Teaching Portraits

In our (e-mail) interview series "Teaching portraits" , we talk to dedicated lecturers and winners of the E-Learning Schmuckstück competition in more detail about their ideas on teaching and e-learning as well as their personal lessons learned in the past semesters.

In the following teaching portrait, we talk to Dr. Markus Wutzler from the Chair of Computer Networks. His teaching was chosen as one of the winners of the "TUD E-Learning Gem" 2021 competition.

Further and current teaching portraits can be found at the bottom of this page.

How long have you been teaching at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

I have been involved in teaching at the Chair of Computer Networks since the summer semester of 2018 and took over a compulsory course for computer science teachers in the winter semester of 2018/2019.

For me, teaching means passing on knowledge and developing it further. That sounds very dry, of course, but I've often found that I was very interested in a topic, but didn't know where to start to find out more about it. When you decide to study, you may have very clear ideas about the degree program in question or simply a serious interest, but little knowledge. In cases of doubt, you may even have both, because during your studies you discover that the subject area is much broader or completely different to what you initially thought.

Ultimately, however, it is crucial that you have an interest and curiosity, because that is a great way to work. I enjoy getting students to understand our subject area independently or with a little help - it's often much more logical than most people initially imagine. This experience of competence, i.e. the "aha effect", often strengthens the students' own motivation to dig deeper and engage more with the subject.

How did you manage the switch from face-to-face to online teaching?

At the start of the 2020 summer semester, nobody knew how the exams would work that semester.

semester would take place. My motivation was very simple: I wanted to give all students the best possible opportunity to prepare for the exam - whatever it might be - at the end of the semester. To put it another way: the digital implementation should not serve as an excuse for not being able to take the exam. While our lectures have always been recorded, the exercise was previously only designed for face-to-face teaching. I saw the summer semester as an opportunity to digitize the entire exercise interactively and thus make it more widely available for the future, for example to be able to implement blended learning or flipped classroom. The effort involved was enormous: numerous OPAL tests for learning and self-monitoring were designed; exercises could now be submitted and had to be

exercises could now be submitted but had to be checked; synchronous exercises via BigBlueButton were established; a forum and a chat wanted to be managed.

In the winter semester 2020/2021, the same was done again for my own course. I was able to benefit from the preparatory work, but this lecture had not yet been recorded. In addition, a practical exercise that was otherwise carried out in the PC pools had to be moved to the digital room in winter. All in all, it was a huge time commitment, but the students generally always had positive feedback for the implementation, even if some were initially overwhelmed. I then took them by the virtual hand, symbolically showed them the way through the course and in the end most of them were very satisfied.

What are the positive aspects or limitations of online

teaching for your courses?

I see the asynchronous components (OPAL tests, videos, etc.) in particular as positive added value for the students, but also for myself. Students can organize their own learning time better, can also check themselves and then ask questions in a more targeted manner so that they can deepen their understanding better. Even in synchronous courses, everyone has the opportunity to participate.

One disadvantage is student participation. Even the umpteenth further training course, which showed me the y-th method for activating the students, no longer has any effect at some point. In this respect, the digital events became increasingly monotonous over the semesters. I am therefore looking forward to working on the practical aspects in person again, and I have to say that the internship in the digital space I mentioned earlier went unexpectedly well and smoothly.

Nevertheless, the activity of the students also suffers because everything had to be worked on in almost the same way. I hope that students will be able to work at their own pace again in face-to-face classes. However, traditional lectures can also be held on video in the future, as this time can be used much better with the students.

What do you think motivates students the most?

Looking back, I would say: commitment (of the lecturers) to good, varied teaching; an open ear for the students' concerns and the willingness to tailor their own course to the students' wishes/needs; transparency: why is the course the way it is?

A concrete example from my course in the winter semester: the students are asked to register for an exercise group. There are two exercise groups: one deals more with everyday working life (school), the other looks a little further afield. Before enrolling, I explain to the students very clearly what they can expect in the respective group. I also explain what the students can expect from the exam. As a

As a result, students register for one (or no) exercise group.

As a result, everyone goes their own way to prepare for the exam and I only have motivated

motivated students in the respective groups.

And is there anything you would recommend to your colleagues with regard to

digital teaching?

That is very individual. In our immediate environment, we are always discussing new approaches or things that didn't work out as we had hoped. In general, I think you should always try something new, but you shouldn't bend over backwards. I don't use methods (or their concrete implementation) that I can't take seriously myself. Otherwise, I try to transform what I do in person into the digital space. That rarely works 1:1. I usually think about what effect I want to achieve with the students and then try to find the right tool for that.

We would like to thank Dr. Wutzler very much for the interview and look forward to the further development of his (digital) teaching.

Further teaching portraits

Dr.-Ing. Iris Vogt won the E-Learning Schmuckstück 2024 in the category "31 to 100 students" with her course "Structural Design of Existing Buildings".

How long have you been teaching at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

I've been at TU Dresden for quite a long time, since 1998. I started out with no teaching experience at all, doing exercises and substituting for lectures. Over time, I was able to take part in a number of further training courses and develop my teaching skills. I remember one training course where I was asked about my experiences of lectures during my own studies. This question made me realize that nothing of the lectures I had attended had stuck with me and that I had done a lot of follow-up work. This solidified my desire to do better. I want students to be able to remember their own content even after the exam (and preferably even after graduation) and not forget everything straight away. It has to be worth it for me to give lectures at 7:30 a.m. in the winter semester! I think that a good education for our young people, from kindergarten to university, is important. Giving our students a good education should be the most important thing for us as a university. They are the most important potential for our future.

