A "MedAk" alumnus shares his story

(Interview from 2014)

Susann Mayer

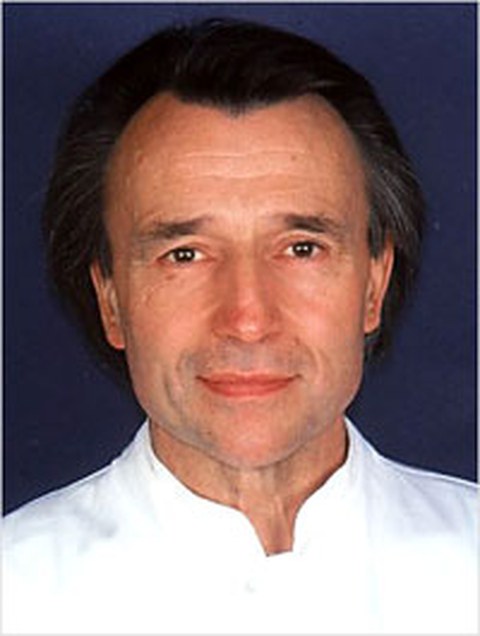

Gottfried Wozel – professor, alumnus and "co-founder" of the Faculty of Medicine 'Carl Gustav Carus' – is one of people who studied at the old "Medizinische Akademie" (Academy of Medicine) and also worked there for many years.

The main focus of his work was dermatopharmacology, on which he later wrote his habilitation thesis. In the early 1990s, he experienced the fundamental changes in medical teaching first hand, as he served on the founding commission of the Carl Gustav Carus Faculty of Medicine.

Kontakt spoke to Prof. em. Dr. med. Gottfried Wozel about his memories of that time.

Prof. Gottfried Wozel was a member of the commission behind the establishment of the Faculty of Medicine

Prof. Wozel, what made you want to study medicine, and why exactly did you decide to specialize in dermatology?

My choice was largely influenced by my mother, who was a surgical nurse in a frontline hospital during World War II. Later descriptions of her work always moved me when I was in school and reinforced my choice of career. With the option of studying at university after graduating from high school, my own clear decision was to work towards a medical degree. As a young medical student, my love for a given field was largely shaped by the example set by my superiors. That is why I started my residency in orthopedics under Prof. Hanns Büschelberger – a man whom I revered. Unfortunately, a short time later Prof. Büschelberger fell ill, so I lost my role model and with it my love of the discipline. That is why I switched to dermatology under the then head Prof. Heinz-Egon Kleine-Natrop, a major figure in his field.

What were the defining aspects of a degree at the Medizinische Akademie in the 1970s?

The three medical academies in the GDR – in Dresden, Erfurt, and Magdeburg – were solely responsible for clinical training. Preclinical training took place at existing universities. I did my preclinical training at the Humboldt-Universität Berlin, and then my clinical training, which I completed in 1971, at the "Carl Gustav Carus" Academy of Medicine in Dresden. Apart from the ever-present official political doctrine that pervaded all areas of life back then, I have distinctly positive memories of my time at both institutions; the training was practical with a strong clinical focus.

You have studied, researched, and completed your habilitation. Can you briefly describe your academic career?

A brief résumé:

- 1971: Start of my residency at the 'Medizinische Akademie' Dresden

- 1976: Qualification as a dermatologist

- 1978: Doctorate

- 1990: Habilitation [senior post-doctoral qualification] on experimental studies on the pathogenesis of psoriasis

- 1994: Appointment to C3 professorship in dermatology with a focus on dermatopharmacology

- 2010: Acting director of the Department of Dermatology

- Member of the founding commission (1991 to 1994)

- Dean of studies (1994 to 1997)

- Member of the ethics committee of the Saxon medical association (Landesärztekammer) since its foundation

- Member of various scientific and academic boards (societies, foundations, advisory boards, reviewer for scientific journals, book author/editor since 1996, and investigator in more than 60 clinical trials)

40 years of the Academy of Medicine came to an end in 1993. How would you describe the prevailing mood?

The era of the Dresden Academy of Medicine had officially become history with the ceremony celebrating the founding of the new Faculty of Medicine on October 25, 1993 – an important turning point for the history books. But there were still many unresolved details to be addressed. Appointment commissions needed to be selected rapidly so that the C4 and C3 posts advertised could be filled as quickly as possible. Many trial lectures had to be organized, and so on. As a result, the founding commission had to work well into 1994. Naturally, major changes caused concern, worry, and in some cases fear among a number of employees, which boiled down to a variety of key questions: Will my job still exist in the new structure? Will the number of permanent contracts be drastically reduced? What other unforeseeable consequences will the act restructuring higher education in Saxony (Sächsisches Hochschulerneuerungsgesetz) have?

The new structure meant, for example, that existing staff could not be retained exactly as they were in terms of quality and quantity. At the same time, social aspects could not be dismissed a priori. Overall, the underlying mood was initially one of uncertainty, with a degree of unrest, but not conflict. The situation was definitely not socially explosive. An overwhelming majority of employees looked to the future with optimism and enthusiasm as time progressed. The literal economy of scarcity had come to an end. Scientific ideas in clinics and institutes could be implemented much more quickly and easily. New partnerships began to emerge (e.g. the Rossendorf nuclear research center; TU Dresden institutes, etc.). Further synergies cropped up through the public health degree program.

Teaching today in the microscopy room

You were a member of the founding commission when the Faculty of Medicine was created. What specific tasks did you face?

In its recommendations of September 27, 1991, on university medicine in the new former East German states and Berlin, which had just been reunified with the rest of Germany, the German Council of Science and Humanities stated that Dresden and Leipzig would also be well suited to host a university hospital in the federal state of Saxony. However, it did not recommend the continuation of the Medizinische Akademie Dresden (Dresden Academy of Medicine). A realistic goal was, however, a genuine new beginning with the establishment of a faculty of medicine at TU Dresden. Then State Minister for Science and the Arts, Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Meyer, quickly appointed a founding dean from the University of Würzburg – the neurosurgeon and professor emeritus Dr. Karl-August Bushe – and other members of the commission, which held its first and constitutive meeting at Wachwitz Castle in December 1991. Incidentally, this was the time at which the necessary legal framework was being created in Saxony (i.e. the Sächsisches Hochschulerneuerungsgesetz or SHEG, the act restructuring higher education in Saxony, of June 21, 1991). It is against this backdrop that the main tasks facing the founding commission must be considered: developing proposals for the faculty structure, deciding on staffing requirements and defining/describing material requirements (see also § 127 SHEG). From today's perspective, that sounds simple, almost trivial, but at the time it was – though not immediately clear – an immensely challenging task, especially since we were not starting from scratch. Existing staff, buildings, etc. had to be integrated into the new faculty. The time and logistical effort required were immense.

What were the greatest achievements in this period of upheaval?

For me, the most visible and symbolic representation of the new faculty was the new Medical-Theoretical Center (Medizinisch-Theoretisches Zentrum – MTZ) building. A lot of detailed planning, such as floor plans and material catalogs, had gone into its development. Retaining the dentistry department was another major success. For me personally, the entire period on the founding commission was by far the most compelling, interesting, and instructive part of my academic training. Overall, it was characterized by an extraordinary will to create something new and lasting. The results are clearly evident today.

Does everyone in the Johannstadt district faculty now feel truly at home in TUD?

I would like to turn that question around. TUD is now at home in the Faculty of Medicine 'Carl Gustav Carus' with its 4000 employees in Johannstadt.

Contact details:

TU Dresden

Faculty of Medicine 'Carl Gustav Carus'