social, institutional and organizational framework conditions" (Helsper 2021: 56), which form a basis for action for all other dimensions, i.e. the environment in which a professional group exists, acts and develops. These include general social framework conditions (e.g. population structure or cultural infrastructure), situational conditions (e.g. socio-political or municipal policy measures), social and societal recognition or funding and support opportunities (Dinkelaker 2021: 16; Scheidig 2016: 309 f.; Zeuner 2013: 83).

The term "understanding of the profession" usually refers to the professional self-image or specifically "the subjective constructions of one's own [...] professional role and the ideas about [...] appropriate [professional] action" (Würfl / Schörner 2020: 187). Interpreted somewhat more broadly, this dimension encompasses the subjective view, i.e. ideas, perceptions and convictions, of political educators on the other three dimensions.

Literature for further reading:

- Breuer-Nyhsen, Julia (2018): Professionsverständnis in der Sozialen Arbeit als Lehrinhalt in der Hochschulausbildung. Eine Untersuchung an der Katholischen Hochschule NRW, Abteilung Aachen. Masterthesis im Studiengang Soziale Arbeit, Studienschwerpunkt Bildung und Teilhabe. Katholische Hochschule Nordrhein-Westfalen.

- Baumert, Jürgen / Kunter, Mareike (2011): Das Kompetenzmodell von COACTIV. In: Kunter, Mareike / Baumert, Jürgen et. al. (Hrsg.): Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften: Ergebnisse des Forschungsprogramms COACTIV (Waxmann), S. 29-53.

- Dinkelaker, Jörg (2021): Professionalität und Professionalisierung in der Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung. In: Dinkelaker, Jörg / Hugger, Kai-Uwe / Idel, Till-Sebastian / Schütz, Anna / Tünemann, Silvia (Hrsg.): Professionalität und Professionalisierung in pädagogischen Handlungsfeldern: Schule, Medienpädagogik, Erwachsenenbildung (Verlag Barbara Budrich). Opladen & Toronto, S. 141-203.

- Helsper, Werner (2021): Professionalität und Professionalisierung pädagogischen Handelns: Eine Einführung (Verlag Barbara Budrich). Opladen & Toronto.

- Hufer, Klaus-Peter / Richter, Dagmar (2013): Politische Bildung als Profession. Verständnisse und Forschung. In: Hufer, Klaus-Peter / Richter, Dagmar (Hrsg.): Politische Bildung als Profession. Verständnisse und Forschungen. Perspektiven politischer Bildung (Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung). Bonn, S. 13-19.

- Jütte, Wolfgang / Walber, Markus (2012): Interaktive Professionalisierungsszenarien in der Weiterbildung. In: Gruber, Elke / Wiesner, Gisela (Hrsg.): Erwachsenenpädagogische Kompetenzen stärken. Kompetenzbilanzierung für Weiterbildner/-innen (W. Bertelsmann Verlag). Bielefeld, S. 43-54.

- Kaupke, Christian (2019): Das Professionsverständnis in der öffentlichen Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. Individuelle Lösungen versus einheitliche Standards (Studylab). München.

- Liszt, Verena (2018): Professionalisierung in der Erwachsenenbildung. Qualitative Untersuchung von Absolventen und Absolventinnen der Wirtschaftspädagogik (Springer). Wiesbaden.

- Scheidig, Falk (2016): Pädagogisches Personal und Professionsentwicklung. In: Hufer, Klaus-Peter / Lange, Dirk (Hrsg.): Handbuch politische Erwachsenenbildung (Wochenschau Verlag). Schwalbach/Ts., S. 303-312.

- Schmidt-Lauff, Sabine / Lehmann, Annika (2012): Entwicklungsstränge im Professionalisierungsverständnis – eine reflexive Positionierung zu gegenwärtigen Kompetenzbilanzierungsverfahren. In: Gruber, Elke / Wiesner, Gisela (Hrsg.): Erwachsenenpädagogische Kompetenzen stärken. Kompetenzbilanzierung für Weiterbildner/-innen (W. Bertelsmann Verlag). Bielefeld, S. 23-41.

- Würfl, Christine / Schörner, Barbara (2020): Professionsverständnis von Schulsozialarbeit in der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. Eine quantitative Analyse für Österreich. In: Österreichisches Jahrbuch der Sozialen Arbeit, S. 181-202.

- Zeuner, Christine (2013): Erwachsenenbildung und Profession. In: Hufer, Klaus-Peter / Richter, Dagmar (Hrsg.): Politische Bildung als Profession. Verständnisse und Forschungen. Perspektiven politischer Bildung (Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung). Bonn, S. 81-96.