What are the positive aspects or limitations of online teaching for your courses?

Positive aspects:

- I enjoy trying out new things when teaching.

- Both the students and I can be creative when preparing documents and creating materials.

- You can try out different ways of teaching and learning.

- Distance learning students can "join in" - otherwise they often fall behind in normal face-to-face teaching.

- Lectures are not canceled due to illness; even students who are ill can follow up on lectures with videos.

- Many of the digital materials enable barrier-free learning.

- Most of the digital materials can be reused, either in subsequent semesters or in other courses.

- The playful possibilities of digital elements in particular loosen up learning for students.

Limitations:

- Creating new teaching materials takes time.

- Not everything works out as planned.

- Too much study material is confusing for students; you have to prioritize here.

- Students need time to work through the additional material.

How did you develop the e-learning approach in your courses and what role did student feedback play in this?

We started in 2019 (even before corona) with a project from the distance learning working group. As part of this, we acquired the initial basics of OER and CC licenses at the Institute of Building Construction and developed the first online materials. These are animations on building constructions that I still like to use for teaching the construction of existing buildings. Over the years, we have developed further materials and made them available to our students (direct and distance learning students). However, there were so many digital elements that it was rather confusing for the students and simply too much input. The idea was then to combine the most important materials into a kind of digital scavenger hunt. This is how the gamified OPAL course "LevelUp Bauko" was created, which is constantly being developed further. Feedback from students and thus the constant improvement of my teaching is very important to me. I want to offer students exciting and sustainable teaching and am happy to take on board suggestions for improvement or ideas from students. This gives me ideas for further materials or projects. For example, the idea for the Bauko-Caching project (funded by DLL) came about as a result of students' requests for excursions.

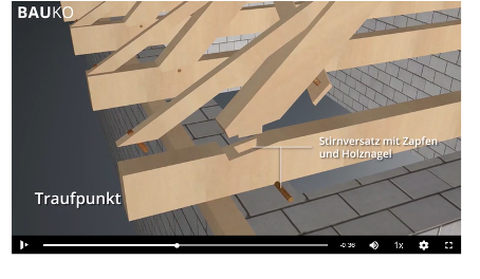

Startseite OPAL-Kurs

Auszug aus einer Online-Lektion von BAUKO

What do you think motivates the students the most?

A lecturer must be enthusiastic about their subject area. The spark jumps over!

Is there anything you would recommend to your colleagues with regard to digital teaching?

Just give it a try! Start small, for example with audience response systems like TUD.vote. Not everything has to be perfect, you can refine and improve it later. You also don't have to create OER material right away, but can first make something available to a smaller group size in the OPAL course. The majority of students are very grateful for break-up units in teaching, digital elements in lectures and documents that go beyond the traditional script. Nobody expects perfection.

The digital teaching teams of the departments offer networking meetings (e.g. School of Civil and Environmental Engineering), personal exchange and impulses for digital teaching. They can provide low-threshold advice, good starting points and help with implementation. Simply take advantage of the support. I can particularly recommend the networking meetings. You don't just learn about "digital" successes there, but also about how to deal with all the problems that arise. You realize that you're not the only one who doesn't succeed with everything straight away and that you can also create good e-learning elements with small steps.

Prof. h.c. Dr. Barth won the E-Learning Schmuckstück 2024 in the "over 100 students" category with your course "Latin-Greek terminology for medical and dental students".

How long have you been lecturing at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

I have been working as a lecturer at TU Dresden for 40 years. I have been teaching living foreign languages for 81 semesters and Latin-Greek medical terminology for 35 years. For me, teaching is the top priority in my work at the university. I have experience with more than 15000 students from the Departments of Medicine, Dentistry, Biomedical Engineering, Health Education, Biology, Midwifery, which I have already taught digitally. Personally, I am delighted with the successful teaching of material, I am still developing new teaching methods and approaches and am always striving to increase the efficiency of teaching. This variety of tasks can be realized particularly well digitally.

What are the positive aspects or limitations of online teaching for your courses?

For the living foreign languages, online teaching cannot be used for all language activities (placement tests, grammar exercises, reading comprehension etc. are of course possible). In Greek-Lat. Terminology, the positive aspects predominate. Firstly, little changes in terms of content and secondly, no communicative text knowledge is tested, but specialist terminology that can be practiced and tested online without any problems. Students can consolidate their knowledge individually at their own pace, receive immediate feedback on the solutions, can deepen or omit material and see their exam results immediately in the online exams. This enables more individualized learning. One disadvantage is the constant monitoring of security (preventing screenshots, photography, copying, copying of individual tasks).

How did you develop the e-learning approach in your courses and what role did student feedback play in this?

Back in 1997, I was one of the first foreign language teachers at the TUD to develop online programs and use them in my teaching. This was due to capacity reasons such as a reduction in the number of compulsory semester hours for the courses, but not in the teaching material, and constantly growing student numbers from 30 (1990) to around 500 today in 4 different departments, while the number of posts remained the same. All users of the program were professionally surveyed in writing over many years and the ideas and criticisms were immediately incorporated.

What do you think motivates the students the most?

Firstly, students are motivated by the variety of tasks that are possible in the moodle program as well as the independence in terms of time and location, the efficiency of learning, the possibility of mock exams and the prompt exam results. Without the online program, it used to take 6-8 weeks to correct exams.

And is there anything you would recommend to your colleagues with regard to digital teaching?

