A few questions for a former "PH" student

(Interview from 2014)

Susann Mayer

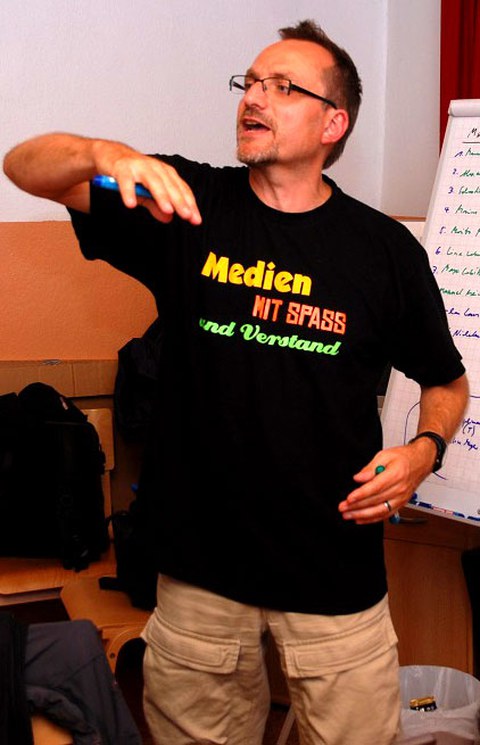

For many years, Andreas Edhofer was a successful self-employed manager for a wide variety of educational projects. Today, he is employed as director of Opferhilfe Sachsen e.V. and works part-time in the partnership "Edhofer & Partner, Medien- und Sozialpädagogen".

As part of its broader profile, the partnership runs Saxony's film and media camps and manages various camps for schoolchildren, which focus on career choices and boosting academic success. Edhofer began his studies in 1990 at what was then the Pädagogische Hochschule (PH) (College of Education) and graduated in the mid-1990s from the Faculty of Education at TU Dresden. In other words, he experienced major changes in the education system and teacher training firsthand.

Kontakt spoke to Andreas Edhofer about his memories of that time

Andreas Edhofer

Mr. Edhofer, what made you decide to study education?

It seems like something of a miracle to me that I ended up doing so in 1990. That had a lot to do with my socialization and the upheaval in the GDR. At an early age, I had wanted to become a teacher or a nurse – in other words to do a job that involved working with people. However, my own difficulties with the institution of school and rigid state requirements, and the lack of direction I often felt as far as my own life was concerned, meant that there was little chance for someone like me at that point to enter an education profession. So, first I did what my father told me (become a toolmaker), and then I tried my hand as a fitter, technician, and so on. Shortly before and during German reunification, I had the idea that I could shape the country and make an impact for the better, but I soon realized that I was not born to be a political militant. I'm too much my own man for that; I didn't submit to authority well and couldn't keep my mouth shut. In 1989, I got the chance to become a cultural association/club manager by studying at the Fachschule Meißen-Siebeneichen vocational school. At last, in the midst of the political upheaval, I was able to engage on a deeper level with cultural, social, and educational questions. However, I quickly realized that a qualification from that school offered only limited career options in a reunified Germany.

At the same time, I had somehow managed to obtain my high school leaving certificate. Vocational training with a high school diploma ("Berufsausbildung mit Abitur") was the GDR’s magic formula that made that possible – today, by the way, it is often talked about as a "new" idea. All those who had graduated from the vocational school in Meißen therefore had the option of switching from vocational school to a university education. Some graduates went to the West; I chose to study cultural education at PH Dresden. At PH Dresden, we were able to get involved in practical media education projects at the audiovisual center, for example. That's how I got into media education at an early stage.

However, the program was soon to come to an end in Dresden. As I recall, the view was that one program – in Hildesheim – was enough, and in terms of education policy, there was a reluctance to run education degree programs with most of the "old" higher education lecturers, who had been "close to the regime." So, cultural education courses soon stopped, and we students got a new chance to continue our studies in education with a focus on social pedagogy at TUD.

For a long time, I resisted being drawn into the social pedagogy field, for I had always associated that area with helper syndrome. However, those years turned out to be very constructive, and I launched straight into a university career. It's a good thing I later ended it. I realized that I can plan, structure, and lead well, but am not a researcher or academic. And if you know that you are not a politician and not an academic, then you are completely out of place in the current higher education landscape.

The logo of PH Dresden in 1989

What was distinctive about studying at PH?

