The mechanical engineer who became a winemaker

(Interview from 2001, with 2022 update )

Susann Mayer

Klaus Zimmerling holds a singular position amongst Saxon winemakers. Having studied Mechanical Engineering, he has now been making wine under the strict rules of organic production in Dresden-Pillnitz since 1992, but isn’t concerned with distinctions, preferring to sell it as a Landwein – a local wine, or vin de pays. In fact, famed wine expert Hugh Johnson has attested to the excellence of these high-quality wines. In December 2022, he celebrates the 30th anniversary of Weingut Klaus Zimmerling.

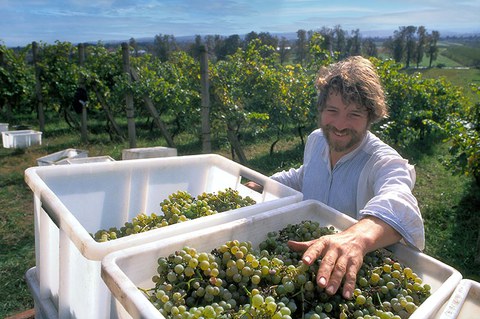

Klaus Zimmerling harvesting grapes

Tagesspiegel author Susanne Kippenberger described his wine as “unconventional” in an article in which the world of sommeliers discussed Saxon winemaking and in particular Klaus Zimmerling’s products. They mused over Saxony’s first organic winemaker, who began as an engineer and who presses a wine that “tells stories. Because you can taste where it comes from. Globalization has led to the impoverishment of viticulture. Suddenly, Chardonnay tastes the same wherever you source it – be it Californian or Australian. Like a bombshell. The wine from Pillnitz is not as bold. The wine from Zimmerling is as unconventional as the winemaker himself, whose 14-euro Riesling is still marketed as a Landwein ...”

Landwein is grossly understated, since its small but exquisite bottles offer select sips that have found their way into top restaurants in Dresden, Berlin and Leipzig. But for Zimmerling, it is pointless to succumb to the laws of wine bureaucracy. Official wine classifications such as Auslese (lit. “selected harvest”) or Kabinett (“cabinet,” essentially a reserve wine) specify where a wine is on the Oechsle scale, which denotes the must weight, or the weight ratio of sugar to water and thus the amount of alcohol that could be derived. These classifications also require certain amounts to be provided for laboratory testing. Contrarily, Landwein isn’t subject to such rigorous regulation. Zimmerling seeks to set his own bars. “My own expectations of the wines I produce don’t need classification,” Zimmerling explains dryly. “My prerogative is to sell wine that tastes good to ME. And my customer base has formed around that.” Not only this has garnered him the necessary attention to be able to live off of his winemaking – Hugh Johnson, perhaps the most highly respected wine writer, has also given Zimmerling’s wines his seal of approval.

Visitors are greeted at the entrance to the Zimmerling vineyard in Dresden-Pillnitz by sculptures created by his wife, sculptor Małgorzata Chodakowska.

Who is Klaus Zimmerling, the apparent eccentric who began producing primarily Riesling at the Königlicher Weinberg (Royal Vineyard) in the early 1990s?

The comes from a more technically oriented family of Saxonians. He initially followed in the footsteps of his father, a mechanical engineer for agricultural machinery, choosing to study Mechanical Engineering at TU Dresden. He later moved on to work as a design engineer. “It was a deliberate choice. I could see that there were better solutions for a lot of things in exterior design and operating principles, and I was eager to implement them.” It was during his studies that he first tried his hand in elderflower and cherry wine production. “However, I quickly reached a certain limit and really wanted to try out making proper wine from grapes – but not the kinds you could buy back then,” Zimmerling says looking back.

In the late 1980s, during his time as a design engineer, he leased a 600-square-meter plot of land at the vineyard in Wachwitz and began planting and raising grape vines. This allowed him to experiment. How do Traminer, Pinot Gris and Riesling develop in the Elbe Valley? Which vines survive the best in the unpredictable climate of Germany’s most northeasterly winemaking region? How can a good drop of wine be pressed with just the simplest technology? Zimmerling sought to find all this out through reading and experimentation. From self-teaching to application, he was always interested in maintaining his autonomy. “I’ve never handed a single grape over to someone else, preferring to grow them all myself; even if it was just a five-liter carboy,” he says proudly.