Digital teaching has become an integral part of university teaching. I would recommend not using it exclusively, but integrating it as an important element in the hybrid teaching process. In my subjects, the foundations are laid in lectures and seminars and the material is consolidated digitally through self-study without the need for supervision. Repeated independent practice has significantly improved performance, which in turn saves time for the examiner.creating digital teaching programs was a joint task. I would like to express my sincere thanks to my SHK/WHK, who have reliably supported me over the years.

Dr. Haase received the E-Learning Jewel 2023 in the category "31 to 100 students" for the lecture series "Bio-image analysis, biostatistics, programming and machine learning for computational biology".

How long have you been teaching at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

I taught at TU Dresden from 2019-2023. I wasn't even employed there at first. As a post-doc at the Max Planck Institute CBG in Dresden Johannstadt, I realized that many scientists on the Bio-Medical Campus had practically no basic knowledge of biomedical image analysis and machine learning. This made my work as a data analysis specialist in numerous collaborations difficult. So I decided to offer a lecture and found two great supporters in Prof. Michael Schroeder and later also Dr. Anna Poetsch. A few years later, I noticed that more and more doctoral students were coming to us with basic knowledge, also referring to the lecture, e.g: "I learned X from you back then and now I want to do X* with my data." This made collaborations much more efficient. Today, I work as a lecturer and training coordinator at the Center for Scalable Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence Dresden/Leipzig (ScaDS.AI) and here, too, we use online teaching formats [1, 2] to build interdisciplinary collaborations. For me, teaching is the best way to establish interdisciplinary projects and realize them in a goal-oriented way, because mutual understanding is the basis of every good collaboration.

What are the positive aspects or limitations of online teaching for your courses?

When I started sharing lectures on YouTube in 2020 due to the pandemic [3], this was of course an exciting new format for many people, which suddenly gave us a much wider reach. To date, my videos have been clicked on around 170000 times, and certainly not only by the 40 or so students who attended the virtual discussion groups. The idea of the flipped classroom was also new to me and I think the students really enjoyed watching the lecture on-demand, i.e. not in the rigid grid of a timetable. Discussing course content in Zoom meetings gave some students the anonymity they needed to ask questions that they would otherwise not have dared to ask. Unfortunately, others turned away and fell silent. I can't back it up with figures, but I suspect that the students who tended to do well anyway tended to get better grades through virtual teaching because they knew how to use the format to their advantage. The students who already had difficulties with learning did not all benefit from the new format.

How did you develop the e-learning approach in your courses and what role did student feedback play in this?

Initially, in 2020, my lecture was a classic flipped classroom. The students had a week to watch the lecture on YouTube and then we had an online discussion as a virtual meeting. There was an Etherpad, i.e. a document in which everyone could ask questions anonymously, which I then addressed in the next discussion. This form of teaching seemed just right to me at the time to take the pressure off the system. Back then, students sat in front of their computers for 8 hours a day and had Zoom meetings with their lecturers. They could watch my lecture whenever they wanted. To my surprise, the feedback from the students was that they would have liked to ask questions during the lecture and not a week later. So I rowed back in 2021 in terms of teaching concept, then together with my co-lecturer Dr. Anna Poetsch and also as a collaboration with Charles University Prague. We offered the lecture virtually at both universities, traditionally frontal teaching and subsequent discussion. Over the years, I have also gained very good experience with other formats such as group work and lectures in virtual meeting rooms that feel like computer games [4].

Avatare von Studierenden auf Online-Plattform

Today I combine formats as required. I think that groups that have met several times in person benefit more from virtual teaching formats than groups that have never been in the same room. This is probably due to the fear of asking a "stupid" question in an unfamiliar group. Tip: Call yourself "Ann Nonym", leave your camera out and just start asking questions.

What do you think motivates the students the most?

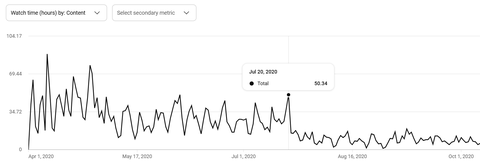

Students seem to be more motivated the further away they come to us virtually. This is obviously more relevant in training courses that are offered beyond the university. I work in the Global Bio Image Analysis Society with colleagues from all over the world on virtual training courses [5] and the community naturally loves having quasi-global access to expert knowledge. For local students, it is probably more interesting to be able to watch lectures again at any time. In 2020, I registered a small peak in the watch time statistics on YouTube - the day before the exam. Whether this last-minute re-watching of videos contributes to efficient learning remains to be seen.

Watch Time Statistik Youtube Kanal

And is there anything you would recommend to your colleagues in terms of digital teaching?

Take advantage of the opportunities offered by the digital age and share your knowledge online. Be it as a lecture on YouTube, lecture slides on Zenodo.org or sample code and exercises on Github.com. There is certainly no shortage of platforms for sharing materials. This is good for students worldwide, good for the visibility of the university and certainly also for yourself. In addition, there is unfortunately still a lack of high-quality, reusable training materials in some disciplines [6]. If we all shared more knowledge and materials, it would be easier for the next generation of lecturers to put together good course materials. Unfortunately, we are the first generation to have to deal with the challenges of FAIR sharing [7], because the generations before us invented the internet. If sharing material seems like a big challenge to you, you are not alone. Contact the colleagues at ZiLL [8] and contact your subject-specific NFDI [9] - the National Research Data Infrastructure is also in the process of transforming training and teaching materials into the digital age and will be happy to support you.

