Inclusive political education - initial situation, challenges and goals in the "Designing inclusive schools" project

Table of contents

Abstract

The SING project also aims to explore how political education can succeed within schools in such a way that it is interesting for everyone in their own way, enables everyone to make an independent judgment on questions of coexistence and to intervene in the shaping of common coexistence themselves. The aim is to address the needs of all pupils as well as the most important content and topics of the subject. To this end, the project will work with students in schools to research models and methods that could enable such political education. To this end, instruments must be developed that allow the individual needs of individual pupils to be made visible with regard to the content of civic education and individual learning requirements, and concepts must be tested that enable inclusive civic education. To this end, TU Dresden is cooperating intensively with schools and teachers in Saxony in order to jointly develop new approaches on site.

Find out more

If you analyze the discourse on inclusion, you quickly get the impression that this is a very broad - almost unmanageable - field. Due to the popularization of the term "inclusion" as a public buzzword, an increasingly far-reaching, blurred use and even "neglect of inclusion" seems to be progressing (Katzenbach 2015, p. 19).

It therefore comes as no surprise that the discussion about inclusive political education, which has been ongoing since 2014, has not yet produced a uniform understanding or well-founded concepts for inclusive political education. In 2015, the Federal Agency dedicated itself to the topic more broadly for the first time under the title "Didactics of inclusive civic education" (Dönges/Hilpert/Zustrassen 2015). The focus here is on articles on inclusive civic education in schools (e.g. Weißeno 2015, Richter 2015) and on dealing with people with disabilities (e.g. Schiefer/Schlummer/Schütte 2015, Hufer 2015). Overall, most of the articles deal with questions of didactic approaches, dealing with specific target groups, the suitability of conceptual elements such as language or media or specific content and skills for inclusive civic education. In summary, the focus is on questions of inclusive political teaching and learning processes, often for people with disabilities in the school context. Here, we will briefly discuss the current state of the discourse on inclusive civic education and show why a consistent, exclusion-sensitive and subject-oriented perspective is required that does not lose sight of the subject of civic education. In this context, the goals of the SING project with regard to inclusive civic education will be presented.

Initial situation - thinking inclusion as transformation

In the broad debate on inclusion (e.g. Wocken 2015, 59f), it is often pointed out that inclusion can ultimately only be thought of as a transformation and change for society as a whole, as the idea of equality in all diversity can only exist if it is not limited to the field of education (Dederich 2014). A lacking or narrowed transformative view of the overall inclusive process that is also geared towards change is therefore often the reason for the failure of attempts to implement inclusion (Booth 2012).

So inclusion is a process of change? But who is it about? The question of who inclusion affects can be answered narrowly by focusing on people with disabilities. Or it can be broadened to include other people with participation difficulties: People of different cultural or social backgrounds, people of different sexual identities or orientations, of different ages, etc. Ultimately, however, it can also be argued that this must involve all people, as it is also about changing the thinking and actions of those who are not excluded in certain contexts (Jugel 2015).

The question remains as to what the goal of inclusion should be. A wide variety of answers can be found here. In this context, there are repeated calls for accessibility, access, justice, reduction of discrimination, etc. (Jugel/Hölzel 2016). It makes sense to summarize these terms under participation or inclusion, as all other goals are either a prerequisite or an elementary part of participation or inclusion. This results in the following concept of inclusion: inclusion is a transformation process for society as a whole that aims to enable participation for all people (see Jugel 2015).

Based on this, however, the question arises as to what such a process of change can look like in the practice of political education in schools and what conditions and dimensions it is subject to.

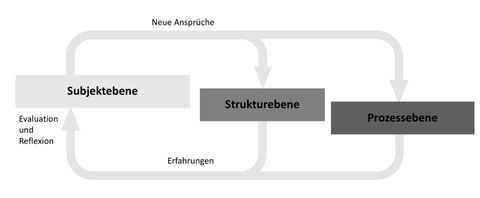

Empirical findings from participatory and design-oriented research were able to identify such dimensions and initial hypotheses about their nature. Hypotheses about the need for change (see Jugel 2015) were empirically tested in an iterative process, differentiated and summarized in a transformation model (Jugel/Hölzel 2016). The model consists of three levels: a subject level (the actors), a structural level (the framework conditions) and a process level (the planning and implementation of political education programs).

The SING project will primarily address the challenges of planning and implementation, i.e. the process level of inclusive civic education. Nevertheless, the subject and structural levels must always be included as important boundary conditions.

Challenges at the process level of inclusive civic education

The planning and implementation of civic education is often perceived by teachers as the greatest challenge. This is attributed to the "unknown" - not knowing how to deal with this or that pupil. On the one hand, there is often a lack of diagnostic skills (this is not about the ability to identify specific clinical pictures or deficits, but rather the ability to identify individual needs) and, on the other hand, the knowledge of how to respond appropriately and adaptively to diagnostic findings (Besand/Hölzel/Jugel 2018). If this is to succeed, projects and learning environments must be designed in such a way that they are flexible and can be adapted to the individual needs of each participant at any time (ibid.). However, this is often countered by widespread planning dogmatism - a teaching unit is good the better it has been planned and the more faithfully it has been implemented. However, if individual needs cannot be met, participants quickly find themselves in isolating conditions or isolation (Jantzen cited in Steffens 2016). The consequences can be various compensatory actions, which can initially manifest themselves in the form of withdrawal, aggression or self-stimulating behavior (e.g. nervous tilting, fidgeting or tapping) (Steffens 2016). However, all of these reactions are widely perceived not as a reaction to exclusion, but as a disorder (Störmer 2013). Not to do this, but to act adaptively, is extremely challenging. At the same time, it is evident that both teachers and subject didacticians find it difficult to reconcile the individual needs of learners with the topics and content of civic education (Besand/Hölzel/Jugel 2018). Starting points for individualization, differentiation and methodological considerations that deal in particular with heterogeneous learning starting points have so far only been presented in the margins of various approaches in the discourse on civic education (e.g. Frech et al. 2010; Ziegler 2009; Kühberger/Windischbauer 2013). The discourse has yet to provide a solid theoretical and empirical foundation for civic education in heterogeneous learning groups. However, the first empirically based approaches for inclusive political learning can be found in the results of the project "Inclusive political learning in the stadium" (Besand/Hölzel/Jugel 2018). The first important principles for the success of inclusive political education processes and approaches for situational and targeted diagnostic processes in this context are presented here. What is missing, however, are concrete and tried-and-tested tools that can be used to identify individual needs. In addition, there is a need for techniques and competence descriptions that describe the transfer process between individual needs and concrete planning decisions as well as practical routines for inclusive civic education.

Project goals regarding inclusive civic education

The aim of the SING project is to fill these gaps. The aim is not purely evacuation research, but a development-oriented, participatory and cooperative approach that takes place between the training of teachers at university and the practical field of "school". In this way, student teachers and teachers should be sensitized to heterogeneity and exclusion and acquire developmental and diagnostic skills. With the help of these skills, they will independently develop diagnostic tools for inclusive civic education, which they will test and further develop directly in school. At the same time, they acquire skills in empirical research methods. The results of the diagnostics provide the basis for the planning and implementation of inclusive lessons in the subject "Community Studies" (civic education). Teachers at the schools are also sensitized and involved in this process. Ultimately, this implementation is evaluated and forms the basis for further developments and modeling for instruments and theories of inclusive civic education.