A

Table of contents

A

Achim (Komturei, Deutschland)

See Tempelachim

Affiliation

See Donaten

Agrippa von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius

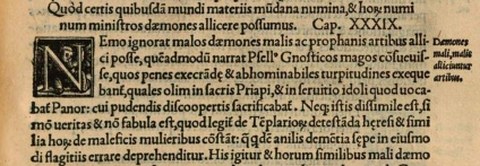

The German scholar, alchemist, physician and soldier (1486-1535) was highly interested in the history and practice of magic and the occult, especially the Hellenistic writings of Hermes Trismegistos, who was considered the 'father of alchemy'. In his work De occulta philosophia, written around 1510 and printed in 1531, he set himself the goal of distinguishing between the "good and holy science of magic and the evil, scandalous practices of BLACK magic" and saving the reputation of the former as black magic banishes demons and seeks to harness their powers. As examples from history, Agrippa mentions the Gnostic magicians who continued the cult of Priapus and "so that what one reads is the truth and not a fable" - the Templars, as well as the witches.

Author: Anke Napp

The passage in question in the Cologne print

Sources for this article and further reading:

Henrici Cornelii Agrippae ab Nettesheym: De occulta Philosophia: libri tres, Köln 1533, Lib. I, Cap. 39. Online

Acre (Commandery, Palestine)

The ancient port and trading city, which was also to gain inestimable importance for the economy of the Crusader states, was conquered in 1104 in a joint operation on land and sea by Genoese, Pisans and troops of Baudoin I of Jerusalem, and remained in Christian hands until shortly after the Battle of Hattin in 1187. After a siege of over two years, it was retaken in July 1191 by the combined forces of the besiegers, including King Guido of Jerusalem and Richard 'Lionheart' of England.

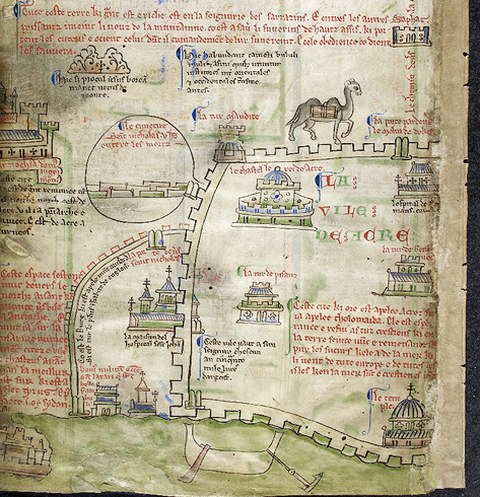

Acre on a Holy Land map in a manuscript by Matthäus Parisiensis. Below right the seat of the Templars, left within the two walls the seat of the Ordert of St. John, left of the camel the "Tour maudite".

After the fall of Jerusalem, the branch in Acre became the Templars' main house. The castle was located on the sea side - nothing remains after the slighting and removal of stones by the townspeople. The commandery was not only of military and administrative importance, but was also an important religious centre for the population of the region. The notary Antonius Sicci reported in his testimony during the trial before the papal commission in 1311 that the order had housed a relic in its house in Acre - a copper cross, supposedly made from the tub in which Christ had been bathed - to which miraculous properties were attributed. It was carried through the city in processions by the patriarch and the Templars and proved its power especially in prayers for rain. Miraculous healings also took place in the Templar church of Acre.

Discovered in 1994, the tunnel, over 300 metres long, connected the Pisan trading post with the Templar warehouses. One branch reached as far as the port. This was the way the Templars imported their goods, which were tax-free (due to the various privileges).

Acre also played the leading role in the last act of the drama of the Crusaders in the Holy Land. The Master of the Templars, Guillaume de Beaujeu, had initially negotiated with Sultan Kalawun of Egypt for the ransom of the inhabitants of Acre - but the latter proudly and complacently refused.

The Mamluk army that consequently assembled in front of Acre in the spring of 1291 under the leadership of Sultan Kalawun's son Khalil consisted of 100,000 - 200,000 soldiers, about 40,000 of them cavalrymen (and thus outnumbered the defenders in the city by a factor of 20) and was determined to take the city.

On 5 April 1291, the siege of Acre began. At first, the situation was not even hopeless for the defenders. A few small breakouts were victorious and a relief army from Europe was expected. On 4 May, the King of Cyprus actually appeared in the city's harbour with 40 ships. A final negotiation initiative failed when a Christian catapult projectile fell next to Khalil's tent just as King Henry of Cyprus was about to negotiate the terms of the surrender.

From then on, there was no doubt that the siege would continue to the bitter end.

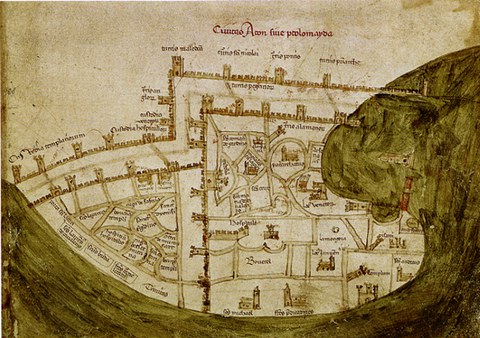

Acre had a double ring of walls with towers, which the Mamluks tried to weaken by undermining them. At the same time, siege engines were deployed, and by mid-May the first towers collapsed at their weakest points. The members of the Order of St John and the Order of the Temple performed heroic deeds in beating back the invading attackers.