Sources:

[1] https://scads.ai/transfer/teaching-and-training/

[2] https://www.youtube.com/@scads-ai

[3] https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL5ESQNfM5lc7SAMstEu082ivW4BDMvd0U

[4] https://github.com/haesleinhuepf/I2K2022-napari-workshop

[5] https://www.youtube.com/@globias

[6] https://osf.io/preprints/osf/2zgmc

[7] https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata201618

Maximilian Vogt and Daniel Haak received the prize for the E-Learning Jewel 2023 in the category "over 100 students" for "DVR - Dresdner Vorklinik Repetitorien".

How long have you been teaching at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

The voluntary work in our working group is characterized by constant fluctuation. We both joined the project as a tandem at the end of 2020, after completing our 1st state examination (Physikum). We managed the DVR until the summer semester of 2024 and handed over all organizational tasks to the next generation when we entered our final year of study, the practical year (PJ).

For us, teaching is the art of recognizing where I can pick up my counterpart's level of knowledge and what opportunities I can then offer to expand it or consolidate it in application. At the same time, teaching is also a development process for the teacher, which is why you can consolidate your own knowledge by explaining and repeating it during the teaching process. For us students of human medicine in particular, the basic sciences are not anchored in the curriculum with the completion of the first state examination, but the DVR gives us the opportunity to recall the basics again in higher semesters and use them to develop a better understanding in the clinic.

Einblick in DVR OPAL-Kurs

What are the positive aspects or limitations of online teaching for your courses?

A major advantage of online teaching is that the content is available anywhere and at any time, which allows students to use it flexibly. OPAL, our teaching management system, allows us to prepare our content in a variety of ways to suit every type of learner. Be it interactive drag & drop tasks, crossword puzzles, point and clicks or a round of memory with biochemical formulas, the possibilities here are limited only by your own imagination. The biggest disadvantage, however, is the limited feedback, which is essential in the teaching process and is greatly weakened by distance.

How did you develop the e-learning approach in your courses and what role did student feedback play in this?

Originally, our online course arose from the need to be able to continue offering students exam preparation revision sessions from home despite the lockdown. We started by uploading pre-recorded videos of our lectures and shortly afterwards recognized the real potential of such online teaching management systems and created our self-tests in the process. In addition to face-to-face events, we offer students the opportunity to reuse and interactively internalize learning content for later state examinations. Unfortunately, feedback is often limited in asynchronous formats, but we consistently take the feedback we receive into account when further developing our materials.

What motivates students the most?

Students are most motivated when they find well-thought-out and comprehensive teaching materials and feel that the teachers are making an effort to explain the content clearly - until all open questions have been clarified. However, a clear structure and a consistent approach that separates the essential from the non-essential is particularly important. Particularly with regard to revision courses in preparation for exams, a common thread must be drawn that links the content in a didactically clean way, but does not get lost in detail and runs stringently through the course in order to generate maximum benefit for the students.

What do you recommend to your colleagues with regard to digital teaching?

We recommend making digital formats as interactive as possible and clearly communicating to students that feedback and questions are expressly welcome. To strengthen the feedback culture in particular, it is important to show students that feedback is heard and has relevance. Comparisons from previous courses and explanations as to why there have been changes here or there create more transparency and give students the feeling that they can really change something with their feedback. At the same time, you should be prepared to try out new approaches and continue to develop yourself. A well-thought-out mix of asynchronous teaching and live interactions can combine the best of both worlds.

Mr. Dutsch won the E-Learning Schmuckstück 2022 in the 31-100 students category with "Operational processes and operational planning in public transport".

HD: Mr. Dutsch, how long have you been teaching at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

SD: I've been at TU Dresden since the Faculty of Transportation Sciences was founded in 1992 and was already working at the University of Transport before that. When I started there in March 1986, I was immediately asked to give lectures. My very first seminars were exercises on wagon running plans, which I was asked to take over immediately after starting work. These were characterized by a large amount of material. Since then, I have been teaching continuously. The number of exercises and seminars grew quickly, with the departure of my first professor the lecture series was added and after the departure of his successor a few years ago there was even more. I really enjoy teaching. It is a very important activity for me and the university to pass on knowledge and train capable young people.

HD: What did you particularly enjoy about planning and implementing your teaching concept?

SD: It was the opportunity and at the same time the necessity to rethink, systematize and modernize the entire subject matter. I put a lot of thought into the lectures: What do I choose in lectures and exercises? What are new things, what are old things that need to be replaced? And of course the question: How do I present it clearly and comprehensibly? This question was particularly important during the exercises when I was making instructional videos and self-tests.

HD: What are the positive aspects or limitations of digital teaching for your courses?

SD: I'll start with the limitations and name them honestly: my lectures and exercises also rely on many practical examples. When I started creating teaching videos, especially during the coronavirus pandemic, I had to forego some of the digital teaching out of consideration for those involved in the practical companies. I became aware of this as a limitation. You can only get some things across if you are in the same room as the students. It's a significant limitation. Another is the interaction with students, which requires more time. It's difficult to get immediate feedback when you're not present in a forum or by email.

One advantage is that you can use the digital tools - videos, self-tests, PowerPoint slides - multiple times. To my astonishment, many issues were understood just as well or perhaps even better. I explain this by the fact that, on the one hand, I have given didactic thought to presenting things in teaching videos in a particularly understandable way and, on the other hand, there is the option of looking at difficult things several times. Previously, if I wrote something on the board and a student wasn't present or was distracted, they didn't catch it. Now they can watch it again in the video and catch up.

Another effect is that, as a teacher, you are more precise on a video, both graphically and verbally. If something didn't work perfectly when you were creating it, you usually go back and correct the mistake and repeat it again. I was surprised by the quality of the students: Even during Corona, I couldn't really tell that the students were worse than usual, not even later in coursework or dissertations. So the concept worked.

