"You can make things happen that just aren't possible in the same way in Germany"

(Interview from 2019)

Susann Mayer / Dirk Lebe

Setting up banks in Africa? Working with cocoa farmers in Asia on saving money? Teaching at a university in Siberia? Talking about business with indigenous Mayan women's groups in Latin America? How do you get a job like that? Well, mostly through happy coincidence – at least that's what the economist Dirk Lebe thinks.

Dirk Lebe is the May 2020 Alumnus of the Month

While studying business management at TUD, he spent a semester in Salvador de Bahia, a city in Brazil with rich African influence. When he graduated in 2004, he headed to Ghana. In thinking back on his time there, he still vividly remembers the “markets full of people adorned in colorful robes. Gorgeous!”

Many people will be familiar with the concept of microfinance, which reduces banking to the bare essentials. It centers mainly on small loans for self-employed "entrepreneurs" and savings products for customers who are not a very attractive target group for most banks. "After decades of hype surrounding microcredit, however, you need to look at it with a critical eye. Many banks are not Good Samaritans," says Lebe. Many of the customers are not really entrepreneurs either. They are single-person businesses, because jobs are scarce and social security is non-existent. The only way to survive is to try to make ends meet with a business. However, the money is often not there and the only solution many people turn to is a loan.

Dirk Lebe helped establish a microfinance bank in Angola. "It's hard to imagine sitting across from a 45-year-old who, when you set up his account, tells you with shining eyes that he has just opened the very first account he's ever had." Other things just made him shake his head. For example, when the cash-in-transit company forgets to bring an empty case for the money. And so he was forced to pack a very large sum of money into his colleague's handbag, take his seat in an armored truck with eight security guards, all well over 6 feet tall and holding Kalashnikovs, and drive back from the central bank to the branch with the emergency lights flashing, past Luanda's permanent traffic jam. Levels of education in Africa in particular can be very low, and this is a big challenge and often quite frustrating. Schools cost money – money that not everyone has.

Obligations: planting a cocoa tree in Sulawesi, Indonesia

Dirk Lebe's first visit to Indonesia was to Aceh in the north of Sumatra. Reconstruction after the 2004 tsunami brought out both the good and bad sides of development cooperation, in particular what happens when too much money is pumped into a region and there is a global zeal to spend it. "Banks were also affected and had to get up and running." After a stopover in Germany, where Lebe completed his doctorate "with the competition in Frankfurt," he moved on to Mozambique, again to set up a bank. The next step was a semester at a university in Siberia. "There, of course, it was on the chilly side in winter," he says, laughing. At minus 49 degrees Celsius, even your eyelashes freeze. "In exchange, you can drive across frozen rivers and the jewelry stores sparkle with all the diamonds mined there." His extra class, a daily Russian course, always began before sunrise. Admittedly, sunrise was at 10:30 am.

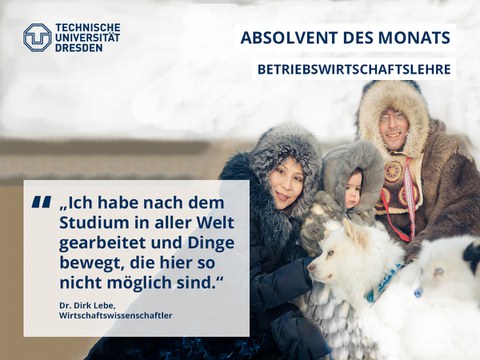

Dirk Lebe with his family in wintry Siberia

Dirk Lebe met his wife at a tram stop in Dresden. She comes from Yakutia, the very Siberian province where he taught, and which is nine times the size of Germany. It has a population of one million. She also studied at TU Dresden – medicine – and has spent the last few years traveling the world with him. Among other things, she has worked in Mozambique in the pediatric department of a hospital.

If you like chocolate, you will probably envy Dirk his last job: He spent four years working in the cacao sector in Indonesia. "Imagine, you eat heaps of chocolate for years and don't even know how cacao grows." That has changed, of course; he has trudged around a cocoa farm and had everything explained to him. And then planted a cacao tree in his garden. "Having absolutely free rein to do the job is something I've never experienced in Germany, and that's what's interesting about the job. You can make things happen that just aren't possible in the same way in Germany." The job was to provide training for cocoa farmers in a number of areas, such as tree grafting, nutrition, environmental protection, and finance. "Even if it's difficult to imagine, these are typical fields for development cooperation work. At the same time, you're in a position where you're balancing interests and also protecting farmers so they don't take on too much debt, for example," he explains. He worked for the Swiss NGO Swisscontact as a team lead for financing matters on this project, which is scheduled to run until 2020 and is training 165,000 farmers. "Environmental protection in particular is a sensitive issue when forests are cut down for oil palms, and in the past cacao as well. Fortunately, child labor is not as much of a problem in Indonesia as it is in Africa."

How cacao grows: pods on the tree

Part of Lebe’s job was also to document the origin of cacao to ensure that it did not come from deforested areas, and that prohibited pesticides had not been used in its farming. "The personal satisfaction that comes with a job like this is immense. As long as you're young, you should give things a try, and sometimes you get hooked," says Lebe. He has been living in Dresden again for a few months now, and is working on studies and project assessments in the field as a freelance international development cooperation consultant. It's not so much that he wants to put down roots, but "my wife has put her career on hold for long enough, now it's my turn. She can only do her residency in Germany."

Looking back over the last 15 years, he sees both advantages and disadvantages to living abroad. You rarely see beaches as beautiful as in northeastern Mozambique. Flying to Bali for meetings or conferences sounds more like a vacation than work, although there are much more beautiful islands in Indonesia than in Bali. And it’s not such a terrible thing when you're on a business trip, staying in a bungalow right by the sea, and then the airline cancels your only possible flight back and you're forced to stick around for another day. "For the kids, of course, it's great abroad. They grow up speaking four languages and don't even think about it." But in Africa, there might be no yogurt in the supermarket for two weeks, candlelight dining with your colleague loses its romance after three weeks with no power, and attacks by armed criminals, both minor and major earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions are new experiences that you could happily go without. Dirk Lebe was in Palu just before the recent earthquake. He was in the town until the early morning; the tsunami hit in the afternoon. He was lucky.

Who might have the skills for the area he has worked in?

Development cooperation can be a good field for engineers (e.g. water/wastewater), doctors (e.g. pediatricians or gynecologists), agronomists (and not only in tropical forestry, which is offered at TUD), traffic and transport specialists (congestion experts are probably the only people who would love the traffic in Jakarta), tourism students (ever heard of Flores or Toraja?) and in some cases also teachers (skills development is a huge field) – although not everything that glitters is gold. Organizations are often looking for university graduates, or people with many years of practical experience, for example in skilled trades. There are also projects for business management specialists. It helps if you try to broaden your horizons both before and during your studies. This could be by learning a new language, taking regional studies, or completing vocational training.

Dirk Lebe has never regretted his decision to go abroad. "You experience too much for regrets." And who knows where life might take him again in a few years...

Contact:

You can contact Dirk Lebe via LinkedIn – please include a brief message.