On 18 May 1291, the besiegers succeeded in taking the strategically important so-called "Tour maudit". In an attempt to retake the tower, the Master of the Order of the Templars Guillaume de Beaujeu was mortally wounded, causing chaos and panic among the remaining defenders. Those who had not managed to get onto one of the ships in time and thus flee the city were killed by the invading soldiers of Khalil. As with the conquest of Arsuf and Caesarea in the sixties of the 13th century, and later Antioch and Tripoli, hardly any prisoners were taken.

The Templar fortress, where many civilians had taken refuge, held out the longest, while the rest of the city was already occupied and looted. The leader of the Mamluks offered an 'honourable surrender', which the marshal of the order, Pierre de Sevry, accepted. But no sooner were the Sultan's first soldiers inside the fortress than, contrary to the agreement, they began looting and raping the women - the result was that the Templars massacred the delegation. Another offer by Khalil to negotiate with the marshal turned out to be a trap: Pierre de Sevry and his escort were executed. Also on 18 May, the keep of the fortress collapsed as a result of mining operations undertaken, burying both the defenders and a large number of the Mamluk attackers.

Numerous chroniclers who report on the fall of Acre pay tribute to the Templars' efforts in the city's final hours, including the Austrian Reimchronik, the Chronicle of S. Petri in Erfurt, Thaddaeus of Naples as well as Giovanni Villani.

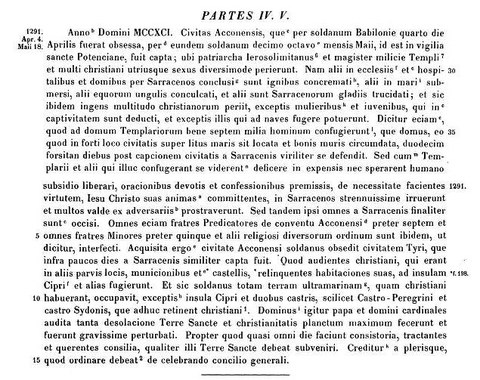

Report of the fall of Acre from the Cronica S. Petri Erfordiensis

Acre, plan from: Marino Sanudo, Secreta fidelium crucis, 14th century (London, British Library MS. Add. 27376, fol. 190r). The individual assigned guard sections can be seen, such as the 'custodia Templariorum' on the left, the 'Tour maudit' at the top centre.

Sources for this article and further reading:

Sources:

- Cronica S. Petri Erfordiensis Moderna, ed. O. Holder-Egger, in: MGH Scriptores 30,1, Hannover 1896, pp. 335-457, hier p. 424f. (Text online)

- Thaddeus of Naples: Hystoria de desolacione et conculcacione civitatis Acconensis, ed. Paul Riant, Geneva 1873, p. 19.

- Michelet, J. (ed.): Le Procès des Templiers, 2 Bde, Paris 1841, Bd. 2, pp. 642-647 (original).

Literature:

- Barber, M., Bate, K. (eds.): The Templars. Selected sources translated and annotated, Manchester 2007, pp. 115-117 (english translation of the Latin text).

- Gabrieli, F.: Die Kreuzzüge aus arabischer Sicht, Augsburg 1999, pp. 407-414.

- Nicholson, Helen: Love, War and the Grail, Leiden-Boston-Köln 2001, p. 228.

- Wieczorek, Alfried: Der Fall von Akkon 1291. In Wieczorek, Alfred, Fansa, Mamoun, Meller, Harald (eds.): Saladin und die Kreuzfahrer. Begleitband zur Sonderausstellung, Mainz 2005, pp. 455-458.

Albenga (Commandery?, Italy)

Templar property in the Albenga area was first mentioned in 1143 in a donation. The branch probably did not yet exist at that time. The donation, and also one in the following year, were accepted by a donat named Oberto, referred to in the documents as missus de Templo. Further donations from the citizens of Albenga followed in the years to come, and in 1167 the settlement, together with the church and all the property belonging to it, was leased by the acting Provincial Master to the donat Robaldo Marabotto and his wife, who had previously donated further land to the Order. Robaldo administered all the property and also accepted further donations with full authorisation. From 1179 onwards, ministri (this may be the term for commanders) of the settlement are mentioned. In 1191 almost all the property in Albenga was sold to the local bishop, and the house itself was leased to him. At that time, five friars lived in the branch, including a priest.

The commandery's church was dedicated to the local saint, S. Calocerus. Some researchers identify it with the present-day church of San Giorgio, which, however, belonged to a Benedictine monastery.

Komture

1167-1179 Roboaldo Marabotta

1179-1182 ministri Guglielmo di Vignano u. Guido

1186 minister Enrico

Albenga, 17031 Albenga, Savona, Italien

Sources for this article and further reading:

- Bellomo, Elena: The Templar Order in North-West Italy, 2007, pp. 229ff.

Albigensian crusade

see Cathars, relations of the Templars with