A small outbreak every day

(Interview from 2017)

Dagmar Möbius

Andreas Kurth learned how to work with communication technology before he started his degree at TU Dresden. Now, those skills are helping the doctor of biology to set up a high-containment laboratory. His research interest, however, is in dangerous pathogens. And bats.

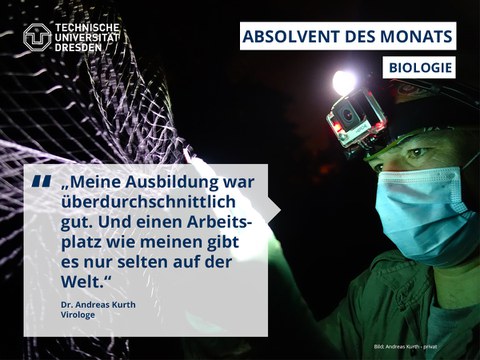

Andreas Kurth is the September 2020 Alumnus of the Month

"Life's better in flip flops" reads the sign on the wall of his office in Berlin's Robert Koch Institute (RKI). The sign was a gift from friends – a reference to his preferred footwear for work (of course, only when he has no official meetings). The 43-year-old has worked at the RKI since 2003. The RKI is the German federal government's central health body, and employs a staff of more than 1100. For the past four years, Kurth has managed the high-containment laboratory. He is aware that "workplaces like mine are few and far between." He cycles an hour to the site in Berlin's Wedding district almost every day.

Andreas Kurth had always been interested in biology and chemistry, and they came easily to him. He finished school in 1989, when the GDR collapsed. Initially, he wanted to become a carpenter or "do something technical." He ultimately opted for vocational training with a high school diploma (Berufsausbildung mit Abitur) in the field of communications engineering, and this took him from Dresden to the Deutsche Reichsbahn state railways in Berlin. During his subsequent military service as a paramedic, he became interested in how the body works, deciding to get his Diplom degree in biology from TU Dresden – a degree program launched in 1994. "Only medicine or only veterinary medicine was not broad enough for me," he explains. In his first year, eight professors and multiple assistants worked closely with him and around 35 fellow students. Kurth praises the course: "The education and training we received were very good." The skills he acquired in the complex representation of biological processes were particularly important to him. What was more, "anyone who was interested was given a contract as a research assistant," he recalls. From 1995 to 1997, he studied animal protozoa under the electron microscope with Professor Rolf Enzeroth at TU Dresden's Institute of Systematic Zoology. Parasites were an important focus for the travel-lover in his first year of study – although in this case, in an unintentional way. "On my first trip to Africa, I got infected with lungworms and took three months to recover."

Administrative tasks and science are both part of Dr. Andreas Kurth's work day

His scientific interest took the Dresden native back to Berlin after just a few semesters. Kurth began researching viruses with Dr. Hans Gelderblom at the Robert Koch Institute starting in 1997. He wrote his final-year dissertation on imaging. He remembers the act of graduation in 2000 as more or less a formality. "There was no celebration, you just picked up your certificate." Andreas Kurth filled the time until he began his doctorate with a few months' teaching at the "zoo school" at Dresden Zoo, and he greatly enjoyed the work with children. In spring 2001, he headed to Oregon State University in the US for nearly two years thanks to a DAAD doctoral scholarship for research abroad. He defended his doctoral thesis on epidemiological studies of the vesivirus at TU Dresden in the summer of 2004. Now, he smiles at the skepticism of some of his university lecturers about what would become of him.

Dr. Andreas Kurth has been working and conducting research at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin since 2003, including on various aspects of smallpox infections. He has been working on setting up the high-containment laboratory here for four years. In the future, Risk Group 4 pathogens will be diagnosed and researched in the only laboratory in Germany that meets the highest human medicine biosafety standard. The lab will work with highly pathogenic viruses such as Ebola, Lassa, and Nipah. Thirty to eighty percent of those infected with those viruses die after infection because there are still no treatment options. The four-story laboratory wing is scheduled for completion in the course of 2017. Trial operation will then take place with researchers wearing hazmat suits. They can work in the suits for up to five hours.

A view through the window: There is negative pressure in the high-containment laboratory. This prevents pathogens from escaping in the event of a leak. There are also a number of integrated safety and filter systems.

Andreas Kurth has not had a typical workday since he interrupted his academic career to head the BSL-4 lab. He has been in regular contact with planners and builders since the early stages of construction. "This lab is a prototype," he says. "No other company has built anything exactly like this before. A lot of things have to be agreed with us, the users." Although his vocational training is now useful in understanding the technical side, he was previously unaware that around 140 legal regulations, ranging from occupational safety and fire safety to genetic engineering, infection control, and animal welfare, had to be observed for a construction project like this one. Committee work is therefore also important. "I want to give my input so that overreactions to what are in some cases very old safety regulations don't make practical laboratory work even more difficult; so that we can still work." The virus expert is also part of a World Health Organization inspection team that regularly checks the work of two laboratories in Russia and the United States that research smallpox.