Today you have to weigh things up: In the lecture hall I have direct contact with the listeners, with a video I have the opportunity to present things in a more concentrated and precise way in pictures and words. And there is clearly the positive effect that students who were unable to attend a tutorial or lecture can simply work through things with videos and self-tests in self-study without having to rely on the notes of other fellow students. And I can now offer several equally valid solutions to the same problem: some on video, others in the classroom.

HD: What do you think motivates the students the most?

SD: First of all, of course, the subject. It's practical and popular, it leads to high attendance rates and a high take-up of electives. And then the lively presentation of the material with examples. The many examples make it clear to students what they need to pay attention to later. That's why I've always tried to give lots of examples in the classroom teaching and I've also incorporated this into the videos as far as possible.

HD: And is there anything you would recommend to your colleagues in terms of digital teaching?

SD: You simply have to try out what goes down well with the students. While the self-tests were very popular at the beginning, they are being used less again. Now we also offer the exercises as videos. Now that a lot has changed in the lectures, we no longer make the teaching videos available because we haven't managed to keep up with the word. Instead, we have informative slide sets. The students now have a whole portfolio of products. And: the aforementioned leap in the quality of the content, which was created by recording the teaching videos, is now leading backwards to an improvement in the face-to-face courses.

HD: Thank you very much for the interview.

In the following teaching portrait, we sit down with Dr. Christine Andrä from the Chair of Political Science. Her teaching earned her the teaching award of the Association of Friends and Sponsors of TU Dresden. The interview is available in text (see below) and as a podcast.

“A great amount of creativity and interactivity as well as an open and participatory atmosphere” is how the Institute of Political Science describes the seminar of the recently selected winner of the teaching award given out by the Association of Friends and Sponsors of TU Dresden. Furthermore, the website of the Institute of Political Science reads: “She manages to fill the Zoom room with life and stimulating discussion despite the forced move to online teaching thanks to her engaging and open-minded nature.” The following interview between Dr. Christine Andrä and Dr. Ingo Blaich from the Digital Teaching Team at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences gives insight into exactly how Dr. Andrä achieved this and what specific adaptations digital teaching entails. Enjoy!

IB: Ms. Andrä, you received the teaching award of the Association of Friends and Sponsors of TU Dresden in the 2021/22 winter semester and we are very pleased that you are available for an interview with the Digital Teaching Team. The first thing we want to know, of course, is: For which course were you awarded this prize and what was the special didactic feature of that course?

CÄ: Thank you very much for inviting me to this interview. I was incredibly happy to receive this teaching award. This is a great award, also for the whole team behind the course. I will say something more about that in a moment. The course was a preliminary seminar called “Introduction to the Study of International Relations,” primarily for students in the 2nd semester of their Bachelor’s degree program, though there were a few who came from other degree programs and took the preliminary seminar in higher semesters. But, the majority of the students were from the 2nd semester of political science in the different programs we have there, for instance the Bachelor’s in Teacher Training or Bachelor’s of International Relations. This was a big seminar. I double-checked: 100 students were enrolled. Not all of them joined every Zoom session, of course. We had weekly Zoom sessions that were full every time. The preliminary seminar took place within the framework of a fundamental module that we have in political science, namely the fundamental module of international relations. There is also a lecture and a tutorial. There are several preliminary seminars running parallel to each other, one of which I gave. The content of this fundamental module and especially of the preliminary seminar focuses in particular on the theoretical foundations of international relations. In the preliminary seminar, we do a lot of work with texts to introduce students to scholarly texts in our field for the first time.

The special feature in the didactic implementation was that in my preliminary seminar and in the other preliminary seminars there were fixed small groups of 5–7 students each, who met repeatedly week after week for a portion of the seminar. The seminar started with us greeting each other and then I asked if there were any questions, comments or concerns to start with. Then, it was straight into the small groups, where students met increasingly familiar faces throughout the semester. Students were also always given leading prompts in advance about the texts they were supposed to have read. These were first discussed in the small groups and then discussed in the plenary. I went through the breakout sessions during the small group work, of course, and looked to see how things were going and what the snags were. To a certain degree, this was supposed to serve the discussion of content, and it worked quite well. I suspect that many of us faculty experienced sometimes silent, not particularly discussion-friendly events during the pandemic. Many students tell me that they are more inhibited when sitting in front of screens, as they don’t know who the others are behind those tiles – even if they have a picture visible, which many do not. And in the small group work, it was clear that everyone needed to get involved on a regular basis. It was felt to be a more conducive space for discussion. So, the discussions afterwards went much more smoothly. At the same time, I think it was very important for students in the early semesters to get to know each other because of the social aspect. Unfortunately, this doesn’t take priority in the times of Zoom. Many students did not move to Dresden at all. This is a generation of students who didn’t start studying until after the pandemic began. I think a lot of people liked that. I also found it nice to gradually witness the dynamics in small groups. We also had a brief welcome moment in each session, with a breakout feature on Zoom where I would randomly send two students into a breakout session together for two to three minutes. Here, two students always said hello to each other, as one would ultimately do when walking into the seminar classroom.

This seminar was flanked in the module by the lecture and tutorial content. And that is why the teaching award is also an award for the entire team of this basic module. There were a total of ten of us, including the tutors who managed it. So, there is a coordination effort as well, which was done through Zoom. The arrangements were virtual during the summer semester.

IB: That means, your seminar was thematically linked to the lecture and tutorials, so that a common thematic bracket was created?