At that time, there was a feeling of change and excitement everywhere. Finally, you could study what you wanted, engage with any and all issues, take a whole lot of inspiration from clever and experienced minds, and turn a lot of things on their head – it was great. I have great memories of the many opportunities I had to try out my practical skills alongside my studies, for example working in groups, presenting my own thoughts, and designing and implementing projects with school students. Even my part-time student jobs afforded me a wealth of life experience. Despite all that went on and all the uncertainty, I never felt like I was being abandoned; that I was being offered new options. We always had the chance to give our input, to be taken seriously, to make mistakes. Of course, we felt we had a lot of power as students at that time; some of my fellow students had already lived quite an independent life, as I had.

I also remember easy opportunities to travel abroad with fellow students. A visiting professor from Norway once quickly organized a trip to Oslo – simple, but full-on. Others later went to the USA...

You now work in media education with children and teenagers. How does what you studied help in your current role?

I learned something fundamental during my studies: I need be interested in something. Only then can I truly perform and achieve, solve even the most difficult problems, and forge a new path. How often was I really interested in something during my schooling? How often at school did I find myself at a loss when I asked myself why a subject was necessary or useful? How often did I fail to absorb something that I could not connect to? Then, in projects like the film camps, I got to know young people who were facing exactly the kind of problems I had had. I was able to apply my knowledge to design projects that are true to life, to create the right learning environments, and to build camaraderie in the relationship between learners and teachers, for example. With a graduate scholarship, I was also able to work on my doctorate in historical social pedagogy. Exploring the archives, discovering connections in the material myself and then presenting them to others also gave me great satisfaction. But I wanted to be a lecturer, not a university expert on external funding. I wanted to work with people, not swear to the knowledge in some illustrious circle of initiates. I didn't want to be dependent on things that did not interest me. That's why I later left university.

During the "Sächsische Medienakademie" (Saxon media academy) with young people on the River Elbe

Since 1991, I have successfully organized a number of projects with thousands of children, teenagers, and young adults, mostly in the role of camp or project leader. I have organized and run symposia in various fields. I was self-employed from 2004 to 2011, have been instrumental in developing a victim support organization for over ten years now, and work on education project design and implementation for various providers. I hope that I can continue on this path in the years to come.

I would not have achieved all this without my studies and the sometimes tortuous paths I took during my time at TUD. The confidence that I need every day, and the authenticity without which any success is short-lived, have emerged from the foundations laid during my university days. Again and again, I have hit my limits or gone through deep emotional dips, but my desire to find out more and try out new things has persisted.

Decades of "PH" history came to an end in 1993. How would you describe the prevailing mood at the time?

A spirit of optimism; a fresh start, as I described above. My path lay ahead of me and I was able largely to shape it myself, and was consistently encouraged and supported. I had a young family, and my wife at the time was also at university. Life was all about Dresden and studying. Nowadays, I live far away from the big city; I need a lot of space, peace and nature to cope with the stress of work – the daily rat race. When you work with people, you need an inner peace or a sense of security in your family, with friends and good colleagues. Otherwise, you can't do your job without damaging your health.

What were your greatest achievements in this period of upheaval?

I just managed to earn my high school diploma. My grades at the end of my fundamental studies in psychology weren't that great either, but ultimately I ended up being one of the best students and got the graduate scholarship – and now, I benefit from that route. Unfortunately, my view of that time is also a little bitter. To me, a lot of things just didn't really move forward. The spirit of optimism around the time of reunification quickly died. A lot of things once again smelled of the GDR to me. There were few real career or other prospects for graduates of the university, and the quality of courses got worse. Increasingly, there were too many students, the general environment seemed to deteriorate, and there was a growing lack of motivation on the part of students. I went to a lecture at the university a year ago and had the impression that nothing has changed in all these years. Even if the impression is not objectively accurate, this subjective view still makes me think I did everything right.

What else would you like to share with readers?

I tell my eldest daughter this all the time (to no avail): I think it's generally a good idea if you learn a profession before studying or, alternatively, volunteer or spend time abroad to broaden your horizons and become more independent. Exceptions confirm the rule. That's why I think, all right, she (my daughter) is a graduate psychologist at the age of 23... I have expressed my concerns often enough. They need not apply to her. I will never reproach her if she – later – comes to the same realization. I will not dictate my three younger daughters' path either...

Thank you for your detailed and very personal retrospective, Mr. Edhofer.

Andreas Edhofer (right) in conversation with Daniela Schadt (2nd from right), patron and chairwoman of the board of the German Children and Youth Foundation

Contact details:

Edhofer & Partner, Medien- und Sozialpädagogen

Andreas Edhofer

Email: Andreas Edhofer