The era of glass carboys is long over. Today, Zimmerling ferments Riesling, Gewürztraminer and Kerner in modern steel vats in his cellar (located directly under the Pillnitz Palace). The cellar also houses wines fermenting in wooden barrels, including some vintages of Kerner.

Kerner is also grown on Zimmerling’s 4.5-hectare terraced vineyards in Pillnitz. He pensively looks out over the Rysselkuppe – a cone-shaped vineyard whose mineral-rich soil gives the wine its typical note. It is on this steep slope that he has been laboring away since 1992. It’s worth noting that he works without chemical fertilizers, instead preferring horse manure and horn shavings. Herbicides and pesticides are also taboo. “I don’t want to poison the soil or myself,” he says. An internship at the Nikolaihof winery in Austria in 1989 laid the foundation for his strict organic production. The year was a historical one for him in many senses. “Before the borders were opened, I had made many plans as a design engineer. Suddenly, the supply of everything was multiplied by 100. Plus, totally new job opportunities were available. And I met my wife shortly thereafter, who was studying in Vienna at the time. So the question was: Do I pursue a career as a design engineer in Austria or work at a winery?”

The wine labels feature images of Małgorzata Chodakowska's sculptures.

Zimmerling quit his job in Dresden and began working in the closest wine-growing area. In one year’s time, he traversed all aspects of winemaking with the aspiration of organic production. Acquiring his vineyard in Pillnitz in 1992 gave him that opportunity. He even sold his very first vintage, having pressed 3,000 liters’ worth. “I don’t view my degree and my current profession in contrast to one another. Right at the beginning, a professor said, ‘Studying is really nothing more than the ability to obtain and apply knowledge independently.’ And that’s what I’ve done,” he says. Today, he applies his knowledge to produce no more than 8,000 liters, true to his motto of quality over quantity. This means, for instance, that grapes which promise a greater harvest are not favored over the better ones – the manual task of sorting them out is much too laborious. Especially for a one-man operation like Zimmerling’s, which, after the first few years of beginner’s luck, had to overcome a dry spell in the mid-1990s.

“Back then, my wife Małgorzata wasn’t so confident in the career I had chosen for myself. It’s especially thanks to her work as a sculpture artist that we could stay afloat during that period.” Zimmerling’s labels feature a new wooden sculpture of hers each year. Whether thanks belong to mutual understanding or the connection between art and wine appreciation is for visitors to decide. Zimmerling’s vineyard is open for wine tastings. And who knows? Maybe you can learn more about the biography of the engineer who became a winemaker.

2022 update :

Two decades after this interview, work at the Königlicher Weinberg (Royal Vineyard) in Pillnitz has borne new fruit. A new cellar with a fermenting room has been built at the foot of the Rysselkuppe hill, with a press house situated directly above it. Decades of unwavering quality saw the vineyard honored with inclusion in the association for German quality wine estates, the VDP, in 2010. Since this time, the labels of the vineyard’s best wines feature classifications such as VDP.GROSSES GEWÄCHS® for dry wines or VDP.GROSSE LAGE® for wine made with grape varieties typical of the region. Moreover, the vineyard has been certified organic since 2020. Aromatic varieties such as muscatel and sauvignon blanc have been planted at the vineyard. For some time now, a sparkling wine made from pinot noir grapes has complemented the selection. This wine is fermented in the bottle and aged on the lees. With the opening of the vinothek and sculpture garden in the heart of the vineyard in November 2021, a very special place has been created for visitors to the winery to enjoy wine and art in harmony with nature. In December 2022, he celebrates the 30th anniversary of Weingut Klaus Zimmerling.

In October 2022, the winery was awarded the DNN Business Prize for the successful symbiosis of sculpture and winemaking, and a week of celebrations mark the 30th anniversary of Weingut Klaus Zimmerling.

Contact:

Weingut Klaus Zimmerling

Bergweg 27

01326 Dresden-Pillnitz

Tel.: +49 351 41394394