CÄ: Exactly. So that in the seminar, and in the tutorials that took place as well, I also responded to questions about the lecture content when they arose. It was envisaged that the lecture would lay a foundation of content. Then, the students read texts in preparation for the seminar, which we then discussed. And in the tutorials, techniques of scientific work were practiced and empirical case studies were played out. That was the linking element.

IB: What differences do you see in the preparation and design of courses between digital teaching and in-person teaching after several semesters of predominantly digital teaching? Is this still clearly visible? Are there any habituation effects, or do significant differences remain even after two years?

CÄ: I believe both. I think that many of my teaching principles, which are fundamentally important to me, apply just as much to digital teaching as they do to classroom teaching. Regarding the differences: I remember my first online semester, which was also my very first semester at TU Dresden. I was in the same boat as many students. I only started working in Dresden during the pandemic. Before my very first semester, I was in an experimental mood and thought up all sorts of things out of the blue because I had no experience at all. After all, that’s how most of us felt. By now it’s a little more routine, as you said.

And there are a few points that I now know I need to consider in particular. First of all, as already mentioned in the description of this seminar, I have to plan more time for social activities and interaction and explicit methods and tools to this end. I have to make this explicit as an element that belongs to a course or seminar. That doesn’t just happen on the side, like you have with in-person teaching, especially in seminars, maybe less so in lectures. Second, I think online teaching is demanding in a different way. Students tell me this very often. Of course, because of the enormous amount of screen time, but above all because it requires a great deal of self-organization and self-motivation from the students. We sometimes underestimate this because it is essentially invisible to us. Until we ask about it or someone tells us. I think I have to somehow account for this extra effort in the planning and in the design. In particular, which content I structure as well as which methods I use and how I apply them. And the third thing is – although I don’t know if that’s just my experience or if it’s shared more broadly: I have observed that in online teaching, depth of content is easier to achieve or implement than breadth of content. Of course, this sometimes clashes with seminar objectives. When I have an introductory event, I just want to go broad. Sometimes that’s not so easy. I think that these are simply advantages and disadvantages that we have had to live with, particularly during the pandemic, and make the best of. After all, achieving depth instead is not a bad thing. But it’s also good if we can mix online and in-person formats a bit more in the future.

IB: What could be the reason that depth is easier to achieve and breadth more difficult? In traditional classroom teaching, it’s rather the other way around: That is, it’s easier to take a look here and there and it’s more difficult to deal with a topic in depth.

CÄ: I’m not sure. I think it might be because of the different social dynamics, among other things. No matter what methods we come up with, everyone is a little less spontaneous and inevitably more focused in the exchange. With virtual methods, I can simply demand and promote a deep, focused discussion of a single point more effectively. And I think it might be, again, the point of self-organization: Students are less able to survey the breadth of the subject and content, especially at the beginning of their studies. And the more teaching has to rely on self-organization, the more difficult it therefore becomes to achieve this breadth of content. But I would actually be interested to know if there are any studies on this. Someone will certainly have already addressed this from a scientific perspective. Above all, whether this can be observed in general and what the reason is for this.

IB: This is precisely what will certainly be the subject of future reappraisal and further development of teaching against the background of the pandemic experience, in order to be able to benefit from it for further university teaching. Finally, one more question. In general: What do you enjoy about online teaching and where would you see future challenges for yourself, especially in the further use of digital teaching elements?

CÄ: I love teaching because I can accompany my students a little bit as they learn and because I am always thrilled when moments of learning together succeed, for instance in project work, when the students’ creativity really comes out. That’s where I’ve had a lot of great moments in online teaching over the past few semesters. Not in the seminar we just talked about, but in more advanced seminars. Students recorded podcasts themselves, populated Instagram channels on our seminar topics, designed padlets and blogs, and overall contributed enormously. And they did a great job of interweaving the content with different forms that they came up with themselves. To guide and accompany something like this is a lot of fun for me.

Among the challenges: I would very much like to take the good from online teaching if we go back to more in-person teaching or if we can mix in-person and online teaching more and more flexibly in the future. Before the pandemic, we probably all had very set ideas about what a seminar was and what a seminar session was, including from our own study experiences. This has inevitably become somewhat more flexible. And opened up room for maneuvering. By no means were we necessarily asked for this creative room to maneuver, but there was a lot of room to try out and experiment. I would like to continue doing that and also maintain the joy of it. What I generally found challenging in online teaching, even more so than with in-person teaching, was not losing students. Unfortunately, despite all efforts, this has happened and continues to happen again and again. And that’s where you have to stay on the ball as much as possible. If I notice that someone is no longer coming or seems to have logged off, then I also ask. Of course, that doesn’t always work out, especially in very large courses, because I can’t always keep track of everyone. I hope this will be a little easier now in person or partially in person. Because it’s already something different and conducive to all kinds of things when we meet in person – as great as it is now that we have Zoom or BigBlueButton or all these other tools – it’s still something different. So, given that challenge, I’m quite hopeful that we’re all now headed into a somewhat easier summer term together, hopefully.

IB: That’s right, I think we all hope that. I’m curious to see how it turns out then.

CÄ: We all deserved it very much, too. The teachers, but especially the students. It took a lot out of them.

IB: We wish you all the best for the summer semester and all future semesters as well as more wonderful teaching success. Once again, congratulations from the Digital Teaching Team on your teaching award and thank you very much for this interview.

Dr. John Martinovic, Research Associate at the Institute of Numerical Mathematics, won an award for the “2021 gem of e-learning” in the category of “Courses with 31 to 100 students” for his lecture “Optimization – Basic Concepts.”

Dr. Martinovic – How long have you been lecturing at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

Apart from minor episodes as a student assistant during my own studies, I have been teaching in the classical sense at TU Dresden since 2015. At that time, I was in the early phase of my doctorate in a third party-funded project, the continuation of which was not yet certain. Fortunately, another institute needed a substitute in the middle of the semester to maintain certain teaching duties, so that through this “detour” I was not only able to gain initial experience in leading exercise groups, but also to place my doctorate on a more solid foundation (in financial and planning terms). Since then, I have been continuously involved in teaching and have worked there as a training supervisor, course assistant and lecturer, in particular in mathematics education for the courses of mechanical engineering, traffic engineering, chemistry and computer science, as well as being responsible for some optimization lectures for mathematics and the teaching profession.

For me, teaching is the most significant component within the canon of academic tasks. Good teaching is the indirect starting point of all university action, since it first helps students to master the sometimes difficult transition from school to university, and at the same time encourages them to deal with the topics covered themselves, possibly even to become enthusiastic about applying them later in a social context or to contribute to the second elementary pillar of any university operation within the framework of their own research work. Nevertheless, I have the feeling that in hiring or appointment procedures, research activities are given first priority, while teaching experience and success are treated as secondary. I have no delusion that this weighting will change in the near future, but I would like to see a more balanced appreciation of both areas of work overall, as this is an important basis for long-term quality assurance in the area of teaching.

How did you manage the switch from on-site to online teaching?

To be honest, not well at all. Especially at the beginning, when the university closed its doors for an unforeseeable period of time, you were largely left to your own devices in dealing with the challenges that came with it. This is not meant as an accusation, because no one really knew what was coming or how long the pandemic would ultimately accompany our lives. Nobody was really prepared, neither technically nor methodologically. My first steps in online teaching (for mathematics exercises), which from today’s point of view are not very sophisticated, were consequently limited to providing detailed solutions and being “available” for questions in chat rooms or video conferences. As expected, this was not particularly well received!

It was not until the following months, when the personal exchange among colleagues, but also the support offered by the university, e.g. in the area of tutorials and software licenses, steadily increased, that I gradually succeeded in offering a decent alternative to classroom teaching. It was certainly also helpful that I was appointed as a substitute professor for the duration of a semester and thus had to independently take responsibility for more important teaching tasks. On the one hand, this was a personal incentive; on the other, it offered sufficient opportunities to develop in the right direction, true to the idea of “learning by doing.”

What are the positive aspects and the limitations of online teaching for your courses?

I think it is imperative to answer this question from the perspective of the students, since they have had to bear the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic in the university context. We lecturers had to deal with all kinds of inconveniences during the transition to digital teaching, but in most cases we did not face any existential challenges. On the contrary: Providing asynchronous lectures and holding courses not in one singular location has made the otherwise very regular, in-person and deadline-oriented work during a normal semester more flexible in many places, and certainly not to personal disadvantage.

However, I myself teach in a subject area that thrives on interaction in the lecture hall. Mathematics still works largely with blackboard-and-chalk and question-and-answer format. Ideally, solution ideas and derivations should be discussed and developed together systematically. This is difficult from a distance. In this respect, I think that online teaching in mathematics has been immensely challenging for many students, especially in teaching export. I therefore have great respect for all those who had to overcome difficulties in understanding and motivation largely on their own during this phase and were able to make progress in their studies despite unfamiliar conditions.

If I had to name a challenge for my personal work, I would mention the sensible design of alternative forms of examination. Mathematics examinations consist to a decent extent of conventional arithmetic problems; conducting oral examinations is rather unusual and not an option, especially in larger courses. So if you don’t want to fundamentally change the basic character of an exam, you have to take the risk that technical aids can be used relatively easily to find or check solutions, even though I don’t want to accuse anyone of doing this, of course. To this day, I have not found a proper and convincing solution to this problem.

What do you think motivates students the most?

I take a more rational and pragmatic approach, according to which many students already bring certain interests, expectations, and experiences to the university, which they document for instance through their chosen field of study. In certain cases, a teacher may be able to light a fire – but in mathematics, which is commonly (and not entirely unjustifiably) perceived as dry and theoretical, it is difficult to motivate someone against their inner convictions or personal feelings by means of vivid experiments or spectacular findings. For example, I often hear the guiding principle “the main thing is to pass!” – perhaps an understandable reaction to “self-fulfilling prophecies” of earlier cohorts, a majority consensus in society for the assessment of STEM disciplines, and the actual expectations of the field I represent. However, one should not make the mistake of interpreting this as factual disinterest. In many cases, a course of study simply demands that priorities be set; the motives for their concrete design can be quite different. I think that if you succeed in giving students the feeling that you are doing everything to accompany and support them on this sometimes arduous path, they will gladly reward you with their own motivation and cooperation, even if mathematics as such is not one of their closest friends.

And is there anything you would recommend to your colleagues in terms of digital teaching?

Admittedly, I don’t have a patent remedy and I don’t think that I have reinvented the wheel with my methods, so to speak. It depends, as so often in life, on good chemistry between the “sender” and “receiver.” This may develop for very different reasons or may not develop at all – in any case, the audience decides for themselves. In the end, the most important thing is to remain authentic, try not to pretend, and at best admit your weaknesses with humor. This also includes being aware at all times of one’s role as a translator of “technical language -> German,” thus communicating explanations in a manner appropriate to the addressee and, in some cases, stepping back behind one’s own claims to exactness for the sake of better comprehension. It was probably helpful that I only finished my own studies not too long ago and that I was therefore able to reconstruct quite well the concrete way in which I myself once found an approach to difficult topics.

We thank Dr. Martinovic very much for the interview and are looking forward to the further development of his (digital) teaching.

Prof. Melanie Humann, Chair of Urbanism and Design, won an award for the “E-Learning Gem 2021” in the category of “Lectures with more than one hundred students” with her digital implementation of the lecture “Urban Planning 1”.

- How long have you been lecturing at TU Dresden and what does teaching mean to you?

I joined TUD’s Institute of Urban Planning in 2018. I have been teaching for over eight years as a professor and before that as a research assistant at various universities in Germany.

We have highly individualized student support at the Faculty because of the urban architectural design teaching. Therefore, we try to provide special encouragement to our students to think and work very independently, creatively and conceptually. Of course, we also work hard to impart knowledge. But I am concerned with placing a very strong emphasis on independent thinking and conceptualization.

Due to the dynamic developments of our time, we can no longer rely solely on existing knowledge, but must permanently search for new ways, for example, to deal with the effects of the climate crisis or digitalization. It is of course helpful if you can not only reproduce knowledge, but also develop and design solutions independently.

It is important for me to have enough freedom in teaching – to try things out and fail. I often tell students, “If you’re going to fail, you’d better do it now and not in your professional life.” It’s important to get that experience while you’re still at university so you can acquire strategies for the job.

What does teaching mean to me overall? I believe that teaching consists of providing a Compass with which students can orient themselves well in their professional field – despite the presumably major changes in the framework conditions over the next decades.

- How did you manage the switch from in-person to online teaching?

That was a big challenge at first. I had to rely on the students to work on the documents I sent them. Therefore, we compiled very diverse teaching materials, for example excerpts from literature, links to videos and blogs or to planning offices – in other words, everything that motivates self-study. The teaching materials were more diverse than in my in-person lecture.

Online teaching has forced us to think harder about what materials are really appropriate for independent study, what open-source media are now available, and what communication formats students also enjoy. What are the new projects and platforms? What are some films that address the topic? This is how we cobbled together the “corona packets” – independent study packets that had to be “consumed” in a certain time. If some were a little more interested, they could also view additional materials and do research on them.

Overall, the transition has been a great learning process for us and the response from students has been positive. We will now take the lessons learned from purely online teaching into hybrid or in-person teaching, and continue to consider what formats and tools can be usefully employed post-pandemic.

- What are the positive aspects and limitations of online teaching for your courses?

We have had both positive and negative experiences. After four semesters, we have gained a pretty good overview of which of our teaching modules work well digitally and where new opportunities are even opening up as a result of the digital tools. For example, we have had very good experiences with the digital whiteboards, which strongly promote collaboration and knowledge transfer between students. We set up a digital whiteboard for all seminars, which students actively worked on throughout the semester. They could put their work and research in there, and the other students had access to the knowledge base that it created. The students also presented on the boards, and as the supervisor, I always knew the status of the work.

A nice side effect of the ad hoc changeover was also that students gave us more feedback on their own accord – for example, on the quality and delivery of videos, on their own digital capabilities, or on other topics that we often don’t even notice from the instructors’ perspective. Especially now, during the mixture of in-person and online teaching, many students have reported to us, for example, that they don’t even make it to the courses on time because they start the day studying at home and then have an on-site course. Through this feedback culture, teaching has once again been shaped quite actively by teachers and students together.

For the past three semesters, we have also hosted a biweekly digital Teatime Talk event, to which external guests were invited to give students brief input on a specific topic. Video conferencing tools have made it much easier to invite a large network of experts and to make their expertise directly, cheaply and easily available for teaching.

Moving on to the negative aspects... design teaching is not something we can do online. We tried everything, using iPads, pens and 3D models. This quick “I’ll push something back and forth in the models” or “I’ll draw a sketch, throw it away and draw a new one” just doesn’t work digitally, and personal contact is incredibly important at this point. That’s why we also did as much in-person teaching as possible – if it was possible according to the corona guidelines – and actually also had workshops lasting several days in a row. We rented larger halls in the city specially for this purpose.

- What do you think motivates students the most?

Above all, the exchange with each other. I have the impression that the current generation of students is no longer as competitively oriented. It is no longer about being the best, but rather about collaboration and knowledge sharing, finding common solutions to future problems, it is about the subject itself.

In recent years, the desire of students to work and engage intensively on societal issues such as climate change or the circular economy – either through research or real-world inquiries – has become apparent during their studies. Especially in our area, because we are very close to the issues of the living environment with construction and urban development. With teaching, we lay the groundwork for students to be able deal with these future topics at an early stage.

- Is there anything you would recommend to your colleagues in terms of digital teaching?

Just try it out and let the students try and co-design in the process. As I said, this is how we discovered that digital whiteboards work for us and now we wouldn’t want to do without them. I could imagine that this is a good option for many special fields and can be interesting in the long run. At its best, digital teaching should go beyond implementing “analog” teaching with digital tools.

We were mainly concerned with designing the framework for independent study in such an attractive way that students can also acquire their knowledge well in the online mode. But it also includes reflecting on the forms of examination and, in this context, realizing that some forms of examination are outdated – that they no longer fit in with our teaching or philosophy.

And what has become more important to me personally – or what I am more aware of is: the personal contact with the students. That simply cannot be replaced by any digital tool.

We would like to thank Prof. Humann very much for the interview and are looking forward to the further development of (digital) teaching at the chair.