It started out as a one-man operation, but he has now put together a twelve-person group with experts from four different countries, including four scientists, a biosafety officer, four technical employees, and two animal keepers. "Finding personnel for tasks like this is not easy," Kurth explains. Only "people who are genuinely willing and able" are considered. In the future, visiting researchers will also be able to conduct their work in his team. Before things are up and running, there are initial scientific decisions to be taken. Kurth likes the variety of his current role, including the administrative work, but he is already thinking about the specifics of future practical research. Transmission mechanisms from animals to humans are a long-term area of interest for him. He is also driven by a desire to make fundamental progress on treatment for the Ebola virus, the existence of which we have known about for more than 40 years.

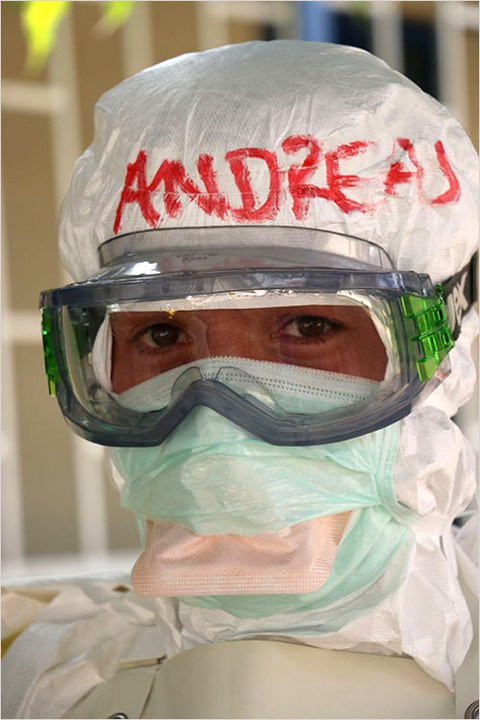

Working during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone in 2015

At the start of the Ebola epidemic in 2014, and again a year later, he spent several weeks in Guinea and Sierra Leone. During the yellow fever outbreak in mid-2016, he and colleagues set up and ran a laboratory in Congo – with operations coordinated by the European Mobile Laboratory project. "Such commitments are voluntary in the civilian sector; for me, they go without saying," Kurth says. In West Africa, he started work on setting up a bat center two years ago. There are plans to examine the animals in Germany at a later point. "There is evidence from field research that certain species of insectivorous bats may transmit Ebola. We want to find out where the viruses circulate, exploit clues, and recreate processes experimentally in the laboratory," he explains, looking ahead. He already knows that "proof will be hard to come by." He is looking for "the beginning of the story" and is aware that "each answer poses 100 new questions." He does not expect the first results until at least two years' time.

Comparisons with the 1995 US film "Outbreak" with Dustin Hoffmann come to mind. Events in the film revolve around a new type of virus that has first appeared in Africa, evoking associations with Ebola. What does the scientist think about it? He laughs and says, "It’s okay by the standards of the time and Hollywood." Because pathogens were developed as biological weapons, the army was involved (in the film). The military has the necessary logistical resources and can dispatch soldiers to dangerous areas. "But the little monkey wouldn't have been jumping around like that. Ebola kills monkeys," Kurth clarifies. Nonetheless, "there was also an Ebola virus in Africa that was harmless to humans, and was brought to the US via shipments of monkeys from the Philippines."

At the RKI, Dr. Andreas Kurth has also researched bioterrorism pathogens. Infamous "powder in the mail" is investigated in the lab to "rule out the possibility" of pathogens. Each time, multiple teams are involved. Fortunately, a dangerous pathogen has never been detected in the suspicious substances.

Most people in Dresden will have heard of the lesser horseshoe bat, which caused a stir during construction of the Waldschlösschen Bridge and led to delays for conservation reasons. Andreas Kurth has researched the little bat – or more precisely, samples from it. And? "You can find out quite a lot" about specific biological questions, he tells us.

2020 update

Reading the first article from two and a half years ago gives me a surprisingly good feeling when I look at the plans detailed. Anyone who has ever been involved in laboratory approval processes, arguments with regulatory agencies, and the management of complex scientific issues will understand that planning work feels much like weather forecasting. It is therefore great, and a little surprising, that our high-containment laboratory has been fully operational – i.e. we have been working with Ebola and other serious viruses – since 2018. Progress is also being made in science and research terms. We were able to establish an Ebola virus infection in the high-containment laboratory in the first imported bats from West Africa, and can now spend the next 10+ years addressing the resulting 100 new questions.

Contact:

Dr. Andreas Kurth

Robert Koch-Institut Berlin

Fachgebietsleiter - Hochsicherheitslabor - Zentrum für Biologische Gefahren und Spezielle Pathogene

Websites: