Attachment and relationship and why this is important in political education

Emotions and political education? Emotional and heated debates in politics and society often seem unhelpful enough, don't they? So why should emotions also be consciously considered and incorporated into political education? And on the other hand: is that even possible? Political education without emotion? This impulse outlines why precisely these emotions are important in all learning and negotiation processes and must therefore also be consciously considered and included in political education. It poses precisely these questions and discusses them against the background of the subject of political education as well as the learning processes of political education.

It must be noted at the outset that the idea of a purely rational civic education focused on imparting knowledge, which ignores emotions and feelings, is still widespread (both in the field of civic education as well as in practice) and often seems to be the more appropriate or even more sensible form of civic education.

Since the term "emotion" is a particularly diverse and frequently used term, it seems essential to begin these considerations with a brief clarification of understanding: Emotions are understood here as states with which people react to external conditions. (Hölzel, Jugel 2019). "Positive emotions (...) give us the orientation to stay on course and continue exploring the environment, while negative emotions cause us to make adjustments to our current situation" (orgi. in german by Gozolino 2007: 97f). This insight is of particular interest for civic education, as it is associated with a specific responsibility that is not equally important in other areas of education. With approaches that are close to the real world and its socio-political subject matter, civic education often addresses particularly close, personal and life-centered topics, which are therefore often perceived as particularly emotional. If we understand in this context that emotional experiences continually influence current perceptions, decisions and actions with a view to the expected future, we must devote significantly more attention to emotions in civic education (Hölzel, Jugel 2019).

Two aspects in the context of emotions and civic education will therefore be discussed anew here:

- The (in)separability of ratio and emotio (people experience everything in an emotional-cognitive way - emotion and cognition cannot be separated in experience). (Hölzel, Jugel 2019) and beyond that

- the special importance of emotions as a basic prerequisite for political learning and not as a disruptive factor to be eliminated.

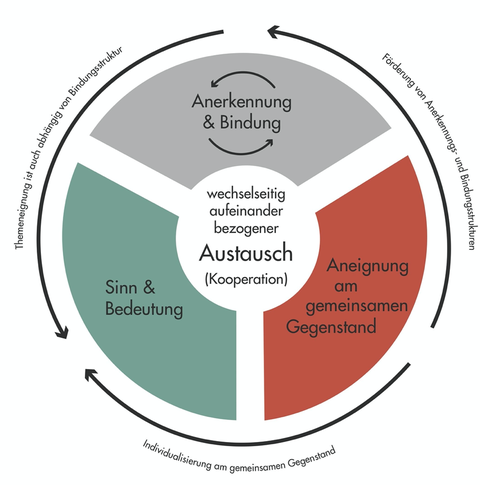

Consequently, it is crucial to show that emotions play a central role in the context of learning in general and thus also in political learning. Above all, attachment takes on a special significance in the context of didactic discourses,

- that just as ratio and emotio cannot be considered separately from one another,

- the subject matter of civic education, i.e. the content and topics, cannot be detached from the emotionally shaped previous experiences with these political subjects and the social relationship structures (attachment).

- as well as the social relationship structures (bonding) of groups in which these learning objects are negotiated,

cannot be treated separately from each other (Hölzel, Jugel 2019). However, since the subject-didactic discourse has so far focused strongly on the learning objects and the general and special education course on the learners, there has been a consequential responsibility gap or blind spots at the interface between the two fields, in which subject didactics has been thought of without emotional questions.

In view of the above, the question of the subject-object relationship must therefore be fundamentally re-examined for political didactics. If emotions are the central mediating point between the learner and the subject of didactic learning, then political education must pay more attention to the emotional constitution of learners and develop appropriate instruments that enable political learning in accordance with individual prior experience and the specific learning group.

Emotions, interaction, attachment and recognition prepositions, meaning and meaning structures must become a central part of subject-specific didactic models (Hölzel, Jugel 2019).

In practice, this means that for diagnostics, not only must the needs of individual segments - such as interest, appropriation skills, attachment structures and previous emotional experience - be assessed holistically, but everything should be considered in the context of their interwovenness with the chosen learning objects. This requires not only the development of appropriate practical skills, but also the time to be able to carry out such diagnostics. Neither outside of school nor in the classroom has this need been fully met to date.

A closer look at the empirical evidence has shown that political topics that are close to real life are also those that are considered by learners to pose a risk of retention. This is particularly problematic in the case of unknown, new or conflict-ridden groups and hinders the learning process. For this reason, the first topics to be discussed should be those that do not endanger bonding, but on the contrary promote the development of bonds within the group itself and with the practitioners. These can and should still be topics related to the real world, but in a more exemplary form and based on less confrontational topics. Students often mention topics such as "peace" and "mutual support" (cf. Besand, Hölzel, Jugel 2018: p. 89) For example, "peace" as a topic can clarify how conflicts can be overcome without having to deal with a conflict that directly affects the participants' lives. If, at the same time, a bond can be created using appropriate methods, above all by incorporating cultures of recognition and initiating processes based on cooperation and division of labor rather than competition, then a safe environment and a good bond within the group and with the team leaders will increasingly develop, which will also allow conflict-laden topics close to the participants' lives to be discussed.

In addition, further requirements can be formulated from the theses in the article. Although this article focuses on discussing and analyzing the importance of emotions for the pedagogical and didactic success of civic education, the observation that cognition and emotion are inseparable also applies to the subjects of civic education. Pseudo-objectification and the attempt to de-emotionalize political education can therefore only lead to more difficult learning processes and thus a distortion of approaches. It is not enough to deal with the social consequences of fear and anger in political education - for example in the form of political radicalization or violent conflicts - but a materialistic examination of the contexts in which such emotions arise is also required in order to be able to discuss and evaluate adequate options for action and political action. This results in an urgent postulate for the discourse of political education: emotions and their constitutive contexts must be given more space in the curricular subject area of political education.

Finally, reference should also be made to another central aspect of the findings of the accompanying study on inclusive civic education, which could only be presented within the student statements outlined here. It was shown that emotions and commitment are of central importance for the field of didactic research. The use of participatory research and the design-based research approach made it clear that a secure bond between researchers and co-researchers (in this case the educators) is of central importance for the sensitization and qualification of political educators as well as the joint interpretation of data and the development of practical instruments and strategies. The two-year participatory accompanying studies have shown no less clearly how important a good bond is, especially with young participants in political education programs who have had a variety of experiences of exclusion, if you want to receive honest and constructive suggestions from them in interviews (see also Hölzel 2018). If an openness is to be achieved that turns the research process into a learning opportunity for everyone, greater consideration must also be given to emotions and attachment in the context of research and evaluation methodology.

In summary, it can be said that a change of perspective and paradigm is required if political education (even in times of increasing social fragmentation and political polarization) is to create adequate offerings that enable all people to participate. Emotions are fundamentally important in all areas of political didactics - i.e. its research, its theories, its recommendations for action and its practice - and require more attention.

You can find a collection of methods for building attachment here on this page.

Literature / further reading

- Besand, Anja (2016): On the relationship between emotionality and professionalism in political education. In: Heinrich Böll Foundation (ed.): Ideologies of inequality, Berlin, pp. 77-83.

- Besand, Anja; Hölzel, Tina; Jugel, David (2018): Inclusive political learning in the stadium - political education with an unknown team and an open course of play, [Weiterdenken - heinrich-Böll-Stiftung Sachsen] Dresden. Available at:

- Damasio, Antonio R. (2013): The Spinoza Effect. How feelings determine our lives, Berlin.

- Euler, Dieter (2014): Design Research - a paradigm under development. In: Euler, Dieter/ Sloane, F.E. Peter (eds.): Designed-Based Research, Stuttgart, pp.15-44.

- Feuser, Georg/Jantzen, Wolfgang (2014): Attachment and dialog, In: Feuser, Georg/Herz, Birgit/Jantzen, Wolfgang: Emotion and personality, Stuttgart, pp. 64-90.

- Fischer, Kurt W. (2008). Dynamic cycles of cognitive and brain development. Measuring growth in mind, brain, and education. In Battro, A. M./Fischer.K. W./ Léna, P. (Eds.), The educated brain,. Cambridge U.K. pp. 127-150.

- Gessner, Susann (2014): Political education as a space of possibility, Schwalbach/Ts.

- Grammes, Tilman (1998): Kommunikative Fachdidaktik - Politik - Geschichte - Recht Wirtschaft, Wiesbaden.

- Gozolino, Louis (2007): The neurobiology of human relationships, Kirchzarten.

- Heidenreich, Felix (2012): Attempt at an overview: political theory and emotions. In: Ders./Schaal, Gary (eds.): Political Theory of Emotions, Baden-Baden: 9-28.

- Henkenborg, Peter (2013): Civic education for democracy: learning democracy as a culture of recognition. In: Hafeneger, Benno; Henkenborg, Peter; Scherr, Albert (eds.): Pädagogik der Anerkennung. Foundations, concepts, fields of practice, Schwalbach/Ts., pp. 106-131.

- Herz, Birgit (2017): Emotion and personality. In: Feuser, Georg/Herz, Birgit/Jantzen, Wolfgang: Emotion and personality, Stuttgart, pp. 17-37.

- Hölzel, T./Jugel, D.: "You can lose friends there!". Political education, emotions and bonding - clarifying a didactic error. In: Besand, A./Ovewrwien, B./Zorn, P. (eds.): Political education with feeling. Bonn: 2019, p. 246 - 266. ( free download here)

- Jantzen, Wolfgang (2010): General Disability Education, Volume 1: Social Science and Psychological Foundations. Weinheim.

- Jantzen, Wolfgang (2012): In the beginning was meaning. On the natural history, psychology and philosophy of activity, meaning and dialog. Berlin.

- Petri, Annette (2018): Emotion-sensitive political education. Consequences of emotion research for the theory and practice of political education, Frankfurt am Main.

- CHüRE, ALLAN N. (2003): On the neurobiology of attachment between mother and child. In: Heidi Keller (ed.): Handbuch der Kleinkindforschung. 3rd, corrected, revised and expanded ed. Bern: Hans Huber.

- Schröder, Achim (2017): Emotionalization of politics and authoritarianism.

- Challenges for contemporary political education. Available at: 2017, https://transfer-politische-bildung.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Fotos/Dossiers/Schroeder_Achim-Emotionalisierung_der_Politik_Vortrag_22-06-17_Weimar.pdf (18.04.2018)

- Spitz, René A. (1970): No and Yes. The origins of human communication, Stuttgart.

- Spitz, René A. (1976): On dialog. Stuttgart.

- Steffens, Jan (2016): Mental development paths between inclusion and exclusion. In: Professional Association of Curative Education Nurses in Germany (ed.): HEP Information. 38th year 3/2016. Krumbach. 33-40.

- Von Unger, Hella (2014): Participatory research - Introduction to research practice, Wiesbaden.