May 02, 2022

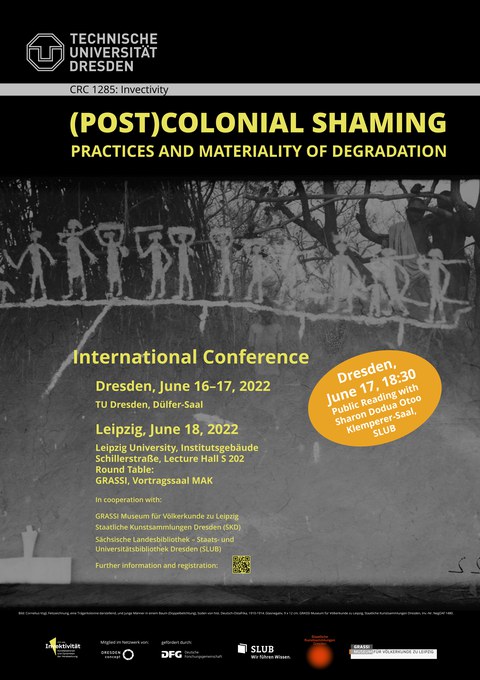

Update: (Post)colonial shaming: Practices and materiality of degradation

(Post)colonial shaming: Practices and materiality of degradation

Emotion-based practices such as shaming, humiliation, and discrimination were at the center of establishing and consolidating colonial power structures. Human actors did not only create positioning, group affiliations, and asymmetric coding within colonial contexts: things were also integral components of degrading practices during European colonialism of the late 19th and 20th centuries. Their materiality, for example, as commodities with every day or ritual-related uses, was put to a different use within such practices, loaded with new meaning or affected in various ways: weapons and traded (colonial) goods became, for example, vehicles for emotionally charged political strategies. Everyday things, ritual objects and art objects, and the architecture and infrastructures of a place/space, basically manifested traditional or newly configured power hierarchies. In addition to their content-related and aesthetic dimensions, images and texts were also part of degrading practices utilizing their material aspects - for example, in the form of photographic postcards. Objects of this kind with a colonial reference can still perpetuate shame today, for instance, through their use in educational and commemorative contexts, and repeatedly invoke them, as the current debate on restitution on the Benin bronzes shows, for example.

The delocalization of everyday objects removed from their cultural context of use and staged in colonial exhibitions in Europe provided these exhibits with a symbolic valence. It allowed the European audience to construct their cultural superiority. Images of people and things from the colonial areas assigned colonial roles to the colonized in European image and text media. This also gave meaning to the things that contributed to the establishment and consolidation of colonial rule. Photography in colonial contexts played a decisive role in producing a Western conception of the "primitive" or the colonial "exotic". Transfer processes and changes in meaning ultimately characterize the post-colonial survival of colonial things, people, power, and knowledge. Historically and/or culturally changing encodings do not eliminate each other but overlap and further shape the post/colonial' life of things'. This gives rise to a variety of problems in connection with colonial objects and references. From today's perspective, it should be discussed, for example, whether and how a non-degrading approach to things and practices seems possible, into which degradation through colonial use is already deeply woven.

This conference of the SFB 1285 "Invektivität. Konstellationen und Dynamiken der Herabsetzung" at TU Dresden aims to understand better how degradation, humiliation, and exposure as components of material colonial practices helped shape the colonial politics of shaming and as components of the cultural memory of all active cultural groups have perpetuated into the postcolonial present:

- Analytically, the conference examines emotional practices of degradation and the materialities involved with the concept of "invectivity". This brings together different abuse, shame, and degradation phenomena, which are understood as a form of communication that spans epochs and cultures. We are interested in the historical dynamics of colonial recordings and the delocalizations of colonial "found objects," including changed ascriptions of meaning, or reappropriation, for example, of "looted art" up to the post-colonial present. Utilizing interdisciplinary approaches, the connection between material things from colonial contexts and their function as media of invectivity, which has not yet been thematized in this form, is to be brought into focus.

- The question is discussed from a cultural-historical and museological perspective. On the one hand, the focus is on the possibilities and limits of a critical analysis of colonial practices with a view to an ethically appropriate, non-continually degrading handling of colonial "appropriations" of material or materialized objects. On the other hand, we ask about the possibilities of realizing the approach of a "shared heritage" (shared heritage) and its practical consequences. This ties in with current debates on discrimination and the culture of remembrance, which ask how societies can adequately deal with invective practices of past times accompanied by violence that is not characterized by ignorance, repression, and the continuation of colonial otherings.

- A link to register will follow in